Iberia

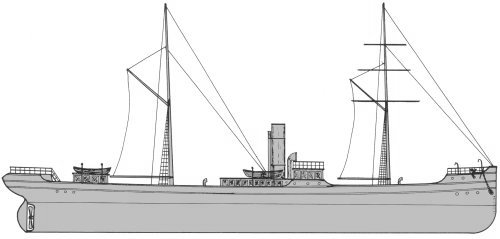

- Type:

- shipwreck, steamer, France

- Name:

- Iberia is Latin for Spain or the Spanish peninsula.

- Built:

- 1881, Scotland

- Specs:

- ( 255 x 36 ft ) 1388 gross tons, 30 crew

- Sunk:

- Saturday November 10, 1888

collision with liner Umbria ( 7798 tons) - no casualties - Depth:

- 60 ft

In a dense fog, 14 feet were sheared off the Iberia's stern by the Umbria. She sank the next day and was later partially salvaged.

This is a popular dive site because of its inshore location and easy depth. Visibility, however, tends to be poor, and can drop to zero if you or another diver are careless and stir up the silty bottom. Under such poor conditions, I pretty much just blundered around the wreck at first, following the southern edge from near the bow back. I didn't really get any impression that this was a ship until I reached the 3 1/2 bladed propeller. Then, turning around, it was easy to follow the propeller shaft up to the 25-foot tall engine, over the top of that and down onto the boilers, and eventually back up to the chain pile in the bow. The aft part of the wreck is linear, while the fore part is broken up and can be confusing.

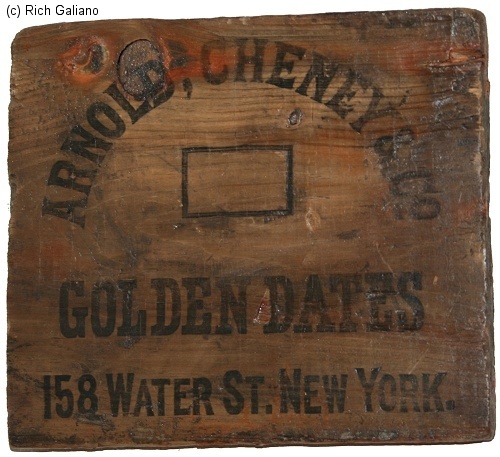

This wreck is known for the embossed crate boards that may be found by digging in the stern area. Otherwise, lobsters are few and the fish are small. There were a great many crabs - all dead, probably due to a low oxygen event, common in nearshore waters. Much of the wreckage, especially the higher areas, is covered with white hydroids and even some encrusting corals and might make a nice photo op on a clear day.

Iberia

The steel-hulled freighter Iberia was built in 1881 by S & H Morton & Co. in Leith, Scotland. She was owned by the Fabre Line and displaced 1,388 gross and 943 net tons. The Iberia was 255 feet long and had a 36-foot beam.

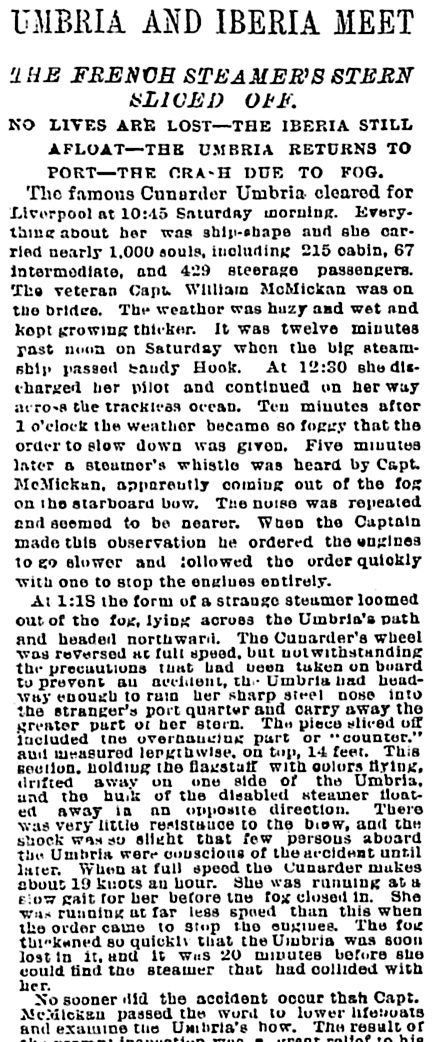

The Iberia, under the command of Captain Sagolis, was bound from the Persian Gulf to New York with a cargo of 28,000 crates of dates, a few bales of hides, and coffee, all consigned to Arnold & Cheney Inc. of New York. She developed engine trouble just a few miles off Long Island, New York where she lay at anchor for three weeks awaiting repairs. Once repairs were made she slowly started to make her way to New York. Meanwhile, on Saturday morning, November 10, 1888, the 520 foot long Cunard luxury liner Umbria, bound for Liverpool, encountered dense fog as she sailed out of New York harbor. The Umbria, which was under the command of Captain William McMickan, was sailing with 215 first-class passengers, 67 second-class, and 429 steerage class passengers. Captain McMickan reduced the Umbria's speed, posted a lookout, and began to blow the vessel's foghorn.

According to eyewitness accounts listed in a NEW YORK TIMES article "At 1:18 PM the form of a strange steamer loomed out of the fog, lying across the Umbria's path and headed northward. The Cunarder's wheel was reversed at full speed, but notwithstanding the precautions that had been taken on board to prevent an accident, the Umbria had headway enough to ram her sharp steel nose into the stranger's port quarter and carry away the greater part of her stern. The piece sliced off included the overhanging part or 'counter, ' and measured lengthwise on top, 14 feet". "This section holding the flagstaff with colors flying, drifted away on one side of the Umbria and the bulk of the disabled steamer floated away in an opposite direction".

Passengers aboard the Umbria later noted that there was very little resistance at the time of the collision and the shock was so slight that few persons aboard the Umbria were conscious of the accident at all. The NEW YORK TIMES also reported the Iberia's Captain Sagolis statements. "We were running only three knots an hour because of the fog and the noise of whistles all around. Our whistle was kept going at short intervals to warn approaching craft. When I first saw the Umbria she was alarmingly near to the Iberia. The collision seemed imminent, and my only hope was to escape a direct blow. The helm was put hard over, as it seemed that we were to be cut in two. The Iberia responded quickly and we nearly got clear of the Umbria's course. She cut through our stern with a crash and disappeared into the fog".

Back aboard the Umbria Captain McMickan passed the word to lower a lifeboat and inspect for any bow damage. The result of the inspection gave his mind great relief. His steamer had only been slightly damaged, but not seriously enough to endanger any lives. Soon after the inspection, the Umbria started to search for the Iberia. When the Umbria finally got within sight of the crippled Iberia, she was flying a flag of distress and had dispatched a small lifeboat. Both captains discussed the situation, with Captain McMickan recommending that all crew be transferred to his vessel. Captain Sagolis refused to desert his vessel. His opinion was that, with her six watertight compartments, she could be towed into port.

The two vessels laid at anchor until the next morning. Captain McMickan finally persuaded the Iberia's crew to board the Umbria before he steamed toward New York for repairs. Shortly after abandoning the Iberia a salvage crew from the pilot boat Cadwell H. Colt was put aboard. The crew of three remained aboard while the Cadell H. Colt rushed to retrieve two tugboats for the salvage operation. Later that afternoon, Sunday, November 11th, Captain Sagolis returned to the wreck site with the tugboats but found no trace of the Iberia. The salvage crew that had remained aboard claimed that a bulkhead had collapsed and the steamer began to fill rapidly. The crew barely had enough time to escape in their longboat before the Iberia went down.

According to an article in HARPERS WEEKLY dated December 8, 1888, after the collision, the Iberia had drifted a mile inland and now lies "on her beam ends, tilted over so far on her starboard side that the tips of her two masts are buried in the mud. The bottom is gravel, mud, and sand". The article also reports that salvage was considered and that the wreck site had been located by two Merritt Wrecking Company tugs by towing a three-and-a-half-inch diameter cable until the wreck was snagged.

Today, the Iberia sits in 60 feet of water, about 3 miles offshore and mid-way between Debs and Jones Inlets, Long Island, New York, in an area known as Wreck Valley. After spending 93 years in her final resting place on the ocean's floor her bulkheads and sides have broken down, a testament to the destructive power of the sea, leaving only low-lying ribs and wreckage scattered on the sandy bottom. Her bow section, boilers, engine, and steel propeller are all easily recognizable. Divers can still locate the remains of wood crates that once contained her cargo, or simply enjoy exploring the wreck, spearfishing or lobstering. To the best of my knowledge, no one has ever located the missing stern overhang section.

Excerpted from Wreck Valley CDROM by Dan Berg

Questions or Inquiries?

Just want to say Hello? Sign the .