Sailing Ships

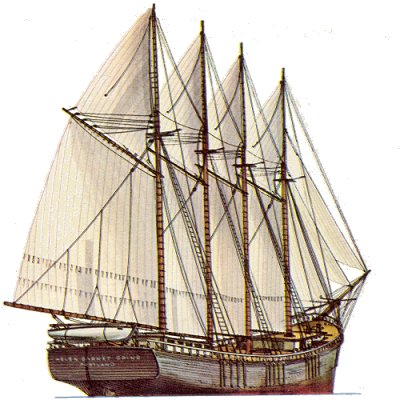

A packet ship of the early 1800s. Of note is the way the sails on the mainmast are set backward, against the sails on the fore- and mizzen- masts. Known as "backing", this was how a square-rigged ship "put on the brakes" to slow or stop without actually furling the sails.

Wind power has been used by mankind for millennia. Almost every human culture has constructed sailing vessels of some kind, from crude log or reed rafts to the highly developed wind-jammers of the early twentieth century. Many of these vessels were the most complex and technologically advanced machines of their time - equivalent to our jet airliners.

Sailing ships are classified according to their rigging. To a landlubber, anything bigger than a rowboat is a ship, but to the old-time sailors, there was a world of difference based on the configuration of the sails.

Fore-and-aft rigged sails are asymmetrical and set behind the mast on booms. They can be swung from one side to the other, depending on the wind. Thus fore-and-aft sails can work the wind on both sides of the canvas. A fore-and-aft rigged ship carries less sail area than a square-rigged ship of equal size and is therefore not as fast. This is more than made up for in ease of handling and maneuverability - they actually sail best against the wind.

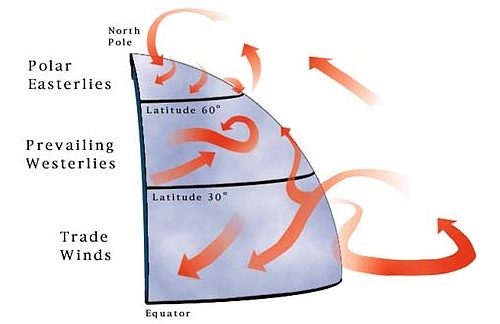

Square-rigged ships have predominantly rectangular sails set symmetrically across the masts. Square-rigged sails catch the wind on one side only. They are highly suited for sailing downwind on the open sea but are clumsy and inefficient when sailing into the wind. Fortunately, all the navigable oceans have predictable patterns of air circulation - huge gyres which rotate clockwise in the northern hemisphere, and the opposite in the southern.

These are commonly known as the "Trade Winds" and "Prevailing Westerlies", and will carry a vessel westward near the equator, and eastward at middle latitudes, and westward again in polar regions, facilitating a round-trip route that is downwind in both directions! Although this has been possible for as long as the Atlantic Ocean has existed, European mariners did not generally figure it out until the sixteenth century. This was what gave the Portuguese their head start in exploring the New World - they were the first to understand the winds, and kept the knowledge a guarded secret.

Rigging of Sailing Vessels

All the rigid members which carry the sail of a vessel are called spars.

- The vertical spars are called masts

- An angled spar extending from the bow is called a bowsprit

- Horizontal spars which cross the masts are called yards

- A horizontal or angled spar which is anchored at one end to a mast and supports the top of a sail is called a gaff

- A horizontal or angled spar which is anchored at one end to a mast and supports the foot of a sail is called a boom

Sloops & Schooners

| The Sloop is a small vessel with one (or sometimes two) masts and a fore-and-aft rig. The mainsail is attached to a gaff at the head and a boom at the foot, and above it a gaff-topsail can be set. Before the mast are one or more jibs. The Catboat is a sloop with the mast mounted in the bow rather than amidships. |

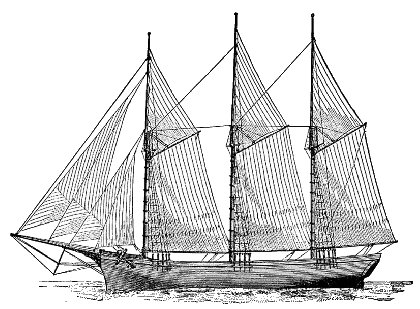

| The Schooner is a larger vessel than a sloop, with all masts fore-and-aft rigged. The earliest schooners had two masts, but the most popular designs had three or four; in later times the number increased to as many as six. The only seven-masted schooner proved to be impractical. 'Baldheaded' schooners lack topmasts and topsails. |

| The Topsail Schooner is a two-masted vessel, the mainmast of which has a fore-and-aft mainsail and gaff-topsail identical to those of an ordinary schooner. Both masts are made in two spars, but the lower foremast is a little shorter than the corresponding spar of the mainmast, and the topmast is a little longer. Speedy topsail schooners were also known as "Baltimore Clippers." |

| The Schooner Barge was a sailing vessel that was either converted or purpose-built to be towed by a tugboat but retained some sailing ability to assist the tow in favorable winds, and for emergencies. The rig was simplified to a single fore-and-aft mainsail on each mast, and a single jib, with no bowsprit, topmasts, or topsails. |

Brigs

| The full-rigged Brig is a vessel with two masts, fore and main, both of which are fully square-rigged. The mainmast also carries a small fore-and-aft sail which improves maneuverability - brigs were known to be very "handy" vessels. A Snow is a brig with an auxiliary mast attached to the mainmast for the fore-and-aft sail. Not found outside Europe. |  |

| The Brigantine is a vessel with two masts, whose foremast is square-rigged like that of the full-rigged brig. The mainmast, however, carries a large fore-and-aft mainsail, above which are two or three yards on which are carried a square main-topsail and topgallant sail. |  |

| The Hermaphrodite Brig is a vessel whose foremast is identical to the full-rigged brig and brigantine, and whose mainmast is that of a schooner; the mainmast is made in two spars and carries no yards. Half brig, half schooner - hermaphrodite. I wonder how many sailors could even spell that. |  |

Ships & Barks

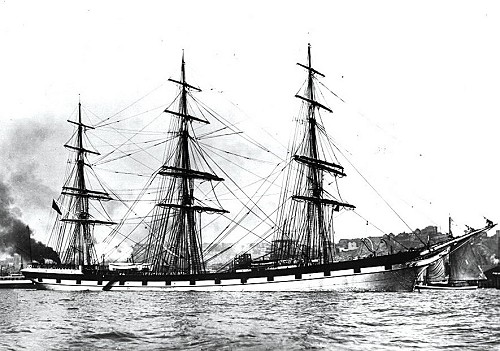

| The Ship is a vessel of three or more square-rigged masts, each composed of a lower-mast, top-mast, and topgallant mast. Each is outfitted with yards and a full complement of square sails. The mizzenmast also carries a small fore-and-aft sail to assist with steering. Four-masted ships were common, and a single five-masted ship was constructed. |

| The Bark ( or Barque ) is a vessel of three or more masts, similar to a Ship. The mizzenmast (aft-most) is fore-and-aft rigged, while all other masts are square-rigged. The largest sailing vessel ever built was a five-masted steel bark. Four-masted barks were common workhorses. |

| The Barkentine is a vessel of at least three masts. The foremast is square-rigged, while all other masts are fore-and-aft rigged. This was a popular design in the Pacific, combining the downwind speed of a square-rigged ship with the economy and coastal maneuverability of a schooner. Barkentines carried as many as six masts, although four or five was more typical. |

All of these distinctions may seem excessive and even silly to us today, in an age when sailing ships are antique curiosities - a "Tall Ships" parade once a year in New York Harbor. But in another age, the differences between different kinds of sailing rigs was quite important - the difference between a maneuverable coaster and a fast sea-going clipper.

There were many variations in a sailing ship's rigging. On square-rigged ships, much of the rigging, including the upper masts and outer spars, could be taken down or erected at sea as needed and was stored on deck or below when not in use. In stormy high latitudes the upper rigging was reduced to lower the vessel's center of gravity and reduce the tendency to heel over in the wind, while in the light airs and calm seas of the tropics, a full spread of sail was put up to make the best of scant breezes. Such changes were typical on sailing whaleships, which often transited from the North Atlantic down through the Caribbean and south around the tip of South America, then north again in the Pacific to the whaling grounds off Alaska, on voyages that might last several years. Many vessels were completely re-rigged over the course of their working careers.

Most sailing ships were constructed of wood, although later ones were built with iron or steel hulls and masts. The design life of a pine-built sailing ship of the nineteenth century was only about twenty years, although many lasted longer. Some clipper ships actually recouped their construction costs on their first voyage. Such a vessel could be considered essentially disposable. I wonder if the crews felt the same way.

Unfortunately, it is all but impossible to determine what type of rig a sailing ship was from the remains on the bottom, unless some artifact is discovered that leads to a historical identification of the wreck. Almost no sailing shipwrecks have masts or spars remaining, as these were either pulled down or worked loose and floated away. Most of the wrecks in the area are schooners or schooner barges since this type of vessel far outnumbered the rest over the years. One clue to the age of a wreck is the discovery of dead-eyes or turnbuckles.

Square-Riggers

Lightning - The most famous American sailing clipper ship, and probably the fastest ever - over 18 knots. The extra outboard sails were known as "studding-sails", or "stuns'ls" for short.

The evolution of the ocean-going sailing ship begins in the Middle Ages with clumsy, tub-like, yet seaworthy square-rigged vessels such as those that carried the early explorers and colonists. Over time, these vessels grew in size and speed, with great improvements in hull form, sails, rigging, and steering. With commensurate improvements in navigation and more and more complete and accurate charts, sailing on the open sea went from near-suicidal explorations in the 1500s to commonplace and fairly reliable transportation in the 1700s. In the early 1800s, sail had become reliable enough that regularly scheduled service was attempted, although this was soon eclipsed by steam.

The clipper was the epitome of sailing ship development. Carrying huge spreads of canvas, some clippers were capable of speeds that would be enviable even for modern motor ships. Such speed came at a price though - with large crews, small payloads, and high maintenance costs, clipper ships had only a brief heyday in the 1850s to 1860s, before they were made uneconomical by rising labor costs, steamships, schooners, overland routes and railroads, and the opening of short cuts such as the Suez Canal in 1869. Sadly, of all these powerful, sleek, and graceful sailors, only the Cutty Sark survives.

The era of the square-rigged ship was essentially over by the turn of the century ( that's 1900, not 2000, for you kids ! ) Wind simply could not compete with steam. The last few-dozen working square-rigged ships were retired in the 1930s. These were mighty steel "Windjammers" like the Sindia above and the Peking below. They were employed carrying nitrates and grain around the Horn ( Cape Horn ) from South America and Australia to Europe. The cost of fueling the steamships of the day for such long and difficult voyages gave the sailors one final advantage in economy, but eventually, this too ended. Today, a handful of these "Tall Ships" survive as museums and training ships.

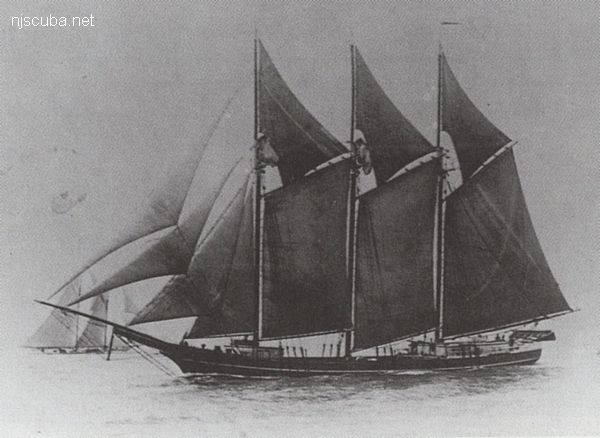

Schooners

A 4-masted schooner, fore-and-aft rigged on all masts. The origin of the word schooner is somewhat unclear. It may be derived from a Dutch word, or it could be related to the archaic verb schoon, which means to skip or glide across the water.

The schooner was the last development of the working sailing ship that truly was a sailing ship. Schooners were built of wood, and later sometimes iron, mostly in shipyards in New England, and especially Maine. Schooners employed a simpler suite of sails than the "square-riggers" of the prior era. This made them easier to handle, although somewhat slower. The fore-and-aft rig is also much more suited to sailing into the wind, which makes schooners far more useful for coastal and even inland routes than square-rigged sailing ships, which are more efficient on long down-wind ocean voyages.

The simplicity of the schooner's rigging allowed the crew to be reduced to an absolute minimum, sometimes "just a captain, a cook, and one sailor per mast". This greatly reduced operating costs. Schooners eventually grew in size to equal or surpass their square-rigged predecessors. Five-masted schooners were not uncommon, and a dozen six-masted and a single seven-masted vessel were constructed, although the largest examples proved unwieldy, with the sails and booms having grown to a size that was difficult and even dangerous for the crew to handle. As steamers became bigger, faster, and more efficient, the schooner too became obsolete. By the 1930s, most sailing ships of all kinds had been either scrapped or converted to schooner barges, and by the 1940s, these too were obsolete, and the steamship reigned supreme.

Warships

Sailing warships also evolved to a high degree before being replaced by steam. Huge ships-of-the-line mounted 70 to over 100 guns on two or three decks and were seen as the ultimate expression of sea power, although in reality, they were too ponderous and slow for most uses. Smaller frigates were fast and maneuverable and were used for everything from convoy escort to merchant raiding, coastal blockades, shore bombardment, reconnaissance, military transport, communications, and many other tasks. Frigates mounted 28-44 guns on a single gun deck. The frigate was the real backbone of the fleet, and frigate commands were often more sought-after than larger capital ships. Ships-of-the-line and frigates all carried similar rigs - that of a three-masted full-rigged ship. Smaller warships - corvettes and sloops - were usually two-masted. Steam power was added to sailing warships in the mid-1800s, at which time iron hulls also began to replace wood.

Regardless of the size of the combatants, the object of naval combat in the 1800s was simple - blow the other guy to bits at close range before he did the same to you. The wooden-hulled ships of the era were generally poorly protected from each-others weapons, and usually, two vessels would simply maul each other until one or the other finally surrendered. In a fight like this, accuracy mattered little; rate-of-fire was everything, and highly trained English gun crews could get off more shots per minute than any others, and seldom lost. American crews were often as good as British, but French and Spanish crews were notoriously poor, both in gunnery and seamanship. ( This is no slur, it is documented history - Britannia really did rule the waves. )

The loss of the Guerriere was a stunning blow to the Royal Navy, which was the finest in the world, and quite unused to losing. However, the Constitution and her sisters were built specifically to out-gun their British counterparts, and this duel proved not to be an isolated event. After several more such losses, the British Admiralty became so concerned that for a time the longstanding order to British naval commanders to engage all enemies ( or face automatic court martial ) was rescinded in the case of the new American frigates !

Eventually, one of the new Yankee 'super-frigates' was captured, and her revolutionary design was duplicated and improved upon by British shipwrights. The balance of power was never really in doubt though, since the Royal Navy was ten times the size of the infant American fleet, and enjoyed complete control of the seas, even with the occasional bloody nose from their upstart former colonies.

Another of the Constitution's exploits took place right off the New Jersey coast, when she was chased in slow motion by a British squadron that would surely have destroyed her. On a windless day, the American ship escaped her pursuers by 'kedging' - carrying a small anchor out ahead on a longboat and dropping it, then pulling the ship forward with the windlass.

Paradoxically, few wooden warships ever actually sank in battle, because it is in fact very difficult to completely sink a wooden ship. The inevitable result of such set-piece slugging matches was a terrible loss of life among the crews, and since the larger ship almost always won, it was not uncommon for a smaller vessel to simply surrender to a larger one without a shot being fired, unless it was fast enough to escape. Even in a fair fight, most of the time one of the combatants would ultimately end up surrendering, and being taken as a "prize" by the other. If not too damaged, the loser might even be incorporated into the winner's fleet. The English in particular prized captured French frigates, which they often considered to be of superior design to their own. The Guerriere above was one such vessel.

Steam engines began to be incorporated in sailing warships in the early 1800s. The huge and inefficient engines of this era were used mainly as auxiliaries on vessels that were primarily still wind-driven, but they were useful for movements in port, and maneuvering close to shore when the wind might not cooperate. Over time, as the engines advanced in technology and efficiency, they were relied on more and more, until eventually, they became the primary motive force. Even so, masts and sails were retained on warships for many years as a backup to the sometimes cranky engines. By the late 1800s, steam engines had become dependable enough that the sails were no longer necessary, and so the era of the sailing warship came to an end.

Tall Ships

A number of historic sailing vessels remain today, either as restorations or as new-built replicas. Here is a short list of "Tall Ships" in the region:

She currently resides, fully restored, at the South Street Seaport in New York.

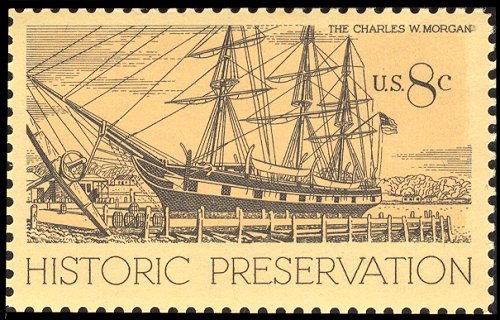

The Charles W. Morgan, the last remaining American sailing whaleship, on display afloat at Mystic Seaport, Connecticut. Launched in 1841, 106 x 28 feet, 313 tons. Just try to imagine spending years at sea on something that small. Or read about what it was actually like.

Museum Ships

The Biggest of the Big

A five-masted steel bark - the France was the largest sailing vessel ever constructed. 418 feet long, 6,200 tons. Launched in 1911, the vessel was wrecked in the South Pacific in 1922.

Another five-masted steel bark - the German R C Rickmers was the second largest sailing vessel ever constructed. 410 feet long, 5,548 tons. Launched in 1906, the vessel was sunk by a u-boat in 1917 after being confiscated by the British government during World War I.

The largest full-rigged ship ever constructed, and the only five-masted one ever, Preussen was launched in Germany in 1902. At 438 feet and 5,081 tons, her masts were three feet in diameter. She carried nitrates from South America until 1910 when a collision with a steamer in the English Channel left her aground and wrecked by a gale.

The largest schooner, the third-largest sailing ship, and the only seven-masted vessel of modern times, the American Thomas W Lawson was 404 feet long, 5,218 tons. Launched in 1902, the vessel was a disappointment to its designers, with very poor sailing qualities. Constructed as a sailing tanker, she spent most of her short life as a towed coal barge, before being lost in 1908 in a storm.

Modern Sailing Ships