Freighter (1/2)

A cargo ship or freighter is any sort of ship that carries goods and materials from one port to another. Thousands of cargo carriers ply the world's seas and oceans each year; they handle the bulk of international trade. Cargo ships are usually specially designed for the task, being equipped with cranes and other mechanisms to load and unload, and come in all sizes. Specialized types of cargo vessels include container ships and bulk carriers. ( Tankers and supertankers are also cargo ships, although they are habitually thought of as a separate category. )

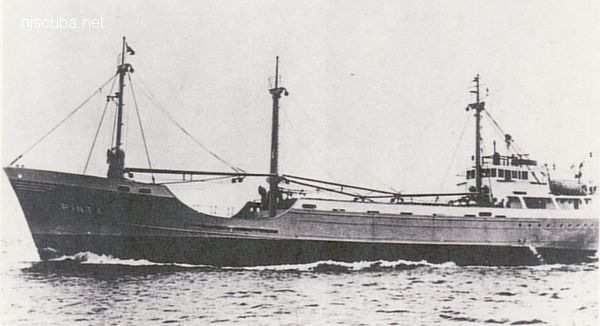

Larger cargo ships are generally operated by shipping lines. Such vessels usually follow a set schedule and carry diverse cargoes for many customers as part of a generalized freight service. Smaller vessels, such as coasters and tramp steamers, are often owned by their operators. Tramps have no set schedule and sail wherever their next contract takes them, generally carrying a bulk cargo for a single customer.

"Cargo" technically refers to the goods carried aboard the ship for hire, while "freight" refers to the compensation the ship receives for carrying the cargo, thus the expression "Pay the freight." Some freighters are also equipped to carry a limited number of passengers, although not in any grand style.

Pre-World War II

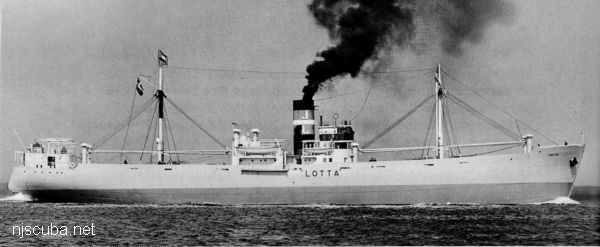

Prior to World War II, and for a number of years after, there was little variation in freighter design. While size ranged between 100 and 500 feet, all ships were laid out basically the same. Engines and machinery were amidships, with crew accommodations built above in a small superstructure. Topping the superstructure was the bridge, affording the captain the best possible view forward and around. Larger vessels might also have a small structure at the stern; smaller vessels might have the entire superstructure at the stern.

One exception was the Great Lakes steamer, which placed the bridge at the extreme bow, with another above-deck structure at the stern for crew and machinery. While this design exposes the bridge to rough weather and waves breaking over the bow, it affords the absolute best view forward; a fair compromise for the confined and generally sheltered waters of the lakes.

Cargo in old freighters was carried in holds - cavernous spaces inside the hull of the ship, covered with large waterproof hatches in the deck. Masts and booms (cranes) over the holds allowed the ship to load and unload itself in primitive port facilities. A freighter could carry anything that could fit in its hold - there was little specialization. All cargo - whether bags of coffee, crated goods, automobiles, or livestock - was lifted up and lowered into the holds, one piece at a time, except for bulk cargos like grain, ores, and crushed stone, which could be loaded directly into the holds by conveyor belt or bucket crane.

A collier was a vessel built to transport coal. The bulk nature of the collier's cargo resulted in a design that was superficially similar to an oil tanker, except that a collier had rows of cargo hatches along the deck. Today coal is far less important as fuel than it was in the past. Nowadays most coal is transported inland by rail or river barge, and the collier is all but extinct. My father made one trip on one as a sailor and said it was a dirty, unpleasant experience, with no escape from the black coal dust that permeated the entire ship. The U.S.S. Langley, America's first aircraft carrier, was a converted collier.

All of the freighter wrecks and artificial reefs available to scuba divers in the New Jersey / New York area are of this same basic design, and almost all pre-date World War II. Below are a number of modern developments in cargo ships, which you may see during your surface interval.

World War II: Liberty Ships & Victory Ships

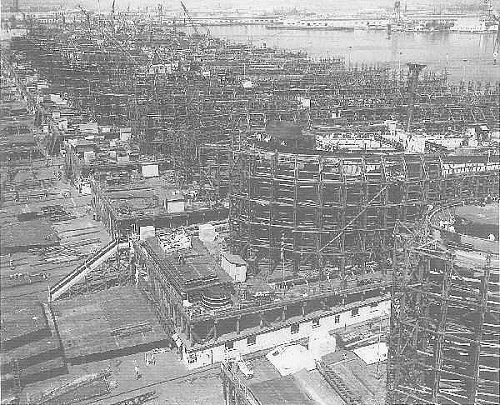

When war broke out in Europe in September 1939, the merchant fleet was caught unprepared to handle a massive sealift of war material. With continental Europe under German control, and Great Britain under devastating air attack, President Franklin Roosevelt decided to increase the pace of production to provide ships to America's British allies. The result was the emergency fleet program, which introduced the assembly-line production of standardized ships--the Liberty ships--in 1941. The Liberty ship represented the design solution that would fill the need for an emergency type of simple, standardized cargo steamer. Based on a British design, it could be mass-produced cheaply and quickly using assembly-line methods and could easily be converted to individual military service needs. The United States designated this new type of ship the EC2 ( E for emergency, C for cargo and 2 for a medium-sized ship between 400 and 450 feet at the waterline. ) Production speed grew more important as German submarines sank ships trying to break Hitler's naval blockade of Great Britain. The Allies needed ships by the hundreds to replace these losses and to increase the flow of supplies to England and, later, the Soviet Union.

The first of these new ships was launched on September 27, 1941. It was named the SS Patrick Henry after the American Revolutionary War patriot who had famously declared, "Give me liberty, or give me death." Consequently, all the EC2-type of emergency cargo ships came to be known as Liberty ships. Naming nearly 3,000 ships turned out to be harder than people thought. Unlike the later Victory ships, there was no plan for how the Liberty ships would be named. In the end, the Liberties were named for people from all walks of life. Ships were named after patriots and heroes of the Revolutionary War. They were named after famous politicians ( Abraham Lincoln to Simon Bolivar ), scientists ( George Washington Carver to Alexander Graham Bell ), artists ( Gilbert Stuart to Gutzon Borglum who sculpted Mt. Rushmore ), and explorers ( Daniel Boone to Robert E. Peary ). One ship was named the SS Stage Door Canteen after the famous USO club for military service members, while another was named the SS USO, in honor of the United Service Organization itself.

The Liberty ships were slightly over 441 feet long and 57 feet wide. They used a 2,500 horsepower steam engine to push them through the water at 11 knots ( approximately 12.5 miles per hour ). The ships had a range of 17,000 miles. Liberty ships had five cargo holds, three forward of the engine room, and two aft ( in the rear portion of the ship ). Each could carry 10,800 deadweight tons ( the weight of cargo a ship can carry ) or 4,380 net tons ( the amount of space available for cargo and passengers ). The crew quarters were located amidships.

Many technological advances were made during the Liberty shipbuilding program. A steel cold-rolling process was developed to save steel in the making of lightweight cargo booms. Welding techniques also advanced sufficiently to produce the first all-welded ships. Prefabrication was perfected, with complete deckhouses, double-bottom sections, stern-frame assemblies, and bow units speeding production of the ships. By 1944, the average time to build a ship was 42 days. In all, 2,751 Liberties were built between 1941 and 1945, making them the largest class of ships built worldwide.

Each Liberty ship carried a crew of between 38 and 62 civilian merchant sailors, and 21 to 40 naval personnel to operate defensive guns and communications equipment. The Merchant Marine served in World War II as a Military Auxiliary. Of the nearly quarter-million volunteer merchant mariners who served during World War II, over 9,000 died. Merchant sailors suffered a greater percentage of fatalities (3.9%) than any branch of the armed forces.

The Liberty ship was considered a "five-year vessel" ( an expendable, if necessary, material of war ) because it was not able to compete with non-emergency vessels in speed, equipment, and general serviceability. However, Liberties ended up doing well, plodding the seas for nearly 20 years after the end of World War II. Many Liberties were placed in the reserve fleet and several supported the Korean War. Other Liberties were sold off to shipping companies, where they formed the backbone of postwar merchant fleets whose commerce generated income to build the new ships of the 1950s and 1960s. However, age took its toll and by the mid-1960s the Liberties became too expensive to operate and were sold for scrap, their metal recycled. The first Liberty built, the Patrick Henry, was sent to the shipbreakers (scrap yard) in October 1958.

Of the nearly 3,000 Liberty ships built, 200 were lost during World War II to enemy action, weather, and accidents. Only two are still operational today, the SS Jeremiah O'Brien and the SS John W. Brown.

Victory Ships

In 1943, the U.S. Maritime Commission embarked on a program to design new types of emergency fleet ships, most importantly fast cargo vessels, to replace the slower Liberty ships. The standardized design adopted by the Commission called for a ship 445 feet long by 63 feet wide and made of steel. On April 28, 1943, the new ships were given the name "Victory" and designated the VC2 type ( V for Victory type, C for cargo, and 2 for a medium-sized ship between 400 and 450 feet long at the waterline. )

The Victory ships ultimately were slightly over 455 feet long and 62 feet wide. Like the Liberty ships, each had five cargo holds, three forward and two aft. The Victories could carry 10,850 deadweight tons ( the weight of cargo a ship can carry ) or 4,555 net tons ( the amount of space available for cargo and passengers ), a larger load than the Liberties could manage. Victory ships typically carried a crew of 62 civilian merchant sailors and 28 naval personnel to operate defensive guns and communications equipment. The crew quarters were located amidships. The Victory ships were different from the Liberty ships primarily in propulsion, the steam engine of the Liberty giving way to the more modern, faster steam turbine. The Victory ships had engines producing between 5,500 to 8,500 horsepower. Their cruising speed was 15-17 knots (approximately 18.5 miles per hour).

The ship profile and the construction techniques of the Victories were also different from the Liberties. One important feature of the Victory ship was in the internal design of the hull, the ship's framework. The Liberty ships had the frames inside the hull set 30 inches apart. This made the hull very rigid. This rigidity caused the hull to fracture in some of the ships. The Victory ships had their hull frames set 36 inches apart. Because the hull could flex, there was less danger of fracture.

The first Victory ship completed was the SS United Victory (built at Oregon Shipbuilding, Portland, OR), launched on January 12, 1944, and delivered February 28. The next 33 ships were named after member countries of the United Nations (e.g., SS Brazil Victory and SS USSR Victory [ both built by California Shipbuilding Corporation, Los Angeles, CA ], and SS Haiti Victory [ built by Permanente Metals Corporation, Yard 1, Richmond, CA ]). The ships that followed were named for cities and towns in the United States (e.g., SS Ames Victory [built by Oregon Shipbuilding], SS Las Vegas Victory [built by Permanente Metals Corporation, Yard 1] and SS Zanesville Victory [built by Bethlehem-Fairfield Shipyards, Inc., Baltimore, MD]) and for American colleges and universities (e.g., SS Adelphi Victory and SS Yale Victory [both built by Permanente Metals Corporation, Yard 2]). All of the ships' names ended with the suffix "Victory" with the exception of the 117 Victory Attack Transports that were named after state counties. The Maritime Commission built 414 Victory cargo ships and 117 Victory attack transports for a total of 531 vessels during the course of the war.

Victory ships formed a critical maritime link to the theaters of war. These fast, large-capacity carriers served honorably in both the Atlantic and Pacific theaters of war. Ninety-seven of the Victories were fitted out as troop carriers; the others carried food, fuel, ammunition, material, and supplies.

At the war's end, a number of Victory ships were offered for sale by the Maritime Commission. One hundred and seventy were sold, 20 were loaned to the U.S. Army and the rest were stored as part of the reserve fleet. When the Navy no longer needs to use a ship but wishes to reserve it for a future emergency, it tows the ship to storage harbors, empties it of all fuel and cargo, and seals its windows and doors. The ship is protected from salt-water corrosion by a cathodic protection system and the interior spaces are dehumidified. This technique is called "mothballing, " because it echoes how people preserve a wool sweater that is put away for the summer.

Some vessels were reactivated to serve during times of national crisis, including the Korean War, the Suez Canal closure of 1956, and the Vietnam War. Other vessels were retained as logistic support ships as part of the Military Sealift Command, which in 1970 became the single managing agency for the Department of Defense's ocean transportation needs. The command assumed responsibility for providing sealift and ocean transportation for all military services as well as for other government agencies. In 1959, eight Victory ships were reclassified and refitted as instrumentation, telemetry, and recovery ships for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) in support of America's space program. On August 11, 1960, the former SS Haiti Victory (renamed the USNS Haiti Victory (T-AK-238)) recovered the nose cone of the satellite Discoverer XIII, the first man-made object recovered from space.

Over the years, many ships in the reserve fleet have been sold for scrap, their metal to be recycled. Of the thousands of Liberty ships and Victory ships produced only a small number remain.

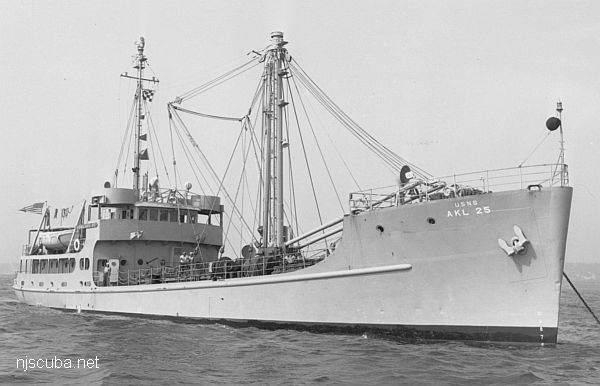

Of course, Liberty and Victory ships were not the only cargo vessels constructed during the war. The need for smaller ships and specialized types continued, and was filled by vessels like the AKL-class freighter, which were also built in large numbers, and carried on for many years after the war.