Lost At Sea (4/9)

Chopper Arrives at the Scene

Lt. Scott McFarland lowered the nose of the orange Coast Guard Dolphin helicopter and aimed at a flashing light on the black ocean below. The pilot and his crew had reached the last known location of the clam boat Beth Dee Bob, and the light held the promise of finding the boat's four crew members. It was 6:52 p.m. on Jan. 6, 1999, more than an hour since the first indication that the Beth Dee Bob was in trouble. McFarland knew there was little chance now of seeing the vessel. For several minutes, he had been following a signal from the boat's emergency position indicating radio beacon - or EPIRB - a device that under normal circumstances operates only after it has floated free from a sinking vessel.

Rescue swimmer Richard Gladish, 35, was perched in a jump seat on the right side of the chopper. He wore the dry suit, fins, mask and harness of his trade and was ready to work. The sliding door beside him was open, and the floodlights on the belly of the chopper were shining down on the churning sea from which the Beth Dee Bob had radioed at 5:40 that it was taking on water "big time."

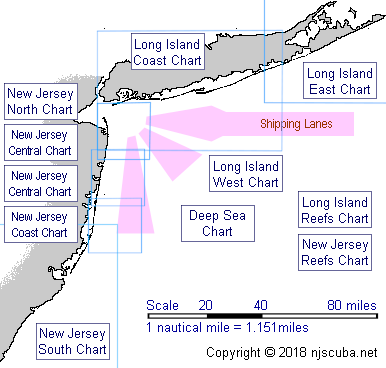

The EPIRB signal, relayed by satellite, had been received by the Coast Guard in Norfolk, Va., around 6 p.m. In minutes, McFarland and his crew, flying over the Atlantic on a training mission, were involved. The clam boat Danielle Maria had told the Coast Guard station in Point Pleasant that the Beth Dee Bob was taking on water. Commanders in Atlantic City, with scant information on the situation, ordered the Dolphin back to that base for a bailing pump before heading for the Beth Dee Bob. That decision cost precious minutes. It is about 60 miles from Atlantic City to the Mud Hole, the seamen's name for the notoriously turbulent section of water where the Beth Dee Bob had been stricken. Flying at 140 knots, the Dolphin would cover the distance in, at best, 25 minutes. But it flew several miles to its base, landed, and loaded a pump before it even began the trip.

If the clam boat was down, and if the crew members had managed to climb into their red neoprene survival suits, the four men could survive in these frigid winter waters without a life raft for up to 36 hours. If they had not been able to put on their suits, their lives could slip away in an hour or less.

McFarland passed by the flashing light and swung the chopper around to face into the nearly gale-force southwest wind. Hovering 100 feet above the 10-foot waves, the pilot and his crew could clearly see a man in the water. He was face down, his body tucked through the center of a life ring from which a strobe light flashed. "Rick!" McFarland called to Gladish. "Get ready!" Gladish reached up for the hook at the end of a cable descending from a small derrick mounted on the chopper's roof. He pulled the cable through the open door to attach its hook to the harness that crossed his chest. He signaled to McFarland. Ready!

The Dolphin was the second vessel committed by the Coast Guard to save the Beth Dee Bob's crew. A 41-foot boat that had left Manasquan Inlet in Point Pleasant just after 6 p.m. was also on its way. With the Dolphin reporting only one survivor in view, a broader search, perhaps for the rest of the crew in a life raft, was needed.

As the evening progressed and Wednesday became Thursday, more aircraft and boats would join in the rescue mission. At 7:05 p.m. Wednesday, a second aircraft would be dispatched from Atlantic City. A 47-foot boat would be sent from Barnegat Light, 30 miles to the south, at 7:38, and a 44-foot boat would leave Manasquan Inlet three minutes later. At 4:14 the next morning, the 82-foot cutter Point Highland would arrive from Cape May, and a C-130 aircraft would arrive from Elizabeth City, N.C., at 6:26 a.m.

The sea would grow so rough as the night wore on that the smaller Coast Guard boats would eventually return to their docks, some of their crew members violently seasick. The aircraft would fly through the night, one crew relieving another. On shore, other Coast Guard personnel would put into a computer information on winds and currents and create a plan for the search - a grid blanketing 2,200 square miles over which aircraft would fly in tight patterns for the next two days and across which Coast Guard and other vessels would prowl.

The clam dock in Point Pleasant - normally an overlooked collection of sheds and cranes where the seafood smells of the catch are often lost in the stink of idling marine diesels - was bustling within a couple of hours of the distress call from Edward McLaughlin, the Beth Dee Bob's captain. Television crews and newspaper reporters descended. Fishermen lingered, hoping for good news, and when that didn't come, they began to grieve.

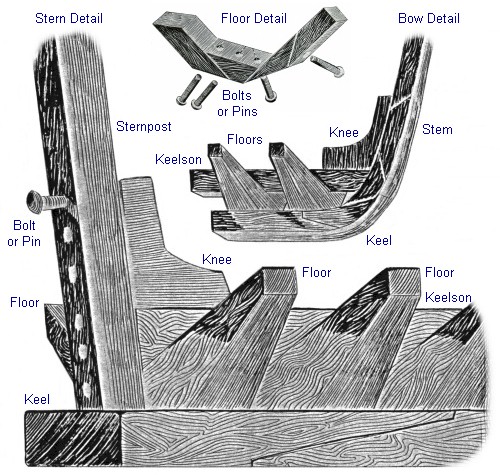

John Babbitt, 43, of Little Compton, R.I., earlier that day had been nine miles offshore on the 65-foot Ellie B, a wooden boat painted white and red and equipped with a side dredge. As captain, Babbitt had looked at the weather and decided to quit dredging surf clams. Steaming to the clam dock, he was about an hour and a half in front of the Beth Dee Bob, and he was already unloading his catch when the first word came about his friend, Ed McLaughlin, and his crew. Babbitt sat at the dock and cried a little. "With my buddy, Ed, you damn well know he died trying to fix that thing, " he would say later. "It's just sad. But it's just part of the gig."

Richard Hager, 66, was sitting on the couch in his second-floor garden apartment five miles to the west in Brick, tethered to an oxygen bottle to keep his diseased heart pumping, when, on the 10 p.m. news, he learned that the Beth Dee Bob had gone down. He had spent 30 years on fishing and clam boats. He knew the gig, knew what a sinking in January meant. Michael Hager, his 31-year-old son, the youngest of his six children, was supposed to be on the Beth Dee Bob.

Frightened, he phoned Michael's home a couple of miles away and got the answering machine. He called another son, Jeffrey, and asked him to drive to the docks to search for Michael's car. Jeffrey agreed, but instead, he drove to Michael's home and found his brother there. Michael had merely been at the 7-Eleven. About 10:30, Michael called his father, relieving Richard Hager's anxiety.

Michael had not shown up for an earlier trip aboard the Beth Dee Bob and was not invited back. Michael's own distress was to occur later, when, lying in bed thinking that he, too, could be lost at sea, he began shaking. At 12:45 a.m., he called his father once more. "I'm just so shook up, " he told his father. "Every time I think about it, I get chills down my spine."

The next day, he hugged his parents, and in the days that followed, he was torn by emotions. One moment, he was shouting with joy that his life had been spared and that his days with his son, Mikey, 5, were not over. The next, he wore the gaunt mask of the haunted, chain-smoked, and spoke in amazement of his good fortune. "Somebody must be up there, watching over me, " he told his mother, Judy, 64.

The news had traveled fast along the docks and across the airwaves. When Richard Hager saw the television report the night of Jan. 6, it had been only three hours since rescue swimmer Richard Gladish had crouched in the open helicopter door 100 feet above a frothing sea that was lit by the chopper's powerful flood lights.

As McFarland held the aircraft in a hover downwind from the floating man clinging to the life ring, Gladish, with the winch cable clipped to his harness, stepped out the door and began his descent. Once in the water, his way lit from above, he swam up the slopes of towering waves toward fisherman Jay Bjornestad. Kicking with his flippers, Gladish reached Bjornestad in a minute or two. The man's hands were wrapped around the life ring ropes, holding him into the ring.

Gladish lifted Bjornestad's head out of the water and talked to him. There was no response. The swimmer took off his neoprene gloves and checked Bjornestad's pulse. There was none. Nor could Gladish detect any breathing. Bjornestad's mouth was wide open, his jaw extended. His eyes were open and glazed over. His arms and legs were half frozen. Gladish waved in the helicopter.

McFarland held the chopper overhead as a metal mesh basket with cylindrical orange floats at either end was lowered on the cable. Gladish, with difficulty, managed to bend the stiffened man into the basket, which was then hoisted 100 feet into the chopper. The aircraft, low on fuel, banked west and sped toward a hospital on shore.

Gladish found himself bobbing in the dark, 12-foot seas. In the troughs, he could see nothing but blackness. In the instant when he rose to a crest, he could see oncoming lights, which disappeared as he fell to the next trough. He knew that the 41-foot Coast Guard boat was on its way, and he waited.