Redbird Subway Cars (3/3)

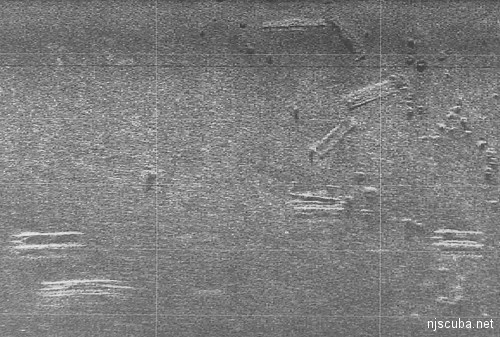

A string of Redbirds lying in the mud in the Garden State North Reef. Hard to make out much detail in this side-scan.

In 2007, I dove on some Redbirds again, this time on the Garden State North reef. This car, number unknown, was found at a depth of 85 feet, in the grouping nearest to the Fatuk. To me, it appeared to be completely intact. The only rust hole I found could be covered with your hand; damaged roof areas would have been caused by the crane at "launching", as seen in the pictures above.

Images courtesy Capt. Howard Rothweiler

As you can see, a few fish still hang around, but this car is no longer worth diving, or even fishing. This Redbird is much more deteriorated than the old Septa cars were at the same age. This is surprising, given that the Redbirds were built like tanks, as subway cars go, and were expected to last longer than the lightweight Septa cars.

So that concludes the story of the 'Redbirds Reef' - it is gone. These end caps will get knocked down in the next hurricane, and there will be nothing left. Does that mean the Redbirds were a failure? Not at all. These cars were sunk in 2003, and 13 years later there is still some small surface for encrusting growth and fish habitat. The cars were originally estimated to last 25-30 years, and although they fell far short of that, 10 years is still a useful lifespan for an artificial reef.

The likely cause of the premature demise of the Redbirds, and the even faster deterioration of the stainless steel Brightliners, is corrosion and failure of the fasteners. Rivets and weld seams often corrode much faster than the materials they are fastening. Once the fasteners go, the structure simply falls apart. I recall seeing white blooms of corrosion on the Redbirds just weeks after they were sunk. That was prophetic.

More-noble metals in contact with less-noble metals will cause them to corrode. This is accelerated in saltwater. The most noble metal is gold, which refuses to corrode no matter what (almost.) At the other end of the scale is zinc, which corrodes so readily that it is used to protect other metals as a 'sacrificial anode'.

Different types of steel rank differently on the nobility scale as well. The most obvious example is stainless steel, which is highly resistant to corrosion, although not immune. If the steel of the sheet metal was more noble than the steel of the rivets securing it, the comparatively tiny rivets would get eaten up very fast. This is probably what caused the stainless steel Brightliner to go to pieces within a year. Any copper components that remained on the cars would hasten the overall corrosion even more.

Any aluminum fasteners or other parts on the subway cars would have been devoured very quickly in saltwater by the galvanic reaction with the steel structure. Many owners of aluminum boats forbid pocket change on board - a copper penny dropped in the bilge will eat its way through the hull.

The USS Radford reef was a giant experiment in galvanic corrosion. The entire superstructure was aluminum, secured to the steel hull by clamps over the biggest o-ring I've ever seen. I looked at that, and thought "Uh-oh!" As long as the Navy took care of their ship, that worked fine, but once it was sunk in the ocean, the vessel quickly went to pieces. A badly-timed hurricane didn't help.

For everything you ever wanted to know about New York City subways, go to nycsubway.org.

Coda

Special thanks to Captain Jim Wilson of the Gypsy Blood for making an extra stop so I could buoy-dive the subway cars in the video.