Anchors & Chain

Anchors

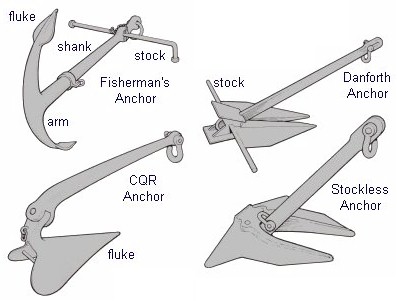

Not all artifacts are easily recoverable. Ship's anchors often weigh in the hundreds or thousands of pounds and require a well-planned expedition to bring back to shore. At right is an assortment of anchors, from the old-fashioned "Fisherman's" anchor of the 1800s to the modern stockless or "naval" anchor, and its small cousin, the Danforth anchor.

Chain Piles

Especially on older wrecks, anchors are often associated with large chain piles. After the hull rots away, the heavy chains fall in a heap to the bottom. Over time, rust and marine growth cement the loose links into a solid mass.

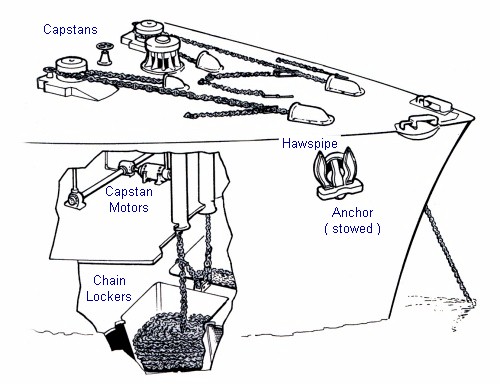

Although the diagram above depicts the bow of a modern vessel, old sailing vessels were generally similar, except that the capstans or winches were powered by steam engines, or even by manpower in very old ships. The anchor chain is drawn up through hawsepipes in the bow of the vessel, across the deck, and finally fed down into chain lockers in the bottom of the ship. Eventually, the shipwreck disintegrates, exposing a congealed mass of chain to mark the bow. Often, the associated capstans, winches, donkey boiler, and even the anchor itself are nearby.

At right, a stockless anchor drawn up into its hawsepipe, showing the handling advantages of this design over the old-style anchor below.

Anchor and chain on the "Big Hankins" wreck.