Wooden Ship Construction (1/2)

Wooden ships have been constructed for thousands of years. Around the world, many different construction techniques have been used, some of them quite extraordinary. The ancient Greeks stitched the planks of their warships together edgewise to form an extremely light frameless load-bearing shell, much like a modern airplane fuselage. However, most wooden ships are built using a basic framing system that has changed little over the centuries.

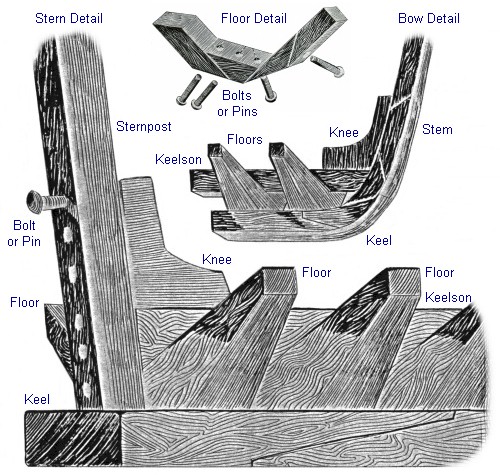

The illustration above shows most of the basic components of a wooden ship's frame. The keel is the backbone of the vessel. Attached transversely to the keel at regular intervals are angled assemblies known as "floors". The floors carry the vessel's ribs, shown below. The keelson is mounted atop the floors, sandwiching them into an extremely strong structure. The keelson provides additional strength and stiffness to the keel and floors. Below the keel, most vessels also have a "false keel" ( not shown. ) the false keel is generally not a load-bearing structure. Rather, its purpose is to protect the keel from wood-boring organisms and accidental groundings, and also to provide lateral resistance in the water so the ship will track straight in a crosswind.

The bow of a wooden vessel is built up around the curved stem, while the stern is built up around the sternpost. Assemblies that were either too large or too oddly shaped to be cut from a single piece of wood were built up using scarf joints - diagonal joints that spread stresses across a larger area than a simple butt joint. A scarf joint is apparent as the diagonal line in the keel above, and also in the assembly detail of the "floors." Especially high-stress areas, such as the bow and stern, are reinforced with large wooden "knees" and other reinforcing pieces ( not shown. ) the keelson also carried the lower ends of the masts in sailing vessels.

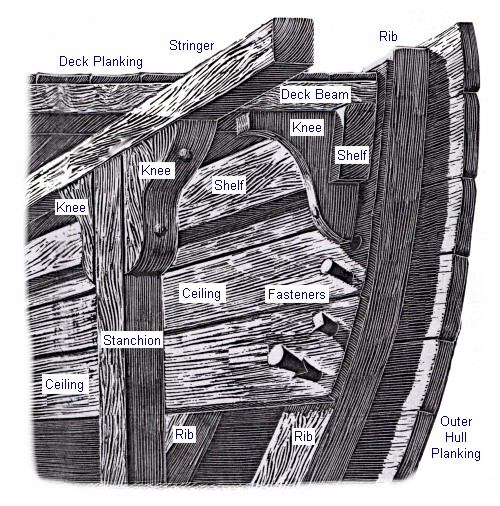

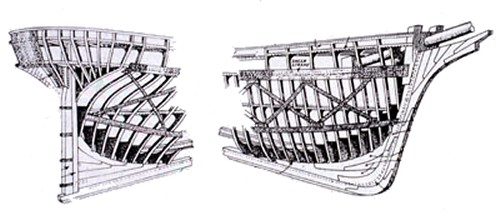

Below is a drawing of a typical wooden ship side and deck construction. The ribs are carried at their bases by the "floors". The outer surface of the vessel is sheathed with heavy wooden planking and waterproofed with caulk, a mixture of tar and hemp called "oakum". The inner surface of the vessel is covered with thinner planking known as "ceiling." A large longitudinal timber running around the inside of the hull called the "shelf" carries the transverse deck beams, which are supported along the centreline by stringers and stanchions extending upward from the keelson. Critical joints are reinforced with "hanging" knees, and the fasteners used are of similar materials to those described above, but smaller. Framing elements were usually of oak, while planking was more commonly pine.

On older vessels, wooden pins known as "treenails" were used instead of metal fasteners. This avoided galvanic corrosion of the fasteners. Corrosion of metal parts was a problem even in wood hulls. In a salt environment, different metals could react with both the wood and each other.

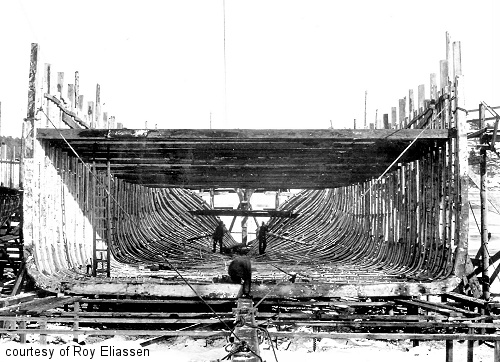

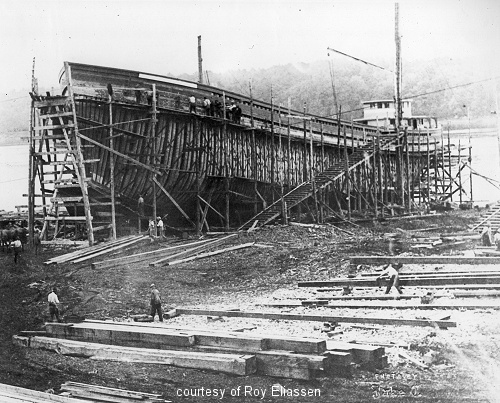

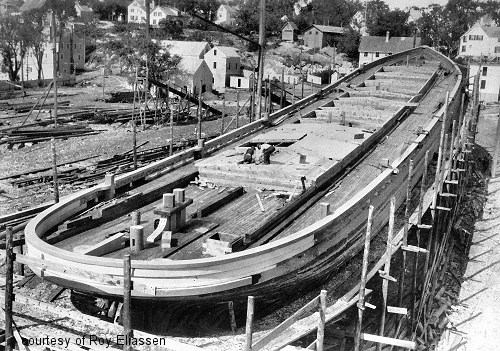

Wooden schooner barges take shape at a shipyard in Bath, Maine, circa 1916

See builder's specifications below.

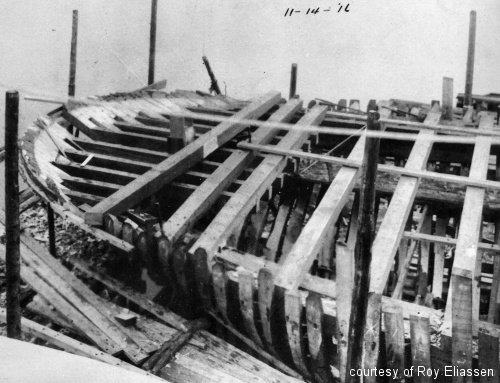

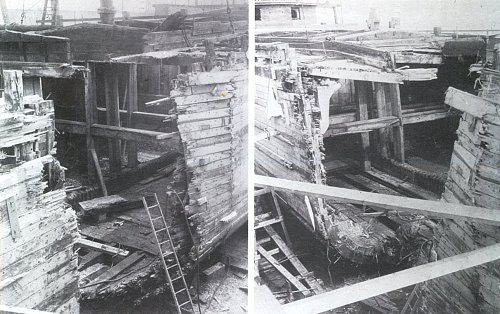

The structure of a wooden hull is shown to good effect in these images of a schooner barge after a collision. Notice that the interior decks have been removed to facilitate the loading of bulk cargoes from above. Fasteners, planking, ribs, ceiling, keelson, beams, stanchions, decks, hatches, and a mast are all plainly evident.

The fasteners used to attach all these various parts and joints have changed over time, from wooden pins called tree-nails initially, to iron bolts, and finally to copper pins. The largest pieces are secured with extremely large fasteners known as drift pins, up to several feet long, which were hammered into pre-drilled holes. Most of the wooden shipwrecks you will encounter while scuba diving are of an age where they will have metal fasteners.

Later wooden hulls were sheathed in copper sheeting, or covered with large-headed copper sheathing nails, to deter wood-boring marine organisms that would destroy the vessel. Not only sailing ships but also early wooden steamships were built along these lines, the only modification necessary being to accommodate the propeller in vessels so-equipped. The Delaware is a classic example. Modern wooden sailing yachts are still built using this same basic design.

After a wooden ship sinks, the hull begins to deteriorate. First, the masts are knocked down by the government, lest other ships collide with them. You hardly ever see a mast on a wooden shipwreck - they are either salvaged or simply float away. Light structures such as deck houses and hatch covers are quickly demolished by weather or float away, until only the sturdy hull remains, weighed down by ballast and cargo.

Over time, the weight causes the hull to sink down into the mud, and it fills with sediment. Eventually, the ribs weaken, and the sides are knocked down by storms. Waterlogged but not heavily ballasted, these usually lie like angel wings only slightly buried next to the main wreck, which eventually may sink so deep that only the lines of protruding stumps of broken ribs and planking mark the outline of the vessel. The bow and stern collapse, until finally the wreckage is flattened into a debris field.

Sometimes storms or currents scour out the insides of an old wooden wreck, and you can see the remaining structure, ballast stones, etc. Wrecks like this provide innumerable hiding places for marine life. Lobsters and fish will shelter in the gaps between the keel and keelson, as well as between the ribs and planking, and under the ballast stones. Lobsters will also dig their own holes under any overhanging pieces.