Collision at Sea

How do two ships in the wide ocean collide? It seems unlikely, and yet it happens all the time. Often, the ocean is not all that wide. Many collisions occur in shipping lanes and port approaches, where ships are brought together in close proximity. Here are some videos of actual collisions between ships:

This video is actually boring. The two huge tankers approach each other at a snail's pace, and everyone is completely aware of what is happening. Yet, even before the beginning of the video, the collision is inevitable. Large ships are not maneuverable. Stopping distances and turn radii are measured in miles - they're not like your car. Once a collision like this is set up, there is often nothing that can be done to avert it.

The weather here is not perfectly clear, but visibility is still several miles. How could this happen? One ship does the ramming, the other gets rammed, but which vessel is at fault? There's no way to tell without seeing the courses that led up to the collision, and even then, maybe they are both at fault. Fortunately, they don't hit hard.

In this video, things move much faster, to a tragic end. The video begins just after the smaller vessel has been hit by the larger. It is a fatal blow, and the 'victim' sinks in minutes, taking 3 crew and 1 passenger with it. In this collision, the weather is largely to blame - there is fog and a rain squall obscuring visibility. Still, under such conditions, neither ship was using their radar set? Who was at fault? No decision was ever handed down. It takes two ...

This collision is inexplicable. By the prop wash, you can see the larger vessel is in full reverse. One of them is blowing their horn continuously, yet the smaller vessel seems to be oblivious. Once the larger vessel goes into reverse, it loses steering and can only go straight ahead, but the smaller vessel could easily have turned away to starboard. My guess is that in the minutes leading up to the collision, the smaller vessel cut in front of the larger one from starboard to port. Who was driving? Probably no one. This looks to me like the smaller vessel is clearly at fault, even though it is the one getting struck.

Compared to modern motor ships, sailing ships are stunningly unmaneuverable. Last-minute collision avoidance is basically impossible. Fog has always been a big cause of collisions, as well as darkness and rain. You'd think that in this age of radar and GPS, poor visibility would not be a problem, but there is still no substitute for being able to see with your own eyes. Too often, even with all the modern technology available to them, people just don't use it.

Almost all collisions at sea are the result of human error. Most often, someone simply was not paying attention. Or going too fast. Commercial fishermen work themselves to exhaustion, then fall asleep at the wheel. Tugboat skippers get distracted. Etc. A lot of small-boaters are simply idiots, and there are also drugs and alcohol. Some collisions are the result of mechanical failure, such as the Mohawk, whose steering gear went awry and drove her into the path of the Talisman, but such cases are the minority.

Collisions can also occur with the shoreline, buoys, navigational structures, floating debris, and anything else that is out there. Shouldn't forget icebergs. If they ever build that offshore wind farm, it will be bowling for windmills. Sunken windmills might make pretty cool dive sites. When a ship collides with a fixed object, the legal term is 'allision' rather than collision.

There are 'rules of the road' at sea, much like driving on land. Ships are supposed to pass each other 'port to port', or on the left side, like driving car. Powered vessels are supposed to yield to or avoid sailing vessels, while vessels that are encumbered, ie towing, dredging, etc, have precedence over all.

Below is an article I found that details a collision between two ships:

Real Life Accident: Collision Leads To Massive Explosion, Kills Nine Crew Members

By MARS Reports, May 25, 2016

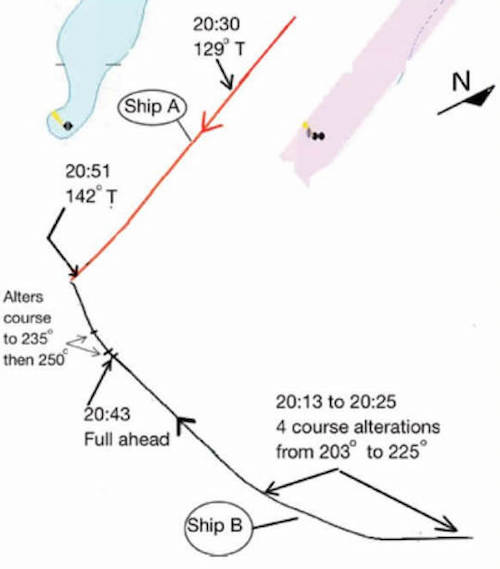

Several vessels, including Ship A and Ship C, were in a traffic lane heading about 130 degrees true. Ship B was in the process of crossing this traffic lane in order to integrate the opposite-bound lane. Visibility was good and seas were light.

On the crossing vessel, Ship B, the 3rd officer was OOW ( Officer on Watch. ) The Chief Officer (CO) and the 2nd officer were present on the bridge too, as was a helmsman. The CO was plotting targets on the ARPA radar to assist the OOW. The Master was also on the bridge from time to time monitoring the traffic. Initially, the 2nd officer was setting up the GPS units, but afterwards he was chatting and joking with the OOW and CO in addition to catching up with some work on the chart table. The 2nd officer’s presence appears to have been a source of distraction to the OOW and the CO.

Image credits: nautinst.org

The OOW on Ship B stated they would allow Ship A to pass ahead. The OOW on Ship A expressed surprise at this, as he had initially expected Ship B to alter course to port to join the traffic lane. When Ship B’s OOW then declared their intention to alter course to starboard, Ship A’s OOW considered this as an acceptable course of action for a crossing situation.

Later, the OOW of Ship A had identified that a close-quarters situation was continuing to develop with Ship B. He expressed concern on the VHF radio several times; a bigger alteration of course to starboard by Ship B was urgently required.

At 20:45, the CO on ship B informed the OOW that one of the targets was a false echo. This was an incorrect assumption and could easily have been clarified by visual observation. In fact, the bridge team had mistaken Ship C, also in the traffic lane, for Ship A, and assumed the actual echo of Ship A was a false echo. In the final minutes before the collision, the team on Ship B also mistakenly identified a fourth ship as Ship A. At 20.52 a collision occurred between Ship A and Ship B; Ship B was at about 11kt ( full ahead maneuvering ) and Ship A was at 13.5kt ( full ahead sea speed. )

A massive explosion occurred on Ship A as a cargo tank ruptured and naphtha was spilled and ignited. The ignited spill engulfed the sea surrounding the two vessels. On Ship A, nine crew members were killed and other crew members injured. Three crew members were injured onboard Ship B. Both vessels incurred substantial fire and structural damage as a result of the collision. Shockingly, of the many vessels in the vicinity at the time of the accident only one stopped to assist.

Some of the findings of the official report were as follows:

- This collision highlights the importance of effective, well-managed lookout techniques with correct implementation of the COLREGs* in as bold and timely a manner as possible.

- This case also highlights the importance for vessels to avoid becoming severely restricted by other vessels so as to limit their ability to comply with the COLREGs. Adequate contingency room should always be left to provide an escape route should other vessels appear not to be complying.

- The bridge team on vessel B were continually distracted from their lookout duties by laughing and joking on the bridge among themselves and also with other crew members on the bridge.

- Ship A was considered to be a false echo by the Ship B team, who also mistook Ship C for Ship A. Greater emphasis on comparing ships observed visually against the information presented by the electronic navigation aids was required. l Small and arbitrary alterations of course were made by Ship B without knowing what effect the actions would have.

- There was no use of the 'Trial Maneuver' function on the radar of Ship B. The team proceeded with indications of low CPAs and without realizing the steady compass bearings with Ship A. **

Lessons learned:

- Both vessels were proceeding at full speed at the time of collision, yet one of the safest of time-proven tactics is to slow down when unsure of the developing situation or of the intentions of the opposite party.

- Keep the bridge clear of chit chat and business unrelated to navigating the ship when in high risk areas, high traffic areas or at all other times when maximum concentration is needed.

- Course alterations should be as bold as possible so as to make your intentions known to the other vessels.

- When two ships in your vicinity collide and explode, do your best to stay safe but also render what assistance you can to the fellow mariners involved. Do not sail away as if nothing had happened.

* International Regulations for Preventing collisions at Sea 1972

** Any moving object that approaches on a steady relative bearing is on a collision course with you. You can see this even in your car: if another car is crossing your path and stays in the same spot on the windshield as the distance closes, you are going to hit.

Who hits who is often a matter of split-second timing at the last moment. Who is at fault is another matter entirely. For example, here is the course plot of the Andrea Doria and the Stockholm:

Stockholm was outbound inshore of the inbound shipping lane, Andrea Doria was inbound in the inbound lane. But shipping lanes then were more suggestions than rules or laws. Andrea Doria was in heavy fog, Stockholm was not.

If both vessels had simply gone straight and made an improper but otherwise safe starboard-to-starboard passing, neither one would have made history. Instead, Stockholm attempted to make a proper port-to-port passing, cutting in front of the Andrea Doria. The Andrea Doria was apparently not paying attention, and altered course to widen the distance for a starboard-to-starboard passing. In the process, she maneuvered directly into the path of the Stockholm.

Stockholm was doing the technically correct thing, although in this case probably not the right thing. Andrea Doria made what would have been a sensible maneuver, ten minutes earlier. Who is to blame? I'd say both of them, the Doria for not keeping up with events on the radar scope, and the Stockholm for making an unexpected maneuver. Both ships also could have communicated via radio.

If the Stockholm had been a little faster, or the Doria a little slower, or the courses altered just a tiny bit, we could have the following headline instead:

Andrea Doria Slices Stockholm in Two

Swedish Ship Sinks In Minutes, Few Survivors

In the same vein:

Stolt Dagali Bumps Shalom

Liner Badly Scraped, Will Need Paint Job