Atlantic Horseshoe Crab

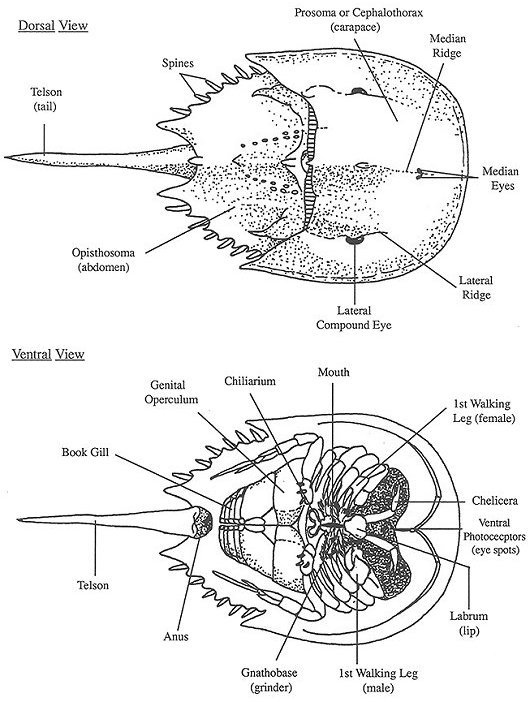

Horseshoe Crabs Limulus polyphemus are extremely common in the rivers and bays of this area. They are actually more closely related to spiders than to the other crustaceans on this page. In fact, technically they are not crustaceans at all. Despite their fierce-looking array of claws and spines, they are completely harmless.

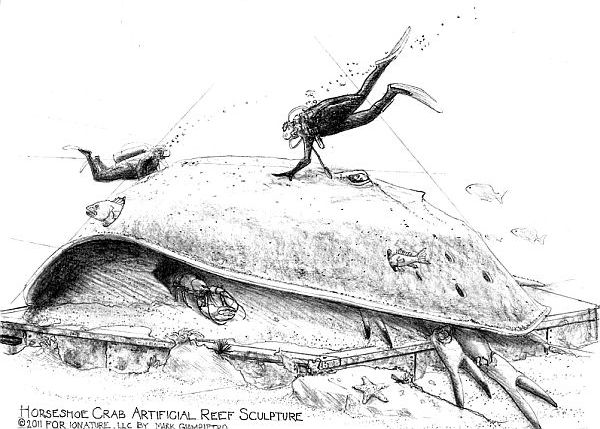

They are also completely inedible - not even the native Indians would eat them except in the direst emergency. They are nonetheless threatened by man since vast numbers are collected commercially for fertilizer, bait, and other uses. Horseshoe Crabs are found from the water's edge down to 75 feet.

Trail of the Horseshoe Crab

by J. Albert Starkey

The Horseshoe Crab, whose scientific name is Limulus polyphemus, has been crawling out of the water to deposit its eggs on the beaches for millions of years. This harmless creature is not really a crab but is more closely related to the spiders. It is sometimes referred to as a "living fossil" because it is believed to have existed in its present form for 175 to 200 million years.

Horseshoe Crabs are very temperature tolerant and so have been able to establish themselves in the coastal waters of North America from Maine to the Gulf of Mexico. They live on muddy or sandy shores below low-water level. Each crab, as it continues to grow, sheds its shell several times during its life. These cast-off shells may be seen on the beaches at any time of the year, frequently with various species of mollusks attached.

Following the reproductive pattern of countless generations, the Horseshoe Crabs come ashore in the bays and inlets of the New Jersey coast, in the Delaware Bay area they appear at the time of the full moon and accompanying spring tides of late May or early June. The warmer waters of late spring promote migration from the deeper waters to the land for their annual reproductive activities.

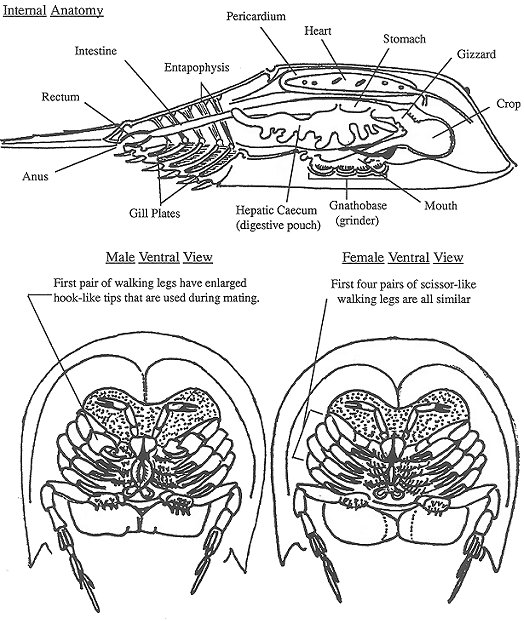

Millions of Horseshoe Crabs may be seen swimming onto the beaches with the high tide; the few days of higher tides at the time of the full moon permit the crabs to deposit their eggs farther up the beaches. Usually the female reaches the waterline attended by one or more males. The female is much larger than the male - very large individuals may measure 18 to 20 inches from the front of the shell to the tip of the tail. The successful male attaches himself to the shell of the female with the aid of two specialized claws which hook onto the rear edge of her shell.

The female scoops a shallow pit in the sand near the high-water line, where she deposits several hundred eggs on which the male releases his sperm. The quiet motion of the water carries sand into the pit and covers the eggs. The crabs return to deep water with the receding tide. The young crabs will emerge from the eggs in four to six weeks and spend their early lives in the shallow waters of the mudflats.

The eggs of horseshoe crabs are relished by gulls and shorebirds, who wait for enough morning light to dig them out and eat them. Many of the egg deposits do not become completely covered with sand, allowing the birds to find them easily. It formerly was a common practice for local farmers to scoop out the eggs and feed them to chickens and hogs.

Many adults do not succeed in returning to the deeper water. Some are inverted by wave action. Usually, a crab can easily right itself by vigorously thrashing its long tail. If this is not successful, the shell becomes full of sand and the crab succumbs to the hot sun on the drying beach. Others attempt to bury themselves in the sand of the beach but are not totally successful; they become tired and immobilized by the sand which dries about them and die before the next high tide.

Horseshoe Crabs were much more abundant years ago; the numbers reaching New Jersey's Delaware Bay shores are noticeably reduced in recent years. Studies being done along the Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia shores indicate somewhat lesser numbers there also.

Records as early as 1880 indicate that horseshoe crabs were collected yearly by the millions from the beaches of Cape May County. They were dumped into pens where they were allowed to dry completely, after which they were ground into fine particles and used for fertilizer. The last commercial operation of this kind closed in the 1950s.

Though no longer harvested commercially, the Horseshoe Crab today is serving man through important contributions to medical science. Its pale blue blood clots quickly when exposed to minute amounts of toxins that may contaminate certain medications, intravenous fluids, or blood components, and therefore can be used as a diagnostic tool in detecting such contaminants. The blood ( which is extracted without harming the crab ) also aids research in such diseases as spinal meningitis, cancer, and influenza.

A most interesting and helpful friend, the Horseshoe Crab and if we spare our tidal lands from development and pollution he will continue to leave his trail along our beaches for many more millions of years.

This article first appeared in New Jersey Outdoors - July / August 1977