USS San Diego ACR-6 (2/3)

U.S.S. San Diego ( Armored Cruiser 6 )

reprinted from Wreck Valley III by Dan Berg

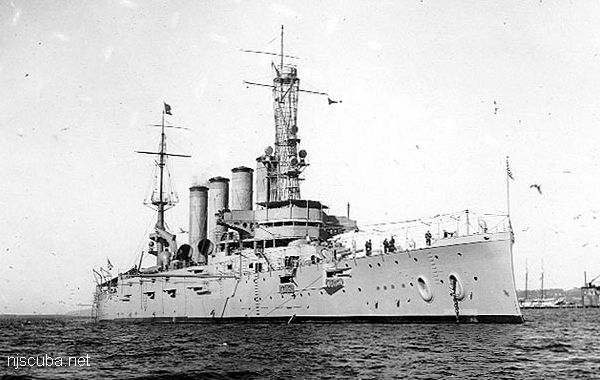

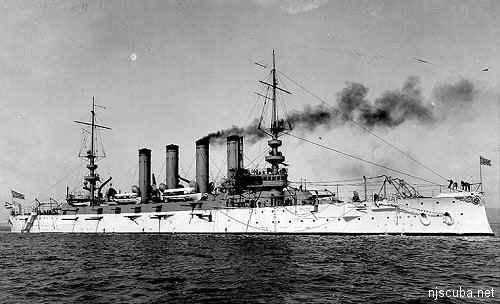

Originally launched as the California on April 28, 1904, by Union Iron Works in San Francisco, she was commissioned on August 1, 1907. She was 503 feet, 1 inch long by 69 feet, 7 inches wide, and had a displacement of 13,680 tons. She served as part of Theodore Roosevelt's Great White Fleet. Her twin props pushed her at a top speed of 22 knots. The warship's armament consisted of 18 three-inch guns, 14 six-inch guns both mounted in side turrets, four eight-inch guns, and two 18-inch torpedo tubes. On September 1, 1914, she was renamed San Diego and served as the flagship for our Pacific fleet. On July 18, 1917, she was ordered to the Atlantic to escort convoys through the dangerous first leg of their journey to Europe. The Diego held a perfect record, safely escorting all the ships she was assigned through the submarine-infested North Atlantic without mishaps.

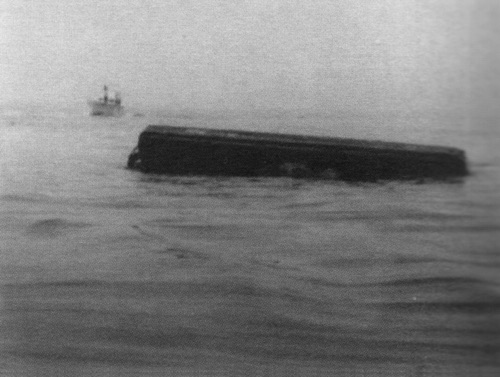

On July 8, 1918, the San Diego left Portsmouth, N.H., en route to New York. She had rounded Nantucket Light and was heading west. On July 19, 1918, she was zig-zagging as per war instructions on course to New York. Sea was smooth, the visibility six miles. At 11:23 a.m., an ear-shattering explosion tore a huge hole in her port side amidships. Captain Christy immediately sounded submarine defense quarters, which involves a general alarm and the closing of all watertight doors. Soon after, two more explosions ripped through her hull. These secondary explosions were determined later to be caused by the rupturing of one of her boilers and ignition of her magazine. The ship immediately started to list to port. Officers and crew quickly went to their stations. Guns were fired from all sides of the warship at anything that was taken for a possible periscope. Her port guns fired until they were awash. Her starboard guns fired until the list of the ship pointed them into the sky. Under the impression that a submarine was surely in the area, the men stayed at their posts until Captain Christy shouted the order "All hands abandon ship." In a last-ditch effort to save his ship, Captain H. Christy had steamed toward Fire Island Beach but never made it. At 11:51 a.m. the Diego sank, only 28 minutes after the initial explosion. In accordance with Navy tradition, Captain Christy was the last man to leave his ship. As the vessel was turning over, he made his way from the bridge down two ladders to the boat deck over the side to the armor belt, dropped four feet to the bilge keel, and finally jumped overboard from the docking keel which was then only eight feet from the water. As the Captain left his ship, men in the lifeboats cheered him and started to sing our National Anthem. Most survivors were picked up by nearby vessels, but at least four lifeboats full of men rowed ashore, three at Bellport and one near the Lone Hill Coast Guard Station. The San Diego was the only major warship lost by the United States in World War 1.

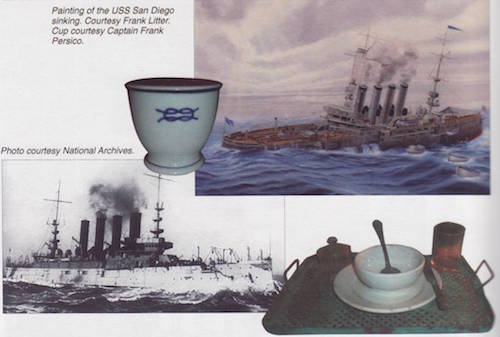

Please Note: It is no longer legal to recover artifacts from this wreck. The artifacts that appear in this text were recovered prior to the current law.

The original casualty reports ranged from 30 to 40. Apparently, the muster roll on the San Diego was not saved. The only list of men on board was the payroll of June 30, but since the end of June, they had received and transferred over 100 men. When the Navy eventually finalized the death toll, the official count was only six.

Since her sinking, there has been much debate about whether it was a torpedo, German mine, or U.S. mine that sent the cruiser to Davy Jones' Locker. Captain Christy wrote in his final log that they had been hit by a torpedo. The Navy, however, found and destroyed five or six German surface mines in the vicinity, so it is generally accepted that a mine laid by the U-156 did the job. Ironically, the U-156 was sunk on its homeward journey, possibly by a U.S. mine.

On July 26, 1918, the U.S.S. Passaic arrived over the wreck. Two divers were sent down to report on the condition of the San Diego. They reported the following: "Many loose rivets lying on the bottom ... Masts and smokestack are lying on the bottom under and on the starboard side of ship ... Ship lies heading about north depth of water over starboard bilge is 36 feet ... Air is still coming out of the ship from nearly bow to stern. It seems likely that as air escapes and she loses buoyancy, she may crush her superstructure and settle deeper." From this report, the Navy concluded that the vessel was not salvageable. As quoted from their letter to the Chief of Navy Operations, "In view of the reported condition and position of the San Diego, the Bureau is of the opinion that an attempt to salvage the vessel as a whole, or to recover any of the guns, would not be warranted." They did. however, have concerns about the site being a hazard to navigation and the possibility of dynamiting her to increase the available depth of water over the wreck. On October 15, the U.S.S. Resolute took another sounding on the site. It found that the wreck had settled slightly and now had 40 feet of water over her, so the wreck was not blown up.

In 1962, salvage rights to the San Diego were sold for $14,000. The salvage company planned to blow up the wreck for scrap metal. Several groups including the American Littoral Society, Marine Angling Club, and National Party Boat Owners Association banded together and lobbied. After a lot of bad publicity, public outcry, and financial compensation, the salvage company agreed to give up the job. The wreck, now an artificial reef, supports teeming amounts of aquatic life, not to mention many charter boat operations.

Another interesting side story to the Diego occurred when a Long Island diver attempted to raise the one remaining, 18-foot in diameter, 37,000-pound bronze propeller. He succeeded only in sinking his barge-mounted crane, which now rests on the bottom a short distance from the San Diego's stern. This barge has herself become a good lobstering dive. Someone else made off with the valued propeller.

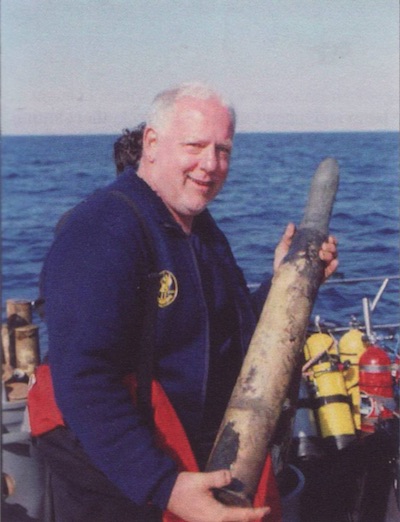

On June 3, 1982, the "New York Post" reported that the bomb squad had been tipped off that a local diver had recovered a two-foot-long, five-inch-diameter artillery shell from the San Diego. The diver had planned to blast it and stand it next to his fireplace. The shell was confiscated, but because it was too powerful for Suffolk's detonation site it had to be transported to Fort Dix, N.J. and was detonated by the Army. Lt. Thomas, commander of the Suffolk bomb squad, said, "It's the biggest warhead I've ever seen; it could go off just from drying out."

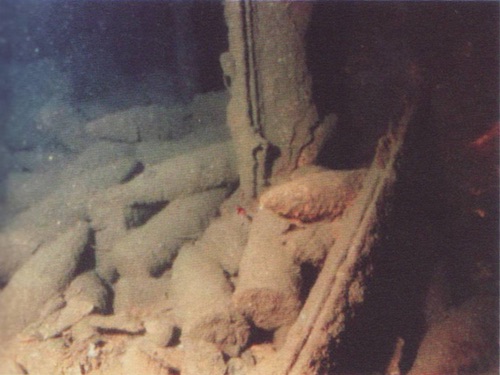

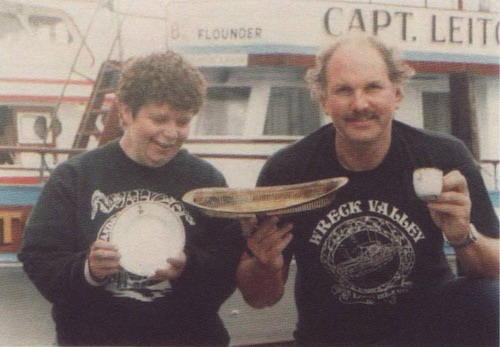

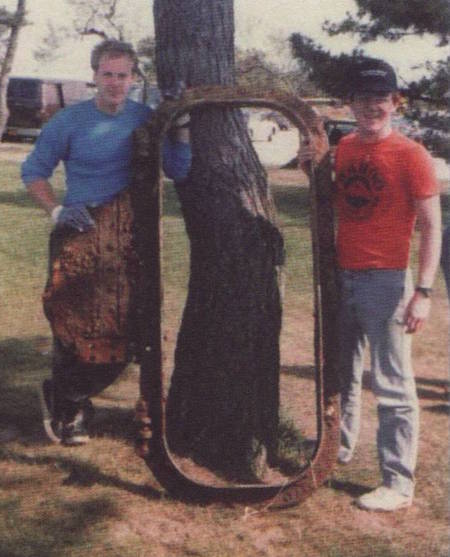

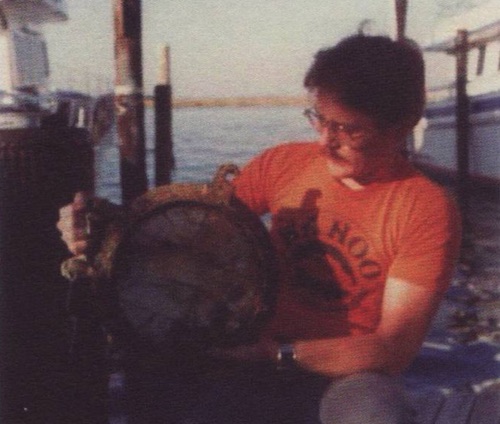

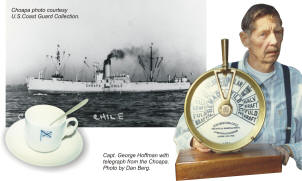

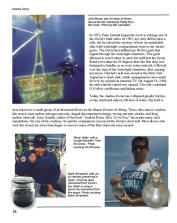

On October 8, 1987, the research vessel Wahoo, captained by Steve Bielenda, ran a special trip to the San Diego. Aboard were some of the East Coast's top wreck divers like Hank Keatts, Captain John Lachenmeyer. Hank Garvin, Janet Bieser, and myself. All participated in a dive to photograph, video, and recover artifacts from a newly discovered storage room that George Quirk had located in the bow of this World War I cruiser. John Lachenmeyer entered the water and secured the anchor line to the wreck. He was soon followed by Hank and I, who swam forward then dropped down the starboard side to the location of a small corroded hole in the outer hull. We penetrated to the interior of the wreck. Hank reached a small room and took some photographs. As he backed off I proceeded to video an intact supply room, full of china dishes, bowls, and silverware. This was to be the only view of the china room that day. Divers pulling artifacts from the silt-covered floor quickly reduced visibility to zero. As fresh teams of divers swam down to the wreck, lift bags popped to the surface carrying mesh bags filled with china, silverware, and even lanterns. Many of the artifacts recovered on this very successful day were donated to local museums, used to decorate area dive shops, or are incorporated into slideshows, television shows, and magazine articles, all aimed at increasing the public's interest in diving and shipwrecks.

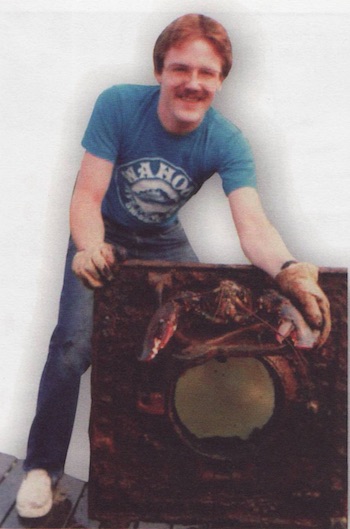

Today, the Diego lies upside down and relatively intact in 110 feet of water, 13.5 miles out of Fire Island In One of the nicest aspects of this wreck is that it can be enjoyed at various depths. Divers can reach her hull approximately 70 feet of water while her stern washout reaches a maximum depth of 116 feet of water. Besides supporting a huge array of fish life, she is one of Long Island's scuba diving hot spots. Divers have recovered artifacts such as bullets, portholes, cage lamps, china, and brass valves. The portholes found on the wreck are unique. They are made up of three parts, each of which is serial-numbered: the backing plate, which is bolted into her armor plating, a swingplate window, and a brass storm cover. What makes these portholes desirable to sport divers is the fact that the backing plates are almost impossible to unbolt while underwater This means that while many divers have swing plates or storm covers, very few have a complete set and even fewer have a set with matching serial numbers.

A few years back, Steve Bielenda and I were diving on the Diego. I swam inside a gun turret where I caught a five-pound lobster. When I turned around, I found a brass cage lamp and when I exited the wreck, there sit half-buried in the sand below me was an intact porthole. That was definitely one of my more productive dives. My next porthole from this wreck was not as easy and required approximately 15 working dives to recover. For the underwater photographer, this wreck provides structures, hallways, and compartments which all make for beautiful photos.

Wreck Valley III

Dan Berg has authored over a dozen books, hosted the Dive Wreck Valley cable TV series, and currently runs the Wreck Valley charter dive boat. My friends and I have been diving for artifacts and treasure for over 30 years.

The most comprehensive, accurate, illustrated collection of information, photographs, sketches, and stories ever written about the shipwrecks that lie off Long Island, New York and New Jersey.

The original Wreck Valley book was published back in 1986. At the time it was not only the first but the only book for area divers that detailed local shipwreck history and dive conditions. Capt. Dan's 2nd edition was printed in 1990 and became the most popular of his shipwreck publications. Wreck Valley III is a completely new update, expanded and enhanced edition of the Wreck Valley books.

Wreck Valley's 3rd edition covers the history, legend, present condition, aquatic life, and pertinent dive information on over 140 shipwrecks. This text includes over 550 illustrations, comprised of over 400 color photographs, 111 black and white historical photographs, 35 sketches, 20 side-scan sonar images, and nine 3D underwater shipwreck illustrations. Capt. Dan completely changed the book's format and design to accommodate all of the research and images collected in 30 years of local shipwreck diving. The collection of historical photographs alone would take years of archive research to locate and would cost a small fortune if purchased separately. Many of these rare images have never before been published.

Wreck Valley III includes a GPS list of accurate artificial reef and shipwreck locations. Divers, fishermen, marine historians, armchair sailors, or anyone with a general interest in history, diving, or the sea will surely find this book informative, fascinating, and the perfect addition to their library. Softcover, 8x10", 188 pages, printed in full color.