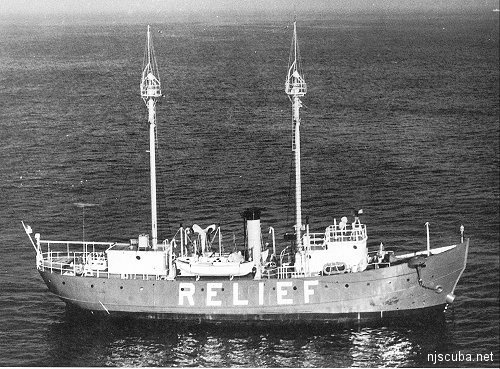

Relief Lightship WAL-505 (2/4)

by John Yurga

At the head of Ambrose Channel stands a large steel structure which resembles an offshore oil rig. This platform announces to approaching ships the location of the beginning of the 44' deep, 1000 foot wide channel, which was dredged for large ships entering the port of New York in 1908. The Ambrose Light Tower was completed in 1967, replacing the sentinels which had marked the channel for the previous 59 years. Those sentinels were Light Ships. Today, less than a mile from the Ambrose Light Tower lies the remains of one of these small but vitally important vessels whose purpose was to guide mariners safely to their destinations. She was run down by one of the very ships she was there to protect.

When the Ambrose Channel was completed, it represented a much faster and wider passage to New York and northern New Jersey ports than the Sandy Hook Channel. A lightship had been stationed at the entrance to the Sandy Hook Channel since 1823; it represented the earliest open-ocean lightship in America. On December 1, 1908, the Sandy Hook lightship was replaced with the vessel Ambrose, which lit the way into the new channel.

In the beginning of the 20th century, there were nearly 50 lightships stationed at various danger spots on our coasts. There were several spare ships whose duties were to maintain the station of a light vessel which needed to go into port for overhaul or to temporarily replace a vessel sunk by storm or collision. These vessels were called relief ships. The vessel lying in 110' of water off Ambrose light tower is one of these relief ships.

LV-78, this Relief Ship's official designation, was built in 1904 in Camden, NJ at the New York Shipbuilding Company. One of five sisters built at nearly the same time, she was built for nearly $1000 less than the $90,000 appropriated by the Department of Commerce for her construction. As completed, she was 129' long, with a width of 28'6" and a depth of 12'6". Her compound steam engine could move her through the water at 10 knots with her 7'9" diameter propeller. She was also rigged for auxiliary sail, as were many steam-powered vessels of her day. In appearance, she more resembled a bathtub than a ship. Her short stubby bow, combined with her large relative width, gave her a bowl-like look. This made her very seaworthy; an important factor in the face of what her duties were to be.

Lightships were anchored at all times at their designated locations. They had to be on station in fair weather or bad, on fine spring days and in the Nor'easters and hurricanes of the late year. Their presence was vital to the well-being of the ships that sought out these beacons to guide them safely on their way.

As a relief ship, LV-78 was assigned to the Third Lighthouse District, whose area of operation included New York and New Jersey. She made her way from one station to another, allowing permanent light ships to go into port for overhauls and upgrades. Over the years, she too was upgraded in performance.

When commissioned, LV-78 had a cluster of three oil-lens lanterns, which were raised to the masthead every night as a beacon. She had a 10' steam whistle, and a hand-operated, 3' diameter, 1000-pound bell. These last two items were used in fog and poor weather to assist ships in locating her position. It was not until 2 years later that a wireless unit was installed on the ship, and it not until 1917 did she have radio equipment installed. In 1922, she finally had a radio beacon installed, so ships could home in on her regularly transmitted signal. All this time, her main beacons were her lamps. The three oil lamps had to be lowered daily from the masthead to be refueled and to clean the black soot of smoky oil from the lenses. In 1926 LV-78 had her lamps replaced with electric lights, considerably easing the workload of the crew.

The relief ship's biggest changes occurred in the 1930s. During 1934-1935, she had her steam power plant removed and replaced with a 600-hp GM diesel engine, and all her auxiliary systems were converted to diesel as well. Her coal bunkers were rebuilt to contain the fuel for these engines. She was outfitted with a slightly smaller propeller, which could drive her at 8 knots. On July 1, 1939, she had a change of ownership, so to speak. The government organization that oversaw lighthouses and other aids to navigation was absorbed into the newly formed US Coast Guard. The name Relief remained painted in large white letters on her red hull, but her official designation was changed from LV-78 to WAL-505 under Coast Guard ownership.

World War II brought a change of duties for WAL-505. She became an examination vessel, boarding ships entering harbor for inspections. She carried no armament other than small arms for this duty. She was equipped with search radar in 1945.

With the end of the war, WAL-505 spent 2 years at the Scotland Lightship station off the New Jersey coast. In 1947, she regained her previous duties as a relief vessel in the Third Coast Guard District. In the next 10 years, she had her beacons upgraded to 1500-candlepower lamps with a range of 8 miles, received upgraded radar, and was equipped with a 17" air horn. Still, as a relief ship, her equipment was not as good as that of the vessels she replaced. For instance, Ambrose lightship had lamps with a 13-mile range, over a third brighter than the ship which relieved her for a month or so each year.

It was during this relief duty of the Ambrose that WAL-505 met her demise. Early in the morning of June 24, 1960, with Ambrose at St. George, Staten Island, for her annual overhaul, WAL-505 was stationed at the approach to Ambrose Channel. The relief ship was anchored with a 7500-pound mushroom anchor and had 600' of chain out. Twice a minute, she transmitted the call sign of the ship she had replaced. Due to the thick fog that morning, her foghorn was also blaring out the signal normally employed by the Ambrose.

The freighter Green Bay, owned by the Central Gulf Steamship Corporation, was outbound from New York at this time. The freighter was bound for Massawa, Eritrea, with general cargo. At 10,270 tons, the C-2 cargo ship dwarfed the 660-ton lightship, whose station was between the Green Bay and the open sea. Captain Thomas Mazzella of the Green Bay saw the image of the lightship on his radar and steered directly for it, thus keeping to the center of the deep channel. At what he thought was a distance of one and a half miles, he ordered a slight course change to go around the anchored lightship. He then went out to the bridge wing to watch for the fog-shrouded light to pass by off to the side. What he saw instead was the lightship suddenly materialize out of the foggy gloom directly ahead of his ship. Mazzella had misread his radar. He rushed back into the wheelhouse and ordered full astern on his engines, but it was too late. At 4:05 AM, the Green Bay struck WAL-505 at almost a 90-degree angle on the starboard side, just aft of amidships.

Aboard the diminutive lightship, Boatswain's Mate Bobby Pierce was alone on duty in the pilothouse. At about 4:03 AM, he heard the foghorn of the approaching freighter and saw the masthead light looming over his vessel. He sounded the general alarm, stirring his fellow crewmen from their bunks only seconds before the impact. When the Green Bay struck, the lightship rolled 15 degrees to port, then slowly righted herself. A triangular gash, 12' high and

ranging in width from nearly 2' to about 6", allowed water to pour into the stricken vessel at such a rate that there was no thought of trying to save the ship. As the collision had disabled WAL-505's lifeboat, the crew had to abandon ship into an inflatable life raft. They were able to do this without injury to any of the nine-man crew. As the ship began to go under, Chief Boatswain's Mate Joseph Tamalonis, commander of the lightship, ordered his crew to paddle away using their hands. The four oars were lashed down, and Tamalonis feared that the raft would be caught in the undertow if the men took the time to free them. WAL-505 disappeared less than 10 minutes after the collision. The crew then un-shipped the oars and rowed around in the thick fog for an hour before being picked up by a lifeboat from the Green Bay. The larger ship had only some slight damage to its forepeak from the collision, and had dropped anchor and launched a lifeboat to search for survivors from the lightship.

Soon afterward, the relief ship's crewmen were transferred to a 95' Coast Guard patrol boat and brought to St. George. There they found several crewmembers of the Ambrose working to get their vessel ready to return to station 2 weeks early. When the Ambrose crew saw Chief Boatswain's Mate Tamalonis, they yelled out to him "Come along, we need a chief!" Tamalonis replied, "I need a ship!".

Only 2 hours after the sinking of WAL-505, the Coast Guard cutter Yeaton was on station beside a buoy marking the resting place of the sunken vessel. The cutter's lights and foghorn served as a beacon for incoming and outgoing ships until Ambrose could get back on station later on in the day. Green Bay continued her interrupted voyage across the Atlantic, apparently unaffected by the collision. Navy divers visited the wreck of WAL-505 to ascertain the extent of the damage and the possibility of raising her.

Their report indicated that the necessary effort would not be cost-effective, and it was decided to knock down the sunken vessel's masts and superstructure using a wire drag.

Today, WAL-505, more commonly known as the Relief, rests on the muddy bottom at about 110 feet. The wire drag did its job well; the masts and much of the superstructure lie off the wreck to the port side. The hull of the ship sits upright, with the deck at a depth of about 90 feet. The hull remains intact, and one can drop off the starboard side amidships and find the triangular opening torn into the vessel by the Green Bay. Much of the wooden decking has been eaten away over the years, leaving only steel cross braces for a diver to contend with if he chooses to drop down into the crew deck. Two square hatches, one forward and one aft, allow even easier access to this deck, but can be difficult to find again from inside, as they are in the centerline of the wreck. Navigation is easiest along the hull. Almost all of the interior partitions are gone, with the exception of the engine room casing. This rectangular shape turns the inside of the wreck into a donut-shaped area. Forward are the winches used to raise anchor, and along the starboard side is the galley, where the stove is still visible. Crew bunks line both sides of the hull, while aft of the engine room casing are the officer's quarters and dining room. In years past, divers entered the engine room casing through doors on this deck, or through the now-missing engine room skylights. Another deck lies below, with the various artifacts one would expect to find in an engine room. Unfortunately, silt has filled much of the lower deck, denying access to that area. However, the crew deck, even after over 30 years of visits by divers, is still strewn with artifacts ranging from small arms ammunition and medicine bottles to cage lamps and the odd porthole or two.

In years long past, the 1000-pound bell and the 6000-pound light masts were recovered, but you may still manage to find a spoon in the galley debris or a whistle with the words 'USN 1944' on it. However, one of the most exciting things about diving this wreck is the opportunity to make a dry run before you even get wet!

At the South Street Seaport Museum in lower Manhattan, one of the museum's display ships is a virtual sister to the Relief. It is the Ambrose, one of several ships to bear that name. As you walk through this floating museum, you can get an idea of what you will see on the ocean floor. Take away the upper deck superstructure, masts, and rigging, and you will get an idea of what the Relief looks like. Mentally remove most of the portholes, for divers before you have gotten there first. Walk the crew deck, imagining what this area would look like with all of the thin steel walls gone. Note the location of the galley; it will be in the same place on the sunken Relief. Look up at the porthole and deadlights used as galley skylights, but don't make plans to recover a porthole nobody noticed; someone already did. Note the location of the square hatch behind the wheelhouse relative to the bell davit; will this be your entry point? Did anyone think to look for that cage lamp over the winch assembly in the bow? As you walk through the ship, you can come up with many ideas for what to do on your dive - probably enough to occupy several dives!

The Relief ship lies in an area of heavy traffic; care must be taken to avoid having your boat become a future destination of wreck divers. Visibility at the site varies greatly, depending on weather conditions and the tide. With clean incoming water, visibility can exceed 20 feet, but with conditions against you, you can be nearly blind on the bottom. Generally speaking, if you are planning to visit the interior of the wreck, you would be much better served on a good visibility day, when the green patches of light show the way back to the exit. If you choose to stay outside the wreck, check out the steering quadrant on the stern, or the bell davit forward of where the wheelhouse was. Inspect the tear in the side of the ship, look at the rounded bow, examine the machinery around the engine room casing topside as well, you get the picture. There is plenty to do anywhere on the wreck, especially if you have taken the time to acquaint yourself with the floating version of this ship first. The time it takes to make a visit to the Ambrose will be well rewarded when you reach the bottom.

Original NJScuba website by Tracy Baker Wagner 1994-1996