Lexington

- Type:

- steamer, USA

- Built:

- 1835, Jeremiah Simonson, New York NY USA

- Specs:

- ( 207 x 21 ft ) 488 gross tons, 165 passengers & crew

- Sunk:

- Monday January 13, 1840

fire - 4 survivors - Depth:

- 125 ft - 150 ft

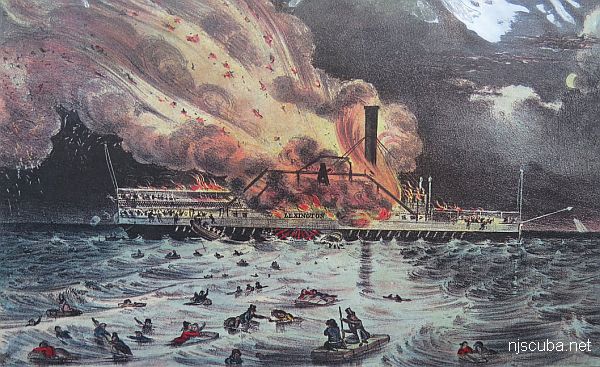

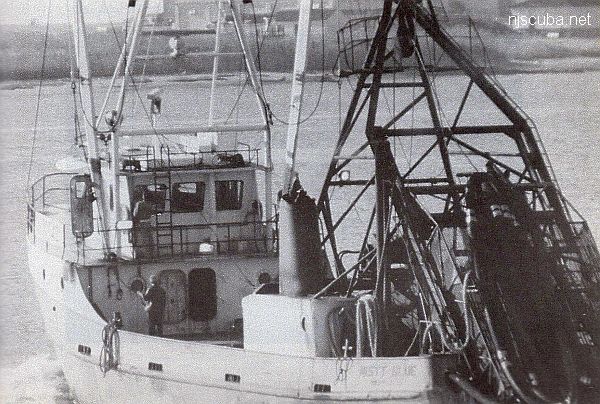

The Lexington burned and sank with a horrific loss of life. An almost successful attempt in 1842 to raise the wreck only resulted in the ship being broken apart and re-sunk in pieces. Much of the almost $20,000 in silver must still be scattered around the wreckage.

The Wreck of the Lexington

Long Island Sound's worst steamboat fire produces dramatic stories of survival

By Bill Bleyer

Staff Writer

Stephen Manchester stood at the wheel of the Lexington on a freezing winter night when the cry of "Fire!" sounded above the chuffing and clanking of the great steamboat. The pilot spun around and confronted flames spilling out from around the smokestack. Instinctively, Manchester cranked the wheel -- hoping to head the 205-foot wooden vessel to the Long Island shore -- four miles and more than 20 minutes away.

He was too late. Before the eastbound Lexington could complete the turn toward Eatons Neck, the tiller ropes burned through. The ship plowed on out of control at about 13 mph toward the northeast -- and disaster. Before the night of Jan. 13, 1840, was over, all but four of 143 passengers and crew aboard one of the era's premier steamboats would be dead. They would be victims of flames or bone-chilling water in Long Island Sound's first and worst steamboat fire. Ironically, the survivors owed their lives to the cargo of cotton bales that had fueled the fire but also served as makeshift rafts.

Despite a cold spell that left sheets of ice on the Sound and kept its competitors in port, the 5-year-old Lexington, pride of the Navigation Co.'s Stonington Line, had sailed at 4 p.m. from Manhattan. It was bound for Stonington, Conn., carrying 150 cotton bales, some of them stored near the smokestack. By the time dinner was served off Sands Point at 5:30 p.m., the temperature had plummeted to near zero and the wind was gusting.

When the alarm sounded two hours later, Capt. George Child sprinted to the freight deck, where the fire started. While some crew members worked to start a fire pump, the captain organized a bucket brigade. But the cotton-fed fire was already out of control, and Child shouted to passengers to take to the three lifeboats. But the flames kept crewmen from shutting down the boilers. As a result, the Lexington was still speeding through the waves and the lifeboats capsized as soon as they hit the water, throwing the occupants into the sea.

Chester Hilliard, a 24-year-old ship captain traveling as a passenger, also heard the shout of "Fire!" and ran out on deck. After waiting 15 minutes for the boilers to peter out, he led deckhands and passengers in throwing bales overboard to serve as rafts. Hilliard and ship's fireman Benjamin Cox nudged the last bale, about 4 feet long, 3 feet wide, and 18 inches thick, into the water and climbed onto it. It was about 8 p.m. Minutes later the center of the main deck collapsed, killing everyone there.

"We were sitting astride of the bale with our feet in the water, " Hilliard told the coroner's inquest a week later. "It was so cold as to make it necessary for me to exert myself to keep warm, which I did by whipping my hands and arms around my body. About four o'clock [in the morning], the bale capsized with us." Hilliard and Cox climbed back aboard but eventually, Cox could no longer hold on or even speak. "I rubbed him and beat his flesh, " Hilliard said. Then a large wave jarred the bale. "Cox slipped off and I saw him no more." About seven hours later, a Capt. Meeker of the sloop Merchant spotted Hilliard waving his hat and rescued him.

After Hilliard abandoned the Lexington, about 30 others remained on the bow with Manchester. The fire died down by 10:30 p.m. after consuming the center of the ship. Around midnight, Manchester was convinced the Lexington could not stay afloat much longer. The pilot joined two or three others on a makeshift wooden raft that immediately sank from their weight. Manchester climbed aboard a floating bale occupied by a man who gave his name as McKenny.

McKenny died about 3 a.m. That was about the time the Lexington should have arrived in Stonington. It was also when the hulk plunged 140 feet to the bottom northwest of Port Jefferson, carrying all those still aboard to their deaths. "My hands were then so frozen that I could not use them at all, " Manchester told the inquest. But when he saw the Merchant, he raised a handkerchief between his hands and Meeker plucked him off the bale. It was noon -- an hour after the Merchant had rescued Hilliard. Two hours later, Meeker spotted a third bale supporting fireman Charles Smith, who had escaped just before the ship sank.

The most amazing survival story was that of David Crowley, the mate, who went over the side with a bale of blazing cotton. He drifted for 43 hours after he left the Lexington, coming ashore nearly 50 miles to the east, at Baiting Hollow. He managed to stagger almost a mile to the nearest house and knock on the door before collapsing. Crowley kept the bale as a souvenir until the Civil War when he donated it to be used for Union uniforms.

The inquest jury lambasted the Lexington's owners and crew: "Had the buckets been manned at the commencement of the fire, it would have been immediately extinguished." the jury said that with better discipline, the lifeboats could have been launched successfully. And the jury condemned "The odious practice of carrying cotton ... on board of passenger boats, in a manner in which it shall be liable to take fire."

Despite those findings, "There didn't seem to be any response to it" by the government, said Edwin Dunbaugh, author of two books on Long Island Sound steamboats. It was not until the steamboat Henry Clay burned on the Hudson River a dozen years later that new safety regulations were imposed. The Lexington disaster proved to be a boon for Nathaniel Currier, a young man who made colored engravings. The New York Sun asked him to make an image of the fire for a special edition. It was one of the first illustrated news stories, and it made Currier famous.

-- Newsday Inc 2006

Questions or Inquiries?

Just want to say Hello? Sign the .