Paddlewheels

The paddlewheel predates even the steam engine. Horse-driven paddlewheel ferries have been in use for hundreds of years. Compared to screw-type propellers, the design and construction of a paddlewheel is much simpler, and therefore they remained the dominant method of propulsion through the mid-1800s, with some examples remaining in use until after World War II.

Compared with screw propellers, paddlewheels had a number of disadvantages. Greatest among these was efficiency - early on it was shown that in a tug-of-war, a propeller-ship would pull a paddle wheeler of equal size and power backwards. Paddlewheels were also much more delicate than propellers, especially in the stormy northern oceans, where waves have actually smashed the paddlewheels off a number of vessels, leaving them to drift, or limp home by sail if they were so-equipped. On a warship, a paddlewheel was likely to be the first thing shot away in a fight.

Paddlewheels also had a few advantages over propellers. They could operate in very shallow waters where a propeller would strike the bottom. Side-wheel paddleboats could operate in extremely tight quarters, literally spinning in place by putting one wheel in forward and the other in reverse. Most paddlewheels also function equally well in forward or reverse, unlike a propeller which is designed to go in one direction only. This made them ideal for use on ferries and tugboats, which often find themselves needing to go backwards.

Stern-wheel paddleboats could operate in debris-strewn waters since the wheel was protected from damage behind the boat. It was also much easier to repair a damaged paddlewheel than a propeller. Therefore, in the later 1800s, paddle wheelers came to dominate river and inland traffic, while the propeller found greater use in ocean traffic. Ultimately, however, the paddlewheel lost out to the propeller entirely, and today it is only found on antique vessels and a few excursion boats.

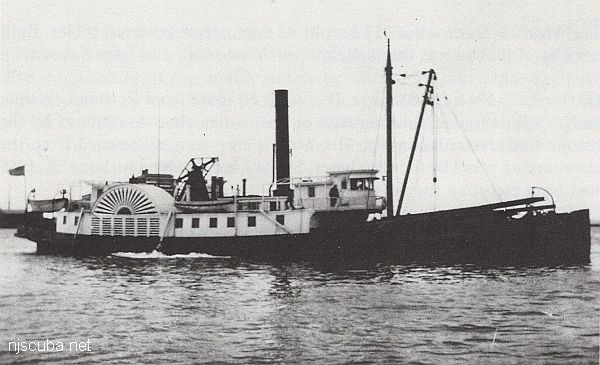

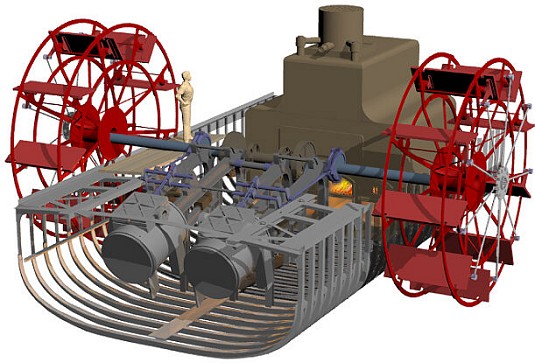

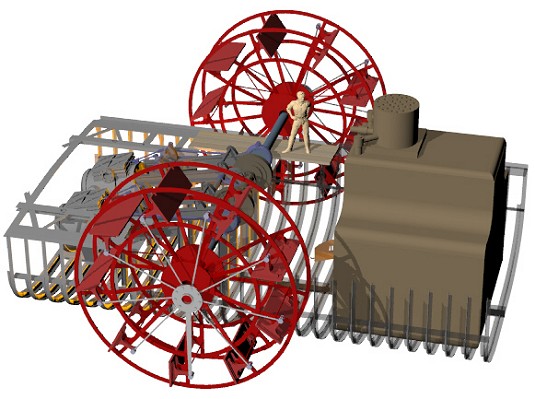

Above are two truly superb depictions of a Civil War-era side-wheel paddleboat's propulsion plant and wheels. The large brown object at the right is a fairly primitive low-pressure boiler. The gray barrel-like objects at the left are the vessel's two independent steam engines, each with a single cylinder. Horizontal direct-acting engines like this were typically found on European vessels, while American designers preferred upright walking-beam-type engines, as is evident in the photo of the Mistletoe above.

Since the two engines here are completely separate, they may be reversed independently of each other, giving the turn-on-a-dime capability described above. This is done not with a reverse gear as in an automobile, but by reversing the engine itself - a trick that is still used in some marine diesels today. Side-wheelers like this were much preferred over sternwheelers for open-ocean service, and I believe that all of the paddlewheel vessels listed in this website are side-wheelers.