United States Coast Guard 3

Aids to Navigation

The US Coast Guard maintains a number of aids to navigation to assist vessels entering and leaving ports, both great ports like New York and Philadelphia, and minor ports like Shark River and Montauk. At sea, these aids take the form of buoys that mark out channels and shipping lanes.

Shipping lanes are like divided highways at sea. Inbound and outbound lanes are separated by a wide "Separation Zone, " which may or may not be depicted on the charts in this website, depending on the scale. Ships "drive on the right" just like cars in civilized countries. At the inbound end where all the lanes converge into the harbor channel, things get messy, and I didn't try to depict it. Likewise, the outer ends of the lanes are not exact either.

The lanes are marked by buoys at each end ( red crosses on the chart. ) All lanes into New York converge on the Ambrose Light Tower, which got knocked down so many times that the Coast Guard finally gave up and replaced it with a buoy. From there, the Ambrose Channel leads into New York Harbor. They are also minor lanes and channels around Sandy Hook ( not shown. )

The approaches to New York and Philadelphia are depicted:

- Ambrose - Nantucket

- Ambrose - Hudson Canyon

- Ambrose - Barnegat

- Cape Henlopen - Five Fathom Bank

- Cape Henlopen - Delaware

A number of enormous "can" buoys used to mark the ends of the shipping lanes. In New York waters, these were:

- A - entrance to Ambrose Channel

- BA - Barnegat - Ambrose

- NB - Nantucket - Ambrose

- B - Barnegat

- HA - Hudson Canyon

- NA - Nantucket

As far as I know, only the A buoy remains. Navigation buoys repeatedly get run-over, and have been made obsolete by radio navigation. The smaller inlets along the coast are marked with buoys as well, usually about one mile out.

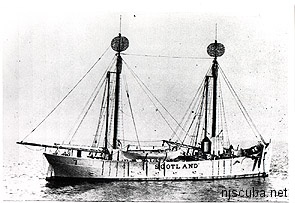

The Scotland Buoy marks a great shoal off Sandy Hook called the Outer Middle Ground. It is named for the steamship Scotland, which was damaged in a collision off Long Island in 1866 and then run aground off Sandy Hook in a vain attempt to save her. The vessel was subsequently torn apart by a gale and later dynamited flat. Originally a lightship was placed over the wreck, but eventually, that was replaced by an automated buoy, which is actually further out to sea than the original site. The triangle formed by the Scotland Buoy, the Ambrose Channel Buoy, and the Ambrose Light Tower is the area of highest congestion in the approaches to New York.

Ambrose Light Tower

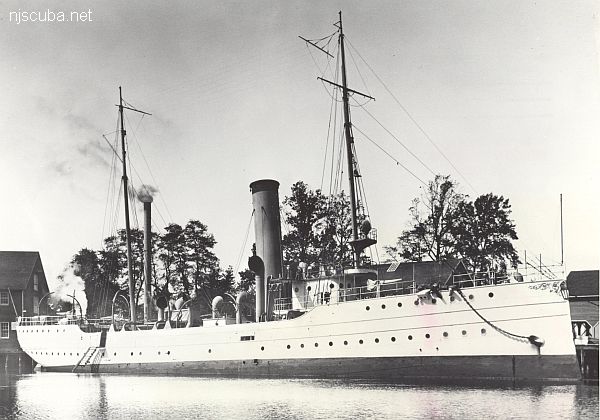

The old Ambrose Tower (above) went into operation on August 23, 1967, replacing the lightship that occupied that spot previously. It marked the convergence of the three main shipping lanes into New York. The old tower was made of prefabricated sections that were floated to the site on barges from Norfolk, Virginia. The Texas-tower structure was supported by a framework of four 42 inch diameter steel pipe legs, sunk 245 feet down to bedrock. Cross-braced with 18 and 20-inch diameter steel pipes, the structure was designed to withstand even the worst hurricane.

The station cost $2.4 million to build. The platform was two decks high. The lower deck housed the fuel and water tanks. The upper deck provided living quarters for the 6 permanently assigned Coast Guard members and had room for 3 transient members. Four crew members were on duty at all times. Crew members served two weeks on the platform before getting a week off. The roof of the platform served also as a heliport.

The main light tower jutted from the southeast corner of the platform roof. The focal plane of the light was about 136 feet above mean low water. The 10,000,000 candle-power light could be seen about 18 miles. The characteristic of the light was white group-flashing, with three flashes every seven and half seconds.

The crew was permanently removed from the station on March 15, 1988. In early October 1996, the 754-foot Bahamian-registered oil tanker Aegeo plowed into the Ambrose Light Tower, causing tens of thousands in damages. It was a crystal clear night when the FOC tanker hit the 13-story tower, whose light can be seen 18 miles away, but was apparently not functioning at the time. The tower stood on three legs, but was considered damaged beyond permanent repair. The Aegeo's captain was found to be at fault.

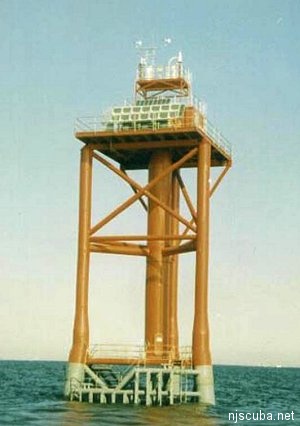

In September 1999, the old tower was taken down by the Army Corps of Engineers, and replaced with a new one ( at right. ) the new Ambrose Tower was equipped with a 60,000 candle power light 76 feet above mean sea level that was visible 18 nautical miles. It was solar-powered, and flashed white every five seconds.

The new light was located about 1.5 miles east of the old site, 7.4 miles east of Sandy Hook, and ostensibly out of harm's way. However, it has also been damaged several times in collisions. In January 2001, the 492-foot Maltese freighter M/V Kouros V struck the tower, shortly after repairs from a previous collision had been completed. The owners of the ship, which was also heavily damaged ( requiring dry-docking ) posted a $3 million bond for repairs to the tower, which remained in service. The tower was finally replaced by a buoy, which I am sure gets run over regularly.

These accidents are legally termed "allisions" rather than collisions since the tower was not actually moving.

Lighthouses

One of the Coast Guard's functions is to maintain aids to navigation, and foremost among these was once the lighthouse. Although their function was first replaced by radio navigation, Loran, and now GPS, these old beacons still stand along the shore, picturesque relics of a bygone era. Most are now lit only for old times sake, although a few are still used as active, if secondary, aids to navigation. From north to south, the major lighthouses are:

Sandy Hook

Off the tip of Sandy Hook, NJ, is the oldest working lighthouse in the country. It was designed and built in 1764 by Isaac Conro. The light was built to aid mariners entering the southern end of the New York harbor. It was originally called New York Lighthouse because it was funded through a New York Assembly lottery and a tax on all ships entering the Port of New York. Sandy Hook Light has endured the occupancy of British soldiers during the Revolutionary War and exposure to the elements at the end of Sandy Hook. The view of the New York skyline from the bridge crossing into the Hook illustrates the importance this light played in the history of New York harbor.

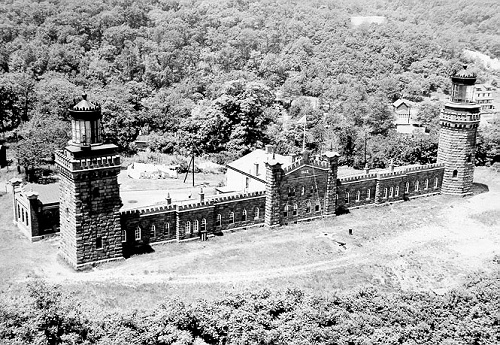

Twin Lights ( Navesink )

Situated 200 feet above sea level atop the Navesink Highlands, Twin Lights has stood as a sentinel over the treacherous coastal waters of northern New Jersey since 1828. Named Navesink Lightstation, it became known as the "Twin Lights of Highlands" to those who used its mighty beacons to navigate. As the primary seacoast light for New York Harbor, it was the best and brightest light on the Atlantic Coast for generations of seafarers. Many a life and cargo were saved by the sweep of its beacons.

The current lighthouse, built in 1862 of local brownstone, cost $74,000, and replaced the earlier buildings that had fallen into disrepair. Architect Joseph Lederle designed the new structure with two non-identical towers linked by keepers' quarters and storage rooms. This unique design made it easy to distinguish Twin Lights from other nearby lighthouses. At night, the two beacons, one flashing and the other fixed, provided another distinguishing characteristic.

With the development of automated lights, offshore light towers, radar, and other sophisticated navigational equipment in the 20th century, manned lighthouses gradually became obsolete. While there are still working lighthouses in the United States, many have been decommissioned - a fate that befell Twin Lights in 1949. After 121 years of service, the most powerful coastal light in America was extinguished.

The State of New Jersey acquired Twin Lights from the Borough of Highlands in 1962 and opened it as a museum. Today, visitors can tour the lighthouse, climb the North Tower for a breathtaking view of the Atlantic Ocean, visit the exhibit gallery, and see the 9-foot bivalve lens on display in the generator building. Twin Lights no longer guides ships into New York Harbor, but it stands as a formidable reminder of the important role lighthouses played in the maritime history of this country. Twin Lights is listed on the State and National Registers of Historic Places.

Barnegat

In June 1834, Congress appropriated $6,000 for the construction of a lighthouse at the north end of Long Beach Island. Work soon began on the 40-foot tower, and Barnegat Lighthouse was put into commission in 1835. Its non-flashing, fifth-class light was deemed inadequate by mariners of the day.

In 1855, Lt. George G. Meade, a government engineer, was assigned to design a new lighthouse. Meade, an 1835 West Point graduate, had recently designed Absecon Lighthouse, but he earned his place in history in the War between the States. Promoted to brigadier general, Meade defeated General Lee in the Battle of Gettysburg. Encroaching seas threatened the original lighthouse so its light was installed atop a temporary wooden tower in June 1857 and the original lighthouse fell into the sea later that year.

Meade submitted his construction plans in 1855 and construction began in late 1856. The new tower would be four times as tall as the previous one and cost about $40,000. It was built about 100 feet south of the original because erosion in the inlet remained a problem. The current lighthouse is really two towers in one. The exterior conical tower covers a cylindrical tower on the inside.

Barnegat Light, once the second tallest lighthouse in the United States, was commissioned on January 1, 1859. The tower light was 165 feet above sea level. It remained a first-class navigational light until August 1927, when the "Barnegat Lightship" was anchored 8 miles off the coast. The tower's light was reduced by over 80 percent, but it was not extinguished until January 1944.

The lightship was removed in 1965, made obsolete by electronic navigation. In 1988, the lighthouse was closed for repair; re-opening for visitors in 1991, Although its light no longer functions, the tower is flood-lit at night and continues to attract thousands of visitors every summer.

Absecon ( Atlantic City )

At 171 feet, the Absecon Lighthouse is the tallest lighthouse in New Jersey and the third tallest lighthouse in the U.S. Visitors willing to climb 228 steps up the restored lighthouse tower are greeted with a spectacular view of the Jersey Shore. Even those who prefer to keep their feet firmly planted on the ground find the Absecon Lighthouse a fascinating place to visit. During its construction period, which lasted from 1855 to 1857, the Absecon Lighthouse temporarily fell under the direction of Lieutenant George Meade, who would one day command Union forces at the Battle of Gettysburg. More than a century later, the Absecon Lighthouse had its name added to the National Register of Historic Places. The same first-order Fresnel lens used to light the way for mariners when the Absecon Lighthouse first opened is still in use today.

Cape May

The Cape May Lighthouse is a lighthouse located in New Jersey at the tip of Cape May, in the town of Cape May Point. It was built in 1859, was automated in 1946, and continues operation to this day. There are 199 steps to the top of the Lighthouse. The view from the top extends to Cape May City and Wildwood to the north, Cape May Point to the south, and, on a clear day, Cape Henlopen, Delaware, to the west.

The lighthouse is owned by the United States Coast Guard, which maintains it as an active assistant to maritime navigation. The Coast Guard leases the structure and the grounds ( but not the navigation equipment ) to the State of New Jersey which, in turn, sub-leases the structure and grounds to the Mid-Atlantic Center for the Arts (MAC). MAC raises funds for the restoration and upkeep of the structure and allows visitors to climb to the top. On the way, MAC has placed interpretive exhibits about the lighthouse's history, the lives of the former keepers, and other maritime history of the Jersey Cape.

Others

There are also a number of minor lighthouses along the shore, including Sea Girt, Tucker's Island, and Hereford. In Long Island, Montauk Light is historic and well known, as is Fire Island Light.

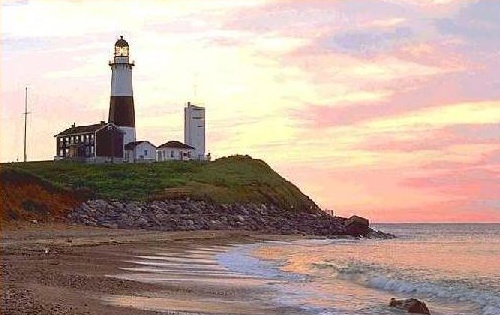

Montauk

The Montauk Point Lighthouse is in Montauk Point State Park, which is located in the village of Montauk at the eastern tip of Long Island in Suffolk County, New York. Montauk Point is the easternmost extremity of the South Fork of Long Island, and thus also of New York State.

Construction on the lighthouse was authorized by the Second United States Congress, under President George Washington in 1792. Construction began on June 7, 1796, and was completed on November 5, 1796. The lighthouse and adjacent Camp Hero were heavily fortified with huge guns during World War I and World War II. Those gun emplacements and concrete observation bunkers (which are also at nearby Shadmoor State Park) are still visible.

It was the first lighthouse in New York State and is the fourth-oldest active lighthouse in the United States. The tower is 110' 6" high. The current light, equivalent to 2,500,000 candle power, flashes every 5 seconds and can be seen at a distance of 18 nautical miles. The tower was originally all white. Its single brown stripe was added in 1900.

The United States Coast Guard considered tearing down the lighthouse in 1967 and replacing it with a steel tower further from the edge of the bluff. When the tower was built on Turtle Hill it was 300 feet from the edge of the cliff. It is now 100 feet away from the edge. After World War II the United States Army Corps of Engineers built a seawall at its base, but the erosion continued. In the wake of protests over the announced dismantling of the tower, Georgina Reid, a textile designer who had saved her Rocky Point, New York cottage from collapse by building a simple set of terraces in the gullies of the bluff, proposed to do the same at Montauk. Reid's concept Reed-Trench Terracing called for building the terrace platforms made of various beach debris - notably reeds. The practice (along with further strengthening of the rocks at the bluff toe) has appeared to have stemmed the erosion. She patented the process and wrote an article about it titled How to Hold up a Bank.

Fire Island

The Fire Island Lighthouse is a visible landmark on the Great South Bay, in southern Suffolk County, New York on the western end of Fire Island, a barrier island off the southern coast of Long Island. The Lighthouse is located within Fire Island National Seashore and just to the east of Robert Moses State Park. The current lighthouse is a 167 foot stone tower that began operation in 1858 to replace the 89-foot tower originally built in 1827. The United States Coast Guard decommissioned the light in 1974.

In 1982 the Fire Island Lighthouse Preservation Society (FILPS) was formed to preserve the lighthouse. FILPS raised over $1.2million to restore the tower and light. On May 25, 1986, the United States Coast Guard returned the Fire Island Lighthouse to an active aid to navigation. On February 22, 2006, the light became a private aid to navigation. It will continue to be on the nautical charts but will be operated and maintained by the Fire Island Lighthouse Preservation Society and not the USCG.

compiled from various sources