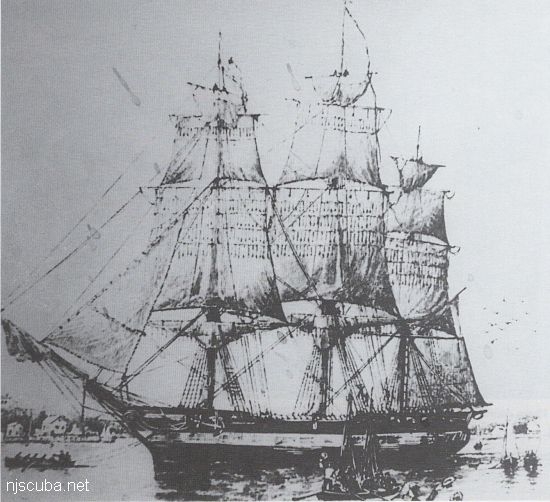

Shearwater (FS-411) (2/2)

The Omega Men

Catching fish in rough weather is only one of the challenges facing the menhaden fleet of Reedville, Va.

By Kathy Bergren Smith

At the bitter end of Route 360 on the Northern Neck of Virginia lies the Victorian village of Reedville, population 300. Founded in 1874 by a Maine fisherman, Elijah Reed, Reedville, from its start, has been all about Atlantic menhaden.

For generations, most people in Reedville, which consistently ranks in the top three U.S. ports by landings, have been associated with the catching and processing of this inedible fish. One by one, the factories have closed and the boats have gone where old boats go.

Today there is only one menhaden processing plant in Reedville: Omega Protein. I am heading there on a summer Sunday night to meet Capt. Lee Robbins and join his boat Shearwater for a purse seining trip.

"It looks like fishing is going to be pretty good tomorrow, we have a good fish report to work from," he says as we park in the fish processing plant's yard. A smokestack looms over a factory and several smaller buildings dot the yard. There is not the typical marina-like atmosphere around the fleet; in fact, the factory's chutes and tanks hide the boats.

We make our way to the docks where the whole fleet is tied up. Eleven boats range in length from 140 to 200 feet. Several are former Gulf of Mexico oil field service boats. Several others are converted WWII-era Army supply craft.

Each boat is configured alike: wheelhouse forward, fish holds amidships, and two 38-foot aluminum boats hang from davits above the stern. Netting is gathered in each of the small boats and draped across the cutout stern. Like the menhaden boats I watched as a child on the Jersey Shore, each mast is topped by a crow's nest and a boom secured by a cable mounted to it. The Shearwater is the fleet's second-largest boat at 166' x 32' with a molded depth of 11 feet. Twin GM 149 engines power the Shearwater.

As we tour the Shearwater's deck, Robbins calls to the Great Wicomico, tied alongside. Soon, the Great Wicomico's captain, Paul Somers, a fourth-generation waterman, and the boat's pilot, Jeffrey Dameron, appear at the rail. The men's genteel Tidewater accents seem to turn the clock back 100 years. Dameron's father piloted the menhaden boat Robbins' father, Meredith Robbins, skippered.

Talk inevitably turns to the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission's decision to place commercial catch limits on menhaden for the first time in Virginia's portion of the Chesapeake. ( Maryland banned purse seining in 1931. )

"I see it as a state's rights issue; you have all these states" - the commission has two members from each East Coast state from Maine to Florida - "that have closed their grounds to our boats, and now they are telling us that we can't fish here in Virginia?" Robbins says.

The 106,000-metric ton menhaden limit the commission set became effective July 1, 2006. It was imposed in response to mounting recreational fishing industry concern that "localized depletion" of menhaden in the bay is depriving the burgeoning striped bass population of its most important food source. ( In October, the commission was to consider Virginia's proposal to raise the cap to 109,000 metric tons. )

There is a dearth of population data for menhaden in the Chesapeake specifically. But benchmarks the commission itself set show the coast-wide stock is considered healthy.

"That right there is the 'smoking gun'," Robbins says. From the fisherman's perspective, managers are bowing to political pressure from a special interest group instead of using the best available science to make a decision.

Like so many other late-night discussions, at around midnight, the fishermen decide they can't solve the world's problems and they had better get some shut-eye before the grueling workweek begins at 4 a.m.

Questions or Inquiries? Contact

Just want to say Hello? Sign the Guest Book.