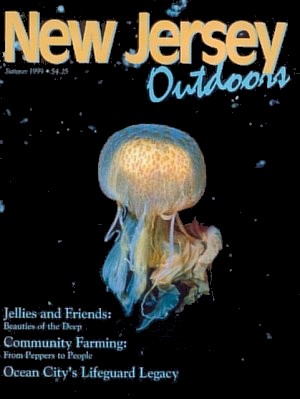

Jellyfishes

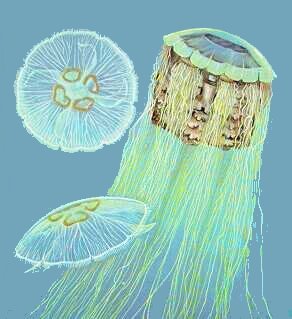

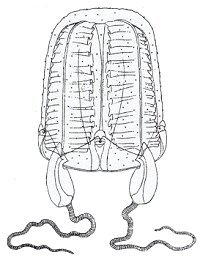

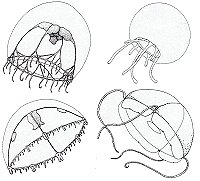

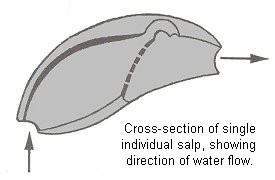

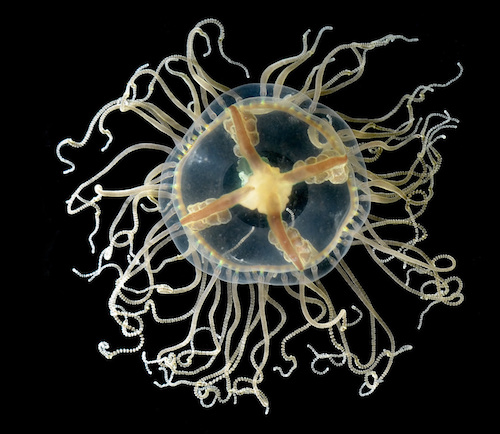

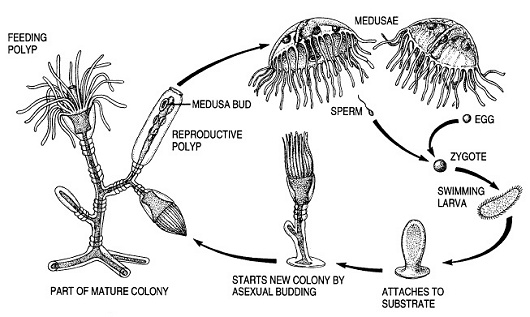

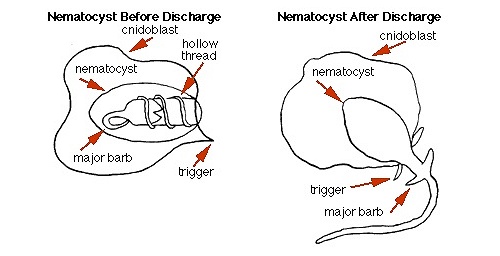

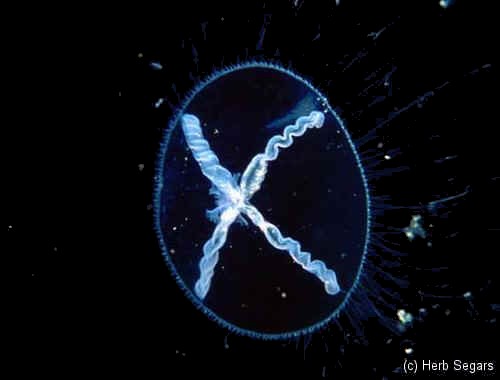

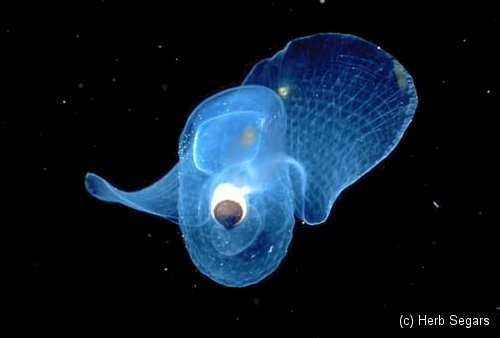

The many creatures on this page are lumped together for the one trait they all have in common - they are all "jelly-like" - soft, gelatinous, and more-or-less transparent. Other than that, they are for the most part completely unrelated. True Jellyfishes, Hydromedusae, and Siphonophores are in the phylum Cnidaria, related to bottom-dwelling Hydroids, Sea Anemones, and corals. Comb Jellies are in the phylum Ctenophora, and are completely unrelated to jellyfishes, as are Sea Butterflies and Corollas, which are mollusks. Salps are free-swimming tunicates, more closely related to us than to any of these other creatures.

Small harmless hydromedusae also appear sporadically in freshwater. There are also some types of freshwater jellyfish, but not around here. The rest of the ( non-cnidarian ) creatures on this page are unrelated, sharing only their drifting lifestyles.

Drifting In A Jellyfish Sea

Text and images by Herb Segars

It's late summer and I am 20 feet below the surface of the Atlantic Ocean off New Jersey. I am wearing long underwear, a waterproof ( and leak-proof, I hope ) rubber suit, 40 pounds of dive gear and a 30-pound weight belt to keep me from bobbing to the surface. A slight current forces me to grip the anchor line with one hand and take photographs with the other. I see a possible subject 6 feet away and watch as it drifts closer.

In the blink of an eye, I have set my focus and triggered the camera. The two underwater flashes attached to the camera fire and I hope that the results look as good as I envision. Between frames, I monitor my air supply and my time underwater. Thousands of planktonic subjects float by in the hour that I am below. Today turns out to he a good day - I run out of film before my time or air expires. Back on the boat, I dry off, change film and wait the required 1+ hours before making my next underwater photographic journey.

Capturing the underwater realm on film is a long and painstaking process. All my underwater work off New Jersey happens in the spring, summer and fall. In a good year, I am able to make 70 dives and shoot 70 rolls of film. When strong winds and rough seas bring a season of had weather, the number of dives and rolls of film taken drop to fewer than 20. In comparison, on a typical topside nature photography trip, I can shoot 70 rolls of film in a week.

This article first appeared in New Jersey Outdoors - Summer 1999