Mullica River Wrecks

The Mullica River

Chapter 4

The Mullica River Shipwrecks and the Revolutionary War

reprinted from

Hidden History of Maritime New Jersey

Steve Nagiewicz

New Jersey has commonly been known as the "Crossroads of the American Revolution." So many of the major Revolutionary War battles were fought here at places that jump off the pages of our history textbooks, like the Battles of Monmouth, Princeton, and Trenton and, of course, the iconic Delaware Crossing on Christmas Day by General George Washington in 1776. Washington and his main army, it seems, had spent more time in New Jersey than any other place. Of course, New Jersey's geographic position between New York and Philadelphia was a large part of that "Crossroads" title. Not surprisingly, the ocean provided another type of crossroad - one that was faster, more direct, and with the ability to send large amounts of supplies and troops by sea and along our coastline.

All of this makes the following tale all the more interesting. In the late 1700s, southern New Jersey was largely uninhabited. Long Beach and Absecon Islands were simply barrier islands, home to the occasional fisherman, Indian, or a hardy settler. Atlantic City wouldn't become a town until 1854. The South Jersey coastline was an ideal location for smuggling and privateering. I'm sure the British simply called the residents "pirates." South Jersey notable residents Richard Somers, John Cox, and Richard Wescoat all were engaged in privateering. Colonel Somers's ships would occasionally supply the Continental Congress with gunpowder, shot and flints imported from the West Indies via his port in Somers Point. Cox and Wescoat worked the iron bogs at Batsto and salt works along Great Bay. Cox and Wescoat would figure in the upcoming Battle of Chestnut Neck on the Mullica River or, as it was known then, Little Egg Harbor River.

Southern New Jersey and especially its coastal sections played an important yet largely unknown - or perhaps just an untold - part in the fight for independence in the Revolutionary War. It's the story about Chestnut Creek, which was a small settlement along the river in 1778. The settlement would eventually become the town of Port Republic. But that's all part of this tale.

Colonial privateers operated out of the tiny inlets along the South Jersey coastline. These small, quick, privately owned, and operated sailing ships would sneak out of Great Egg Inlet and raid the British merchant ships moving material and products along the coast. Colonial privateers were issued letters of marque by the Continental Congress authorizing as many as 1,697 privateers during the American Revolution. The privateers from Little Egg Harbor were in a good position to attack merchant ships traveling along its coast. The cargoes were then sold and the proceeds divided up by the government's Court of Admiralty. The ships' owners, captains, crews and, of course, the government all got specific shares, regulated by a Colonial Admiralty Court.

Along the South Jersey coast, these sales took place at Chestnut Neck ( a small village at the mouth of the Little Egg Harbor River, now the Mullica ), the Forks ( a larger settlement farther up the river ) and at Mays Landing ( on the Great Egg Harbor River. ) Large warehouses were built to hold the cargoes while they awaited sales and shipment. This entire area was important to the colonial forces as bog iron in Batsto was forged into cannon and shot and other iron materials for the Congress. The men who worked these iron bog furnaces were so important that they were immune from required service in the colonial militia. Also around Great Bay were numerous salt works. Salt was a highly-prized commodity at a time when vast quantities of food needed to be preserved for use by armies and aboard ships.

The settlement at Chestnut Neck was prospering from privateering operations, but the privateers knew it was only a matter of time before the British would strike somewhere to try and stop the loss of their merchant ships from these "pirates," as the British commanders called them. To protect themselves and their operations, in 1777 the privateers erected a fort at the water's edge to keep Chestnut Neck safe and also prevent the British from attacking Batsto Iron Works, which was a valuable asset for Continental forces. Richard Wescoat provided the funds to build the fort.

Oddly, the fort and the platform atop the hill behind it never had cannons installed, even though placements were made for them. It would prove to be a costly omission, as their presence would have made a contribution in the upcoming battle.

By late summer of 1778, about thirty ships and their cargoes were sold at both the Forks and Chestnut Neck. Six more ships were sold off in September at Chestnut Neck. These were a huge loss for the British and this was probably the last straw for the British. In New York, General Clinton and Admiral Gambier decide to organize an expedition to wipe out the privateering operations at Little Egg Harbor and destroy the ironworks at Batsto. The British would know the expedition as "The Egg Harbor Expedition." Word leaked out - probably through sympathizers - to the Patriots about the British fleet to destroy the privateers, and a militia issued a warning to coastal communities of this pending expedition. But while the threat was known, the specific destinations were still unknown. Late on the evening of September 30, Commander Henry Colins, on the newly commissioned HMS Zebra, and fifteen other ships left New York Harbor. A storm and heavy seas slowed the fleet's progress, but they arrived at Little Egg Harbor Bay on October 4.

Because of the warning by colonial sympathizers in New York, several of the larger ships at Chestnut Neck were able to put to sea before the British arrived. Other vessels were sent farther upriver. The British reached Chestnut Neck on October 5, 1778. Light ships of shallow draft were able to set up a blockade of the bay to prevent escaping privateers, but without knowledgeable local pilots, their sail upriver was slow. At daybreak on October 6, the attack began. By late afternoon, the better-armed British forces routed the small militia at Chestnut Neck. British cannon and overwhelming numbers of men forced the small militia and the settlement residents to withdraw. Had the fort possessed and used cannon the outcome would surely have been different.

Commander Colins found ten prize vessels still at Chestnut Neck. He ordered the town and all the vessels to be dismantled, set afire and the ships scuttled. It took all night and until noon on the seventh. Colonel Ferguson, under General Clinton's command, decided to take his soldiers to raid the north shore of Great Bay and the salt works. They destroyed two landings, three salt works, and ten buildings owned by Patriots. Having taken care of destroying the settlement, it was time to leave - but it was not as easy they might have hoped. Two of the British ships were aground. The HMS Zebra also ran aground, and the British could not get her free. On October 21, 1778, the British set fire to her and watched as her magazines exploded the ship to pieces. It was somewhat of a disappointment that the British lost a new warship while only partially achieving their mission to eliminate the rebel pirates of the Mullica. Chestnut Neck continued to operate privateers after this attack, but the settlement was not rebuilt, nor did its residents ever return, having fled to the inland villages. The area would later become the town of Port Republic.

Fast-forward to 1985, when maritime history experts and divers discovered the remains of two ships that were sunk by the British in the murky Mullica River during the Revolutionary War. The Atlantic Alliance for Maritime Heritage Conservation surveyed, mapped, and photographed the river-bottom locations of the ships. The sites of two submerged ships had been pinpointed years earlier and are listed as Mullica River/Chestnut Neck Archaeological Historic District (ID#385) on the National Register of Historic Landmark Sites, but the divers reported that they had found two more wrecks and may have found a third. It's possible that one of the wrecks was a British merchant ship while the other was a two-masted sloop, which is believed to be American. The discovery of this wreck and perhaps others still undiscovered in the silty waters of the Mullica will provide new information on American shipbuilding in the colonial period as archaeologists have opportunities to examine the wreckage.

Researchers from Stockton University's Marine and Environmental Science Research Field Station, located on Nacote Creek, were surveying the river looking for abandoned fish pots or, as they are often called, ghost pots. In the course of their mapping, they recorded side-scan sonar images of several wrecks buried in the mud along the banks of what was the Chestnut Neck area. Are these the burned vessels, and is one of them the HMS Zebra? Their interest peaked after finding these shipwrecks, researchers from Stockton University continued their search - only to uncover two potential targets farther upriver that match the age and construction of the Revolutionary War prizes. What a great ending to a tale seldom told for over 230 years!

About the Mullica River

The Mullica River headwaters originate in central Camden County near Berlin. Most developed land and upland agriculture is found in the headwater areas of the Mullica River. The river then flows for about 81.4 kilometers ( 50.6 miles ) across Atlantic, Ocean, and Burlington Counties and drains into Great Bay. The Mullica River Watershed covers 1,474 square kilometers of the Mullica River Basin. The unconfined Kirkwood-Cohansey aquifer system underlies the Mullica River Basin. The river flows generally east-southeast across the state, crossing the Wharton State Forest, where it receives the Batsto, Wading, and Bass Rivers. Mullica broadens into a navigable river for only approximately 32 kilometers ( 20 miles ) of its entire length.

The estuary of Great Bay or Great Egg Harbor Bay is considered one of the least-impacted marine wetlands habitats in the northeastern United States, due to the fact that most of the land in the Mullica River watershed is preserved or sparsely developed state-owned pine forests and scrubland and various wildlife management areas. In fact, the Mullica flows almost entirely within the Pinelands National Preserve. The Pinelands is classified as a United States Biosphere Reserve and in 1978 was established by Congress as the country's first National Reserve. The Reserve occupies 21 percent of the land area of the State of New Jersey.

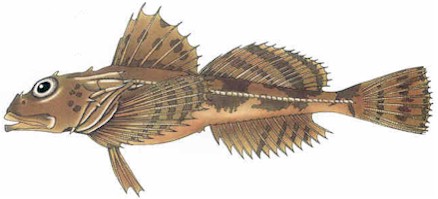

Where a freshwater river meets the saltwater of the ocean are called Estuaries. This productive estuary supports a diversity of fish species, including striped bass, flounder, and bunker. It contains nesting habitat for ospreys, bald eagles, and myriad other bird species usually found in marine wetlands and marshes. It is an important nursery area for the region's blue crab and hard-shell clam fisheries. Tidal creeks also support populations of the northern diamondback terrapin, which is listed by the federal government as a species of special concern.

Much of the area where the Mullica emptied into the Great Bay is part of the Edwin B. Forsythe National Wildlife Refuge as is the Jacques Cousteau National Estuarine Research Reserve (JCNERR). JCNERR is one of the twenty-eight national estuarine reserves created to promote the responsible use and management of the nation's estuaries. Great Egg Inlet - like the Great Egg Bay - was named for the vast amount of bird's eggs found by the early European explorers from the thousands of migratory birds that enjoy the marshes and warm-water nurseries that the estuary supplies. Both the Edwin B. Forsythe National Wildlife Refuge and the Jacques Cousteau National Estuarine Research Reserve are important ecosystems for the shore.

Available Now:

Hidden History of Maritime New Jersey

by Steve Nagiewicz

An estimated three thousand shipwrecks lie off the coast of New Jersey -- but these icy waters hold more mysteries than sunken hulls. Ancient arrowheads found on the shoreline of Sandy Hook reveal Native American settlement before the land was flooded by melting glaciers. In 1854, 240 passengers of the New Era clipper ship met their fate off Deal Beach. Nobody knows what happened to two hydrogen bombs the United States Air Force lost near Atlantic City in 1957. Lessons from such tragic wrecks and dangerous missteps urged the development of safer ships and the U.S. Coast Guard. Captain Stephen D. Nagiewicz uncovers curious tales of storms, heroism, and oddities from New Jersey's maritime past. 176 pages, illustrated, softcover

Get your signed copy direct from the author: $20 + $3 S&H (USA)

Questions or Inquiries?

Just want to say Hello? Sign the .