Clam Dredges

A dredge is a vessel designed to remove sediment from the bottom, generally for the purpose of widening and deepening ship channels. However, the term is often applied to a specialized type of trawler. A clam dredge is a special type of trawler that takes clams from the sand. The device that actually does this is also called a dredge. Resembling a large steel cage, it is dragged across the sandy bottom, and rakes out the shellfish, along with rocks, debris, some bottom fish and lobsters, the occasional lost anchor, and anything else that is in its path.

Since clams live in the sediment and must be dug out, the clamming gear is large and heavy, requiring a large and powerful vessel to operate it. Larger vessels have an economic advantage over smaller ones, especially under present-day catch rules. The older, smaller independent clammers have all but died out, and the industry is now dominated by about 50 corporate fleet-owned vessels, some of which are of enormous proportions. ( All of the red boats in Point Pleasant are owned by Foxy-Kelleher Inc. of Cape May. )

Hydraulic dredging for surf clams began in the 1940s and reached its peak in the 1960s. It is still probably the most important local commercial fishery.

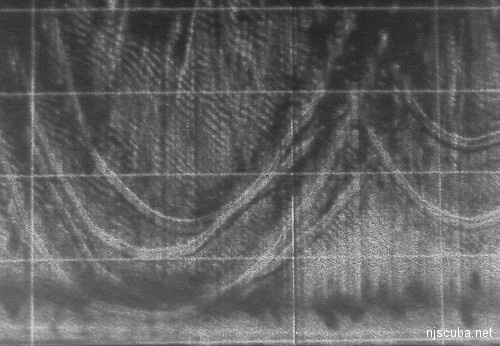

There must have been something especially good at this location to be worth dragging over it repeatedly in circles. In inshore areas and bays, dredging like this is extremely destructive of aquatic vegetation and shellfish beds, and is prohibited. It is estimated that the entire area of the Grand Banks is dragged over every year. This is a tremendous disturbance. New Jersey is probably similarly used.

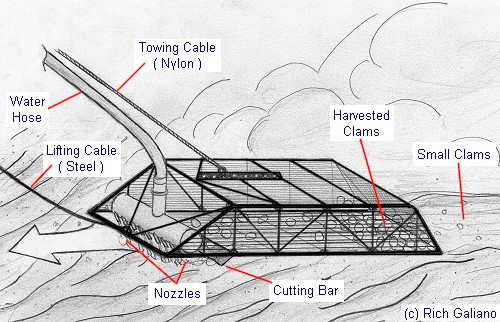

Dredge dimensions are approximately 6-9 feet wide by 18-20 feet long; each dredge is custom-made on-site as needed. Construction is welded steel. The dredge is raised and lowered on the steel cable, which is slackened when towing. The dredge is towed on a 3-4" nylon line; movement is in the direction of the arrow. The elasticity of the nylon prevents the whole towing apparatus from being destroyed should the dredge be hung up on an obstruction. The steel cable also serves as a backup should the nylon line part.

Water is pumped down from the boat through the 8" water hose into a manifold at the front of the dredge. Nozzles in the manifold direct water jets into the seafloor to break it up and raise out the clams, which are scooped into the dredge by the cutting bar underneath. Small clams fall through the measured gaps between the bars and are left behind. At intervals of 5-10 minutes, the dredge is brought up to check and empty if necessary.

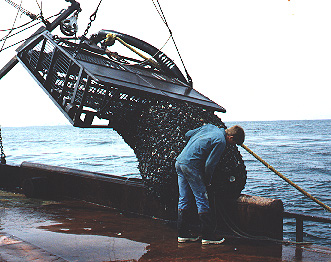

Once they are brought aboard, the clams are put into large wire mesh boxes known as cages. Each clam cage weighs several hundred pounds empty, and several thousand full. Every vessel is allowed to carry a certain safe number of cages, but the captains and owners sometimes think they know better, and load on extras. This, combined with the massive weight and high center of gravity of the stowed dredging rig itself, affects both the stability and buoyancy of the vessel and contributes to the high accident rate of these vessels.

Right - Empty clam cages on deck. In the background is the A-frame that raises and lowers the dredge.

Clams are very heavy - when full, the individual cages weigh thousands of pounds, requiring considerable port-side facilities for offloading and processing. Point Pleasant has one of the few clam processing plants in the state, and all the local clam boats tie up nearby, along with the occasional out-of-towner.

When such an overloaded vessel is caught out in heavy seas, it is at a much greater risk of capsizing or foundering. With too high a center of gravity, a vessel might not recover when rolled by a wave. Instead, it goes completely over and sinks. This is what may have happened to the Adriatic. An overloaded vessel might also sink under the extra weight of water from a wave breaking over the stern. This is exactly what the survivors of the Cape Fear described - instead of the water draining away, the back of the vessel simply kept going under and the ship sank. Another risk for any towing vessel is "tripping" - becoming somehow entangled in your own gear and capsizing. This is not an uncommon occurrence with tugboats, and may also have been the cause of the loss of the Adriatic. Of all the fishing vessels described here, clam dredges are by far the most common shipwrecks. Large powerful clam dredges have also been known to destroy old wooden shipwrecks outright - sometimes dragging right through and tearing them apart.

I am not aware of any environmental impact study ever being done on this, but anecdotal evidence suggests that the damage is great: high spots are pulled down, rock piles and shipwrecks are dispersed and buried, grass beds, structure, and habitat are destroyed, fishing grounds are ruined. It is a tribute to the resiliency of the bottom organisms that they survive at all.