Schooner Barge

The schooner barge was the final development of the working sailing ship. The design originally evolved in the 1870s on the Great Lakes, where it was found that sailing ships could be more profitably towed from place to place than sailed. No longer subject to the vagaries of the wind, such trips could be made on a scheduled basis, and with reduced labor costs. The idea spread into general use, resulting in the conversion of many sailing ships into barges. Ironically, most of the vessels that were converted to schooner barges were not actually schooners, but square-rigged ships. Square-riggers, with their large and expensive crews of skilled sailors, became uneconomical to operate in the face of ever-improving steam power, while more efficient schooners managed to compete for a few years longer.

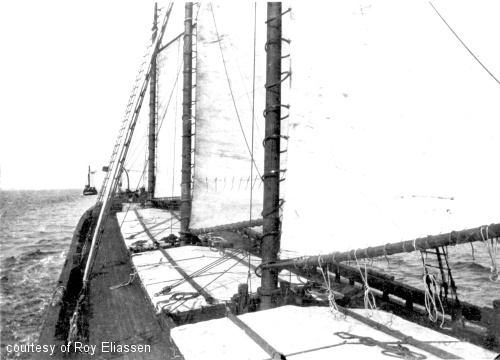

Schooner barges did not carry enough sail to be considered truly self-propelled. However, in an emergency, they could be sailed on their own, and it was not unheard-of for a lost schooner barge to make its way to port by itself.

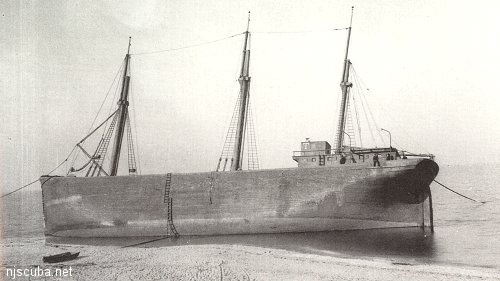

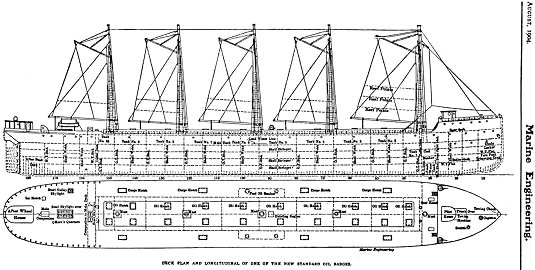

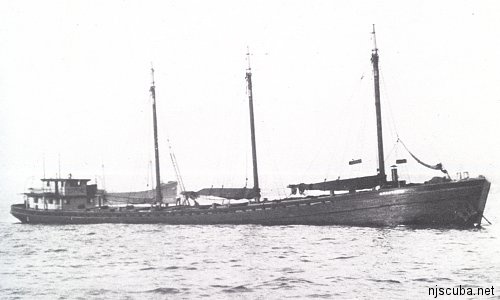

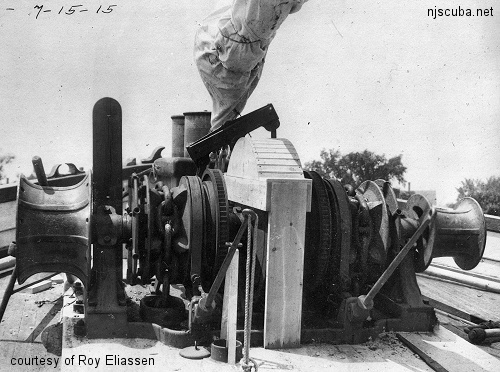

The schooner barge conversion was fairly straightforward: the upper masts, bowsprit, and rigging were removed, leaving just the lowest course of sails, which were schooner-rigged, regardless of how they had been before. Any forward deckhouse was removed, and loading hatches were installed along the length of the deck. A raised wheelhouse was installed aft to afford a better view for the steersman, and large towing bits were installed at bow and stern. Small boilers and auxiliary steam engines were installed in the bow to power the winches and booms in the absence of a large crew, which was reduced to three or four bargemen. The sails were used only under favorable conditions, to offload the towing vessel somewhat, and also in emergencies, as when a barge broke free of its tow. Compared to typical square barges, schooner barges were more seaworthy and streamlined, making them much better for use on the open sea.

In the 1890s, as the supply of old sailing ships began to dwindle and the old hulls wore out, many schooner barges were built new, predominantly in Maine and Connecticut, although elsewhere as well. This practice continued into the 1920s. The Dykes was one such vessel, the Pocopson was another. The majority of schooner barges were constructed of wood, although some later ones were built with iron or steel hulls and masts. Old steamers were also sometimes converted to schooner barges, but this was uncommon.

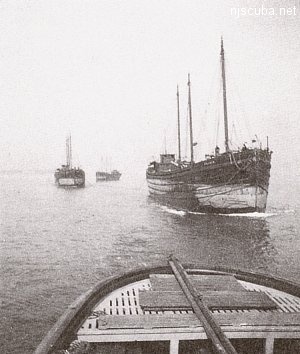

Most schooner barges were engaged in transporting coal, and many were owned by the railroad companies of the era, serving as sea-going extensions of the railways. Other cargoes included lumber, stone, ice, and anything else that could be profitably carried. Schooner barges were often towed in long strings of as many as six or more vessels. The entire assemblage could stretch up to a mile, a hazardous operation that was finally restricted in 1908 to four vessels including the tug. ( Nowadays it is rare to see even two barges under tow together. ) Many schooner barges were lost to accidents, collisions, groundings, weather, and simply old age.

Schooner barge use declined in the 1930s, and by World War II had all but ceased, although a few vessels continued in use into the 1950s. Several factors contributed to this: a general decline in the use of coal with the increased use of fuel oils, and a decline in the use of open-ocean towing, made obsolete by newer, safer, and more efficient self-propelled freighters. Barge traffic continues to this day, but mainly on inland routes. In these protected waters, the schooner barge's advantage of seaworthiness over a flat-bottomed square barge is outweighed by the ease of construction, handling, loading, and carrying capacity of that type, and so the schooner barge became extinct.

Schooner barges are probably the single most common type of shipwreck in area waters. At one point, several thousand schooner barges plied the waters off the East Coast, and there are scores of them sunk off our shores. The bottom of Long Island Sound is said to be "paved with coal" from sunken schooner barges. Unfortunately, such losses generally went unrecorded in the public record, especially if the crew was gotten off safely. This makes specific identifications of wrecks impossible in most cases.

Schooner barge wrecks exhibit a number of common characteristics, as evidenced by this drawing of the Hankins, above. Note the three parallel wooden walls, with the keel forming the center one. Also typical is the machinery concentrated near the bow, and the north or east orientation of the wreck, into the storm that sank it. Coal may or may not be found, depending on whether it was salvaged or scattered away by the sea.