Stolt Dagali (4/4)

Chapter 31: Stolt Dagali

reprinted from Shipwrecks of New Jersey: North by Gary Gentile

| Built: | 1955 |

| Type of vessel: | M-class tanker |

| Previous names: | Dagali |

| Gross tonnage: | 12, 723 |

| Dimensions: | 582' x 70' x 30' |

| Power: | oil engine (diesel) |

| Builder: | Burmeister & Wain, Copenhagen, Denmark |

| Owner: | A/S Ocean (John P. Pedersen & Son, Managers) |

| Port of registry: | Oslo, Norway |

| Sunk: | November 26, 1964 |

| Cause of sinking: | Collision with SS Shalom |

| Depth: | 130 feet |

The 616 passengers and 450 crew members of the Israeli luxury liner Shalom had much to be thankful for on that cold, Thanksgiving Day morning: they all survived. At 2 A.M. most of them were asleep, dreaming of the forthcoming Caribbean cruise, and did not even feel the rending impact of the liner's stem as it sliced into the bowels of the Stolt Dagali. Nor were many awakened by the crash.

Not so lucky were some of the forty-three people aboard the Norwegian tanker. The Stolt Dagali left Philadelphia on November 25, 1964, with a load of edible oils and fats, and industrial solvents. She was on her way to Newark, New Jersey, in heavy rain and dense fog.

Both ships were equipped with radar and had their units switched on. Yet they still managed to find each other in the dark.

Said a Shalom passenger who wished to remain anonymous, "There was this terrific bang. I went to the porthole and I saw half of this ship beginning to slide away. It had a greenish striped stack." Celia Pearlman was taking a bath at the moment of impact: "There was this terrific crash and this can of hair spray flew over my head." She got out of the tub and picked up the can. Louis Ganz gathered Crackerjacks that spilled from an opened box. Aside from these comical interludes, the only injury occurred when crew member Marge Tostalisco was struck by a watertight door which bruised her ribs. Bleeding internally, she was later evacuated by helicopter and flown to Walston Hospital at Fort Dix.

The Shalom's sharp stem cut into the Stolt Dagali's port after tanks like a knife into butter. The charging liner then drove completely through the tanker on a diagonal from fore to aft, slicing the Stolt Dagali neatly in two. The forward section - comprising of about three-quarters of the tanker's length - remained afloat, buoyed by watertight cargo compartments. The stern section, containing the engine room and crew's quarters, sank almost immediately, dragged down by the weight of the machinery and the water that flooded the huge engine room.

Gone in an instant were the lives of eighteen men and one woman. One seaman was fortunate enough to have been sleeping, in a cabin which lay precisely where the ship was torn asunder - he awoke in the sea! One can only imagine the shock and disorientation he must have experienced when his pleasant, placid dreams turned into a stark and horrible nightmare as he was rudely thrown out of his dry, warm bunk into a bath of frigid water. Others were not so lucky: torn and twisted bodies littered the surface of the sea for miles - a ghastly human flotsam.

Despite the loss of her propulsion machinery and her primary generators, auxiliary generators provided emergency electricity, enabling the tanker to transmit a radio distress signal. "SOS. This is Stolt Dagali. Collided with unknown ship. Sinking repeat sinking." This and other messages from the Stolt Dagali fomented a flurry of activity. Nearby vessels altered course in order to converge on the site of the collision. The Coast Guard dispatched seven cutters and patrol boats, as well as a helicopter from the Floyd Bennett Field in Brooklyn. A Navy helicopter departed from Lakehurst, New Jersey.

Notwithstanding the rapid deployment of multiple rescue craft, the actual rescue of beleaguered personnel was initially delayed because the position that was given by the Shalom was fifteen to twenty miles north of the spot where the two ships had come together. First to arrive on the scene was the Santa Paula, a Grace Line cruise ship returning from the Caribbean under the command of Captain Theodore Thomson. "We had to circle around a wide area until we saw the Shalom standing still with her lights lit. Her bow was badly damaged. Then we saw the remains of the tanker, the bow section with some sort of a light lit, and we could see ten men aboard it." Captain Thomson positioned the Santa Paula so as to provide a windbreak for the Stolt Dagali's bow section.

The Coast Guard requested the Shalom to continue sending radio signals so that rescue craft could home in on her position. This proved to be an effective means of location. The Stolt Dagali soon reported, "Coast Guard helicopter and plane circling around us but has not sighted us." Visibility was half a mile. The Stolt Dagali also revised her original estimation of her condition: "Now not sinking immediately." Captain Kristian Bendiksen, master of the Stolt Dagali, was more concerned about the crew members on the separated stern section ( which no one at the time knew had already sunk ). Working on the premise that the stern was still afloat, he radioed, "My whole stern his disappeared." then, "thirty-three persons on after missing section."

Magnesium flares dropped by aircraft illuminated the area and presented an eerie sight for the crews. Navy helicopter pilot Lieutenant George Gilpin spotted a lifeboat, awash, with nine people aboard. "They were in all states of dress. Some just in their skivvies. They were elated when they saw us."

With his helicopter hovering above the sinking lifeboat, Gilpin lowered a cable to which was attached a "horsecollar ring, a large padded life ring." One at a time, he hauled men up into the belly of the chopper. He managed to recover four shivering seamen before a Coast Guard Cutter arrived, threw a net over the side, and scooped up the remaining five.

Two merchant ships arrived and stood by in case they were needed. These were the Reza Shah and the American Manufacturer.

As a result of the collision, the Shalom suffered a deep forty-foot gash in her bow. Captain Avner Freudenberg, master, soon determined that although there was some flooding in the forward compartments, his ship was not in immediate danger of sinking. He gave the order to man and launch a lifeboat in order to search for survivors from the vessel through which the Shalom had driven. Thirty-knot winds and twenty-foot seas hampered small boat operations. Nevertheless, the Shalom's lifeboat succeeded in plucking five of the Stolt Dagali's crew members from the water.

Captain Bendiksen was the last man to leave the Stolt Dagali's bow section. He heaped praise on his Coast Guard rescuers. "It was the best thing I saw in my life. The planes and the ships were there even though the sea was very rough and the fog very heavy." the survivors were taken to the Naval Air Hospital in Lakehurst, where they were treated for exposure and given heavy woolen shirts and denim pants. They were later transported to the Norwegian Seaman's House in Brooklyn.

With her bow low in the water, the Shalom returned to her berth at a speed of four knots. She was escorted by the Coast Guard cutter Spencer until they reached the safety of New York harbor. Captain Freudenberg was fearful that the Shalom's collision bulkhead might collapse if he proceeded any faster. A pair of tugs accompanied the liner after the Spencer turned back to sea.

After daybreak, the Coast Guard stepped up search and rescue operations, which continued all day. Five helicopters combed the sea in strictly regulated patterns. Initially, the flight crews were looking for survivors, but when it became apparent that the stern section had sunk and that no one else could possibly be alive, the mission became a body recovery operation. Thirteen bodies were picked up - by cutter and by helicopter - and were taken to Point Pleasant Hospital, where they were identified.

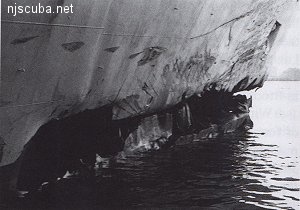

The Shalom's damaged bow.

( Official U.S. Coast Guard photo. )

By sunset, the Stolt's forward section had drifted fifteen to twenty miles north of the collision site. Throughout the day, the tug Cynthia Moran circled the Stolt's floating bow, trying unsuccessfully to get a tow line aboard. As one reporter described it, "The tanker was cut diagonally across, the cut from the starboard afterdeck slightly forward to the port side. The amputated end hung low in the water, rising and falling feebly. Each time it slapped downward, geysers shot upward. Nothing moved on the green deck, except the flooding sea. No flag flew"

After dark, the Coast Guard cutter Spencer patrolled around the aimless tanker in order to warn passing merchant ships of the menace to navigation. Searchlight beams stabbed at the deserted decks and superstructure, illuminating the floating wreck for all to see. Not until the following day was the Cynthia Moran able to take the Stolt Dagali in tow. The salvage tug Curb, of Merritt Chapman & Scott, provided escort. By that time, the sea was calm and the weather clear.

The ship's stability was so precarious that the Army Corps of Engineers withheld permission for the tug and tow to enter New York harbor. They were afraid that the tanker might sink and block the channel. The wallowing forward section was towed as far as Gravesend Bay, then moored.

The Zim Line, owner of the Shalom, was forced to return $300,000 to passengers whose vacations had been cut short. Meanwhile, the six-month-old $20 million-dollar luxury liner was undergoing inspection. "Using searchlights, surveyors entered the damaged area to photograph and measure it. At the same time, they investigated to determine if any of the hull's steel plates had been loosened by the impact of the collision. Divers were sent down to inspect the underwater portions to determine if there was any damage there."

On November 29, the Shalom was moved into the graving dock at the Todd Shipyard in Brooklyn. The Zim Line then entertained bids for repair of its famous flagship. The Shalom was soon moved to the Newport News Ship Building and Dry Dock Company, in Newport News, Virginia. Repairs took over a month and cost more than half a million dollars. The following two cruises had to be canceled.

The Shalom resumed her cruise schedule on January 5, 1965. Captain Avner Freudenberg was still in command. It is interesting to note that the Shalom was unique in that, except for special winter cruises, the Israeli liner's kitchens provided only kosher cuisine. " Shalom" is Hebrew for "peace".

Divers were called in to inspect the hull of the still-floating section of the Stolt Dagali. They determined that it was in no danger of sinking. Since a tanker is essentially a collection of watertight tanks that are held together by a hull, most of the tanks remained intact and their cargo unharmed. The Stolt Dagali was known as a parcel tanker, one that "specialized in carrying different types of liquid cargoes in specially coated tanks." the forward tanks - those in front of the midship superstructure - were filled with propylene tetramer ( a solvent ), methanol ( a wood alcohol ), and heptane ( a petroleum derivative ). Marine inspectors hypothesized that had the Stolt Dagali been struck by the Shalom in the tanks containing these volatile and inflammable liquids, sparks created by steel grating on ruptured steel may have ignited the spilling cargo and caused both vessels to burst into flame.

By offloading some of the cargo into small tank vessels, the Stolt Dagali's draft was reduced from forty feet to twenty-seven feet. "She was then moved three miles north to an anchorage off Bay Ridge, where she is to remain until five more tanks can be pumped out." After further lightering, the Stolt Dagali was moved to Pier 16 on Staten Island, where the rest of her cargo was removed and the truncated ship was laid up. On January 26, 1965, the forward section was moved to a dry dock at the Hoboken yard of the Bethlehem Steel Corporation.

In March 1965, the 440-foot-long forward section again went to sea. Not under her own power, of course, since her propulsion plant lay at the bottom of the ocean. Instead, she was towed across the broad Atlantic by a German tug that was bound for Goteborg, Sweden. The Stolt Dagali's forward section had been sold to C.T. Gogstad and Company of Oslo, Norway. That company's ship, the 18,880-ton Norwegian tanker C.T. Gogstad had broken in two after stranding off the Baltic coast of Sweden, a few weeks following the collision between the Shalom and the Stolt Dagali. The forward section of the C.T. Gogstad was pummeled to pieces, but the stern section with the propulsion plant was salvaged. The company was planning a marriage between the Stolt Dagali's bow and the C.T. Gogstad's stern - cargo tanks and engine - "till death do us part."

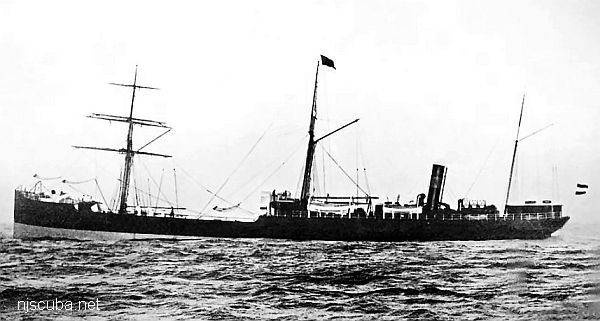

( Official U.S. Coast Guard photo. )

In May 1965 it was reported that "because of the similarity in vital statistics - only a one-foot difference in extreme width - ship-construction surgeons at the Eriksberg Shipyard at Goteborg were able to 'stitch' the two vessels together. Cargo tanks, cargo pipelines, and other gear - such as heating coils - were replaced, and the 'new' tanker is now being completed for service." the actual "stitching" took only one month to complete.

The new tank ship, grossing more than 19,000 tons, "will be operated on long-term charter in worldwide service by Parcel Tankers, Inc., the world's leading operator of highly specialized tank ships that move valuable high-grade liquid cargoes in quantities of up to 1,000 tons." She was christened the Stolt Lady.

There was rampant speculation about the cause of the collision. After a press conference at which a Zim Line spokesperson declined to permit Captain Freudenberg to answer penetrating questions, one reporter noted wryly that the captain stressed the fact that his radar unit was switched on, but "hie did not say whether it was being watched." Neither captain would admit as to whether fog horns had been blown or whistle signals exchanged. Nor would either one comment about the speed of his vessel at the time of the collision. Another searing concern was the Shalom's erroneous position report - had the bridge watch been so lax in navigation that they did not know the ship's location within fifteen to twenty miles?

All these issues and more would have been addressed at a Coast Guard inquiry, but the Coast Guard lacked jurisdiction. The collision occurred in international waters between two vessels flying the flags of foreign nations. Claims, suits, and countersuits were the province of insurance companies and the governments of the countries in which the vessels were registered. As expected, the owners of each ship alleged that the collision was solely the fault of the other ship. Accusations came fast and furious as attorneys for each side issued prepared statements which bolstered their client's position.

The Zim Line statement declared that the Shalom had not encountered fog until ninety seconds prior to the collision, until which time she experienced perfectly clear air. The opposition scoffed that the statement was "a futile attempt to justify the Shalom's admitted speed of more than 20 knots in dense fog." Ironically, the Shalom contended that the Stolt Dagali's speed of fifteen knots was excessive under the circumstances. The Stolt Dagali's representatives countered by contending that the tanker had reduced speed some twenty minutes prior to the collision, then had come to a dead stop at the approach of the Shalom.

The Shalom's second mate, Yehoshua Welt, later testified that the radar scope was cluttered with interference mixed with sea return ( the reflection of radar signals from wave tops ). He said he tried unsuccessfully for five minutes to clear up the interference by adjusting the radar set's controls. "It cleared a bit, but I couldn't get a perfect picture." Thus, he was not able to spot the radar blip that represented the Stolt Dagali until the two ships were less than two miles apart.

Weakening the case for the Shalom was the fact that the lookout was given permission to take a coffee break in the crew's mess shortly before the collision occurred. He returned to the bridge ", just as the collision was happening."

The aforementioned notwithstanding the Zim Line offered to reimburse the families of the Stolt Dagali's dead to the tune of $450,000 - this professedly because the company's investigation showed that "under Norwegian law, the Stolt Dagali is not liable to its crew members ... realizing that although recoveries cannot recompense the loss, but that recoveries by the families of the deceased may avoid hardship."

The Stolt Dagali's owners, A/S Ocean, stole a march on the Zim Line by having authorities in Goteborg, Sweden detain the Zim Line freighter Nahariyal when she docked. The Nahariyal was held for ransom until the Zim Line put up $1.5 million as bail. Attorneys representing the Stolt Dagali's interests claimed that the Zim Line's gracious offer to compensate families for their losses constituted all admission of guilt. A/S Ocean then filed a suit against the Zim Line in Sweden.

On January 3, 1965, an Israeli inquiry predictably absolved the Shalom of all blame for the collision and found her captain and crew innocent of charges of negligence. The Shalom subsequently filed a damage suit against A/S Ocean for $2.3 million in the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York. "The damage sought consisted of $1.9 million for the repair of the liner and the loss of profits while it was in a shipyard and $450,000 to meet the claims of the representatives of the crewmen who lost their lives." ( One of the lost crew members was a woman. )

Ordinarily, litigation between shipping companies was heard by the courts of the countries in which the interested companies were headquartered or maintained offices. However, in this case, or cases, two suits were filed in the United States: one a personal injury suit against both ship owners ( the shotgun approach ) by a passenger on the Shalom, and another co-filed by the Pacific Vegetable Oil Corporation and the Bunge Corporation, both of which sustained cargo losses and which filed libels against the Zim Line for reimbursement of their losses. Six months later, after the latter two companies paved the way through litigation, two other companies jumped on the bandwagon and filed suits against the Zim Line. These were the Cargill Company and the Unifood Company. Three months after that, Klockner and Company grabbed the bandwagon's tailgate and hitched its own suit for a free ride. All the food company suits were consolidated as a single libelant.

What followed was all extremely complicated proceeding, one with as many tangles as a dropped cat's cradle. As Federal Court Judge David Edelstein summarized it, "Many of the problems, in this case, arise because there are two main suits in two jurisdictions between the same parties to the same collision."

He went on to note that there was a "substantial difference in American admiralty law and the Brussels Collision Convention which is applied in Sweden. Counsel for all of the parties chose forums and maneuvered in a manner which best served their respective tactical positions. No element of fault or wrongdoing can fairly be attributed to any of the parties by reason of their choice of forums."

This statement underscores the evil essence of jurisprudence - that which is generally overlooked or ignored in the pious pursuit of moral judgment. Lawsuits are seldom filed in order to obtain justice; they are more often filed in order to obtain an opinion which is advantageous to the filing party.

Subsequent testimony contradicted earlier statements. Captain Bendiksen testified that he spotted the Shalom on radar at a distance of five miles, but took no immediate action because he was waiting to see how the Shalom intended to maneuver. For a long time, it seemed as if the Shalom did not intend to respond to the situation at all. When the liner was only half a mile away, a lookout on the Stolt Dagali heard a whistle signaling a turn to starboard, signifying that the Shalom intended to pass astern of the tanker. Bendiksen then ordered full speed ahead in order to charge in front of the liner's bow and increase the distance between the two ships. He was found at fault for failing to take radar fixes to determine the Shalom's speed and direction of travel when he had ample time and opportunity to do so.

Despite Captain Bendiksen's admission, the Zim Line sought to prove that the Stolt Dagali had been proceeding at excessive speed in fog prior to the collision. The company hired divers to photograph or recover the tanker's engine room telegraph and tachometer, expecting to find the telegraph needle showing full speed ahead and the tachometer registering one hundred rpm's.

Initially, the Zim Line divers were unable to settle the dispute because they claimed that a hole had been torched in the sunken tanker's hull and the instruments removed. "The prevalent opinion among well-informed shipping men is that a scavenging diver took the instruments for the brass value. However, some concede that the diver might have been hired by someone with an interest in the outcome of the damage suits. Waterfront experts point out that it is not unusual for independent divers to strip wrecks of brass, copper or silver, which is melted down and sold."

In fact, on December 1, 1964 ( only five days after the sinking ), a group of wreck-divers located the Stolt Dagali's sunken stern by following the oil slick. The first two down were Michael de Camp and Robin Palmer, followed shortly by James Caldwell, Jack Brewer, Jack Brown, and Russell Koch. They told newspaper reporters that they had entered the engine room and some of the passageways, "but did not find any of the six missing bodies." DeCamp took photographs of the wreck, Brewer shot movie film. It is unlikely that they would have made their actions public had they done anything illegal. Nor in the course of a single dive would they have had sufficient time to remove the instruments from the bowels of the engine room, even if they knew where to look for them.

It then developed that the diver later hired by the Zim Line to photograph or recover the instruments was the same James Caldwell mentioned in the previous paragraph. It was Caldwell's opinion that some other diver had entered the engineering quarters, and that "a room he saw in these quarters had been stripped clean of everything including furniture." Caldwell said, "It looked like a professional job by hard hat divers."

A/S Ocean claimed innocence and noted that the very facts that the Zim Line wanted to prove had already been admitted and that any evidence produced by the navigational instruments would merely bolster the Stolt Dagali's case by verifying Captain Bendiksen's belated attempt to take evasive action.

Caldwell eventually found the navigational instruments intact and bolted down precisely where they belonged. His photographs showed that in her final moments afloat, the Stolt Dagali's engine was set for full speed ahead. Zim Line attorneys showed the photographs to A/S Ocean attorneys, who shrugged at the confirmation of Captain Bendiksen's testimony. This part of the controversy eventually petered out. Perhaps it was never anything more than the lawyers' smoke and mirrors - or a legal red herring - intended to distract opposing counsel from more pertinent facts in the case.

The Zim Line finally agreed to settle the claims against it, at least as much as 90 percent of the losses. But it did not offer to settle until after it had forced its opponents' attorneys to expend 3,208 hours in preparing their case. These hours amounted to more than $125,000 in chargeable time. That did not include expenses for pretrial discovery, such as travel and lodging costs for the Stolt Dagali's crew, who were brought to the United States to be deposed in New York, where the first case originated. Only after causing this great expense did the Zim Line offer to discontinue the suit "without prejudice."

A ruling without prejudice meant that the Zim Line could sue again. As the judge noted, "The danger of harassment and 'repeated and vexatious suits' is thereby usually inherent." Furthermore, the Zim Line did not believe that it should have to pay its opponents' costs. Judge Edelstein denied the motion to discontinue "where the trial date had been fixed and postponed repeatedly at the behest of the libelant, all parties were in court ready to proceed, extensive pretrial investigation and depositions had been taken, over 200 exhibits had been marked in evidence, expert opinion on foreign law had been obtained, and documents had been translated. Proceedings had progressed too far to allow libelant to dismiss without prejudice and with the payment only of statutory costs."

In Sweden, on the other hand, the Zim Line was being forced to defend itself against A/S Ocean. After further convoluted legal logic, the judge permitted the Zim Line to discontinue the case in New York as long as it agreed to several stipulations: that no other claims be filed except for the case that was pending in Sweden, that the depositions and documents already marked in evidence be introduced as evidence in the case that was pending in Sweden, and that Zim pay $2,485.05 in court costs. Reimbursement for attorneys' fees and evidentiary costs was disallowed because it would have cost A/S Ocean an equivalent amount to prosecute the case that it initiated in Sweden when it arrested the Nahariya.

Eventually, the Zim Line paid 90 percent of the claims. A/S Ocean paid 10 percent of the claims for contributory negligence.

The Stolt Dagali's sunken stern quickly became a main attraction for wreck divers. Mike de Camp and his wreck-diving friends made several return trips after their initial exploration. On one of these trips, de Camp peered into a porthole and saw the body of the stewardess pinned to the overhead by the buoyancy of her life vest. He reported this gruesome find to the Norwegian embassy. The Norwegians were extremely thankful for the information, so much so that they asked if it was possible to recover the body and to look for others that might still be trapped inside. DeCamp said it was possible.

He then organized a body recovery operation. The group worked in turns to open the jammed door to the laundry room with a crowbar, then to drag the body through the passageways to a door leading outside the wreck. This difficult chore took place nearly a month after the sinking, by which time the body was not a pretty sight. The feet and face were, one, and loose flesh sloughed off against the divers' wetsuits as they squeezed the body through the doorway, brought it to the surface, and placed it in a body hag provided by the Norwegian embassy. An undertaker took charge of the body at the dock. No other bodies were located.

The Stolt Dagali is no longer a tomb. Her engine has been forever silenced, her drive train has been stilled. But three and a half decades of marine growth have converted the wreck to a high profile reef that is Magnificently encrusted with large sea anemones and other marine fouling organisms, providing a substrate that attracts large numbers of pelagic fish ( those that live at the top of the food chain ).

The stern section is one-hundred-forty feet long. Lying on its starboard side at a depth of 130 feet, it rises as high as 65 feet from the surface. The 'S' painted on the stack, once photographed by Mike de Camp, was no longer visible when I first dived the wreck in the 1970s. This was because of marine encrustation. Swimming into the stack was like entering the maw of a huge, dark cavern. Now the stack is gone.

The wreck offers the ultimate in penetration diving, with doorways leading to large, wide corridors, and ample light piercing two deck levels through double rows of portholes. Inside, the partitions have given way, leaving unblocked long passageways full of debris, broken furniture, ship's appliances, and personal effects. Divers should be aware, however, that the right-angle list is quite disorienting: the decks and overheads are vertical, the bulkheads are horizontal, and the stairwells on their sides. The stairs are now collapsed. Beware that large cavities in the decks make it possible to switch levels unknowingly, especially during a silt-out.

One can enter the engine room through the gaping skylights then descend past ghostly catwalks and railings all the way down to the massive rocker arms and the bedplates below. The room is as large as a small house. Although comforting ambient light fills the vast central portion, and all but the darkest of corners filled with piping and machinery, one can easily get disoriented in the compartment's immensity by straying into the shadows and cubbyholes.

Safer to explore is the chief engineer's office, which occupies the superstructure house, because the roof has rusted away. An outside companionway goes completely around the perimeter, with the portion on the sand appearing like a long black tunnel. Doorways and rust holes permit access to the interior from inside the companionway.

Large lobsters are found on the bottom, under the giant propeller, in the scattered wreckage, and also inside. But one should be careful picking up crustaceans from the deep interior, because rusting metal and rotting wood have left thick layers of silt which is easily disturbed. The act of grabbing a bug and stuffing it into a bag often causes one to muck up the companionways with horrifying, and possibly disastrous, results.

Alan Ferry found this out when he got turned around in a room, could not relocate the door, and was forced to doff his tanks and drop his weight belt in order to squeeze through a porthole and make a fast, free ascent to the surface. Others might not be so bold and clearheaded - or so lucky.

A great deal of the wreck's exterior has changed since the original edition of Shipwrecks of New Jersey. The superstructure is still largely intact, and the hull has so far retained most of its integrity. But the steel plates are pockmarked with giant rust holes, as if basketballs were thrown completely through the metal. In places, jagged perforations are stitched together to form large, amorphous openings, some big enough to swim through. Alan Ferry take note.

Additional deterioration has occurred inside, where the steel plates that form the partitions are thinner than the steel plates of which the hull and bulkheads are made. These interior changes are subtle, however, rather than massive: rust holes, fallen partitions, and the like. Continue to exercise caution.

For the underwater photographer, the Stolt Dagali is a dream site. Ambient light visibility often ranges between fifty and one hundred feet, sometimes more. The intact hull offers a great silhouette for available light photos because the wreck reaches so close to the surface and because it lies in a commonly clean area. The outer hull is painted with large sea anemones which, when feeding, extend a multitude of tentacles and give the appearance of a flowing flower garden. This is a perfect setting for macro and close-up photography.

Cod and Pollock are often found swimming around the wreck. Large Tautog and Black Sea Bass are the delight of spearfishing advocates. Ling live on the bottom and inside. Lobsters live everywhere. Bottom dwellers may be found in the debris field formed by machinery that has fallen off the upper deck.

Relic hunters still bring out mementos: portholes, brass engine parts and accessories, personal belongings, galley dinnerware stenciled with the shipping line's flag and crest, and other odds and ends. And, because the high side of the wreck is so shallow, even the novice wreck diver can see how a shipwreck should look.

The Stolt is a wreck for everyone.

GARY GENTILE'S POPULAR DIVE GUIDE SERIES

Shipwrecks of New Jersey: North

As suggested by the title and series name, this volume covers the most well-known wrecks sunk off the northern geographical coast of New Jersey: from Sandy Hook to Manasquan Inlet.

For each of the wrecks covered, a statistical sidebar provides basic information such as the dates of construction and loss, previous names ( if any ), tonnage and dimensions, builder and owner ( at time of loss ), port of registry, type of vessel and how propelled, cause of sinking, location ( loran coordinates if known ), and depth. In most cases, a historical photograph or illustration of the ship leads the text. Throughout the book is scattered a selection of color underwater photographs, some of the wrecks, more often of typical marine life found in the area.

Each volume is full of fascinating narratives of triumph and tragedy, of heroism and disgrace, of human nature at its best and its basest. These books are not about wood and steel, but about flesh and blood, for every shipwreck saga is a human story. Ships may founder, run aground, burn, collide with other vessels, or be torpedoed by a German U-boat. In every case, however, what is emphatically important is what happened to the people who became victims of casualty: how they survived, how they died.

Also included are descriptions of the wrecks as they appear on the bottom.

At the end of each volume is a bibliography of suggested reading, and a list of more than 400 loran numbers of wrecks in and adjacent to the area covered. Wrecks covered in Shipwrecks of New Jersey: North are: Adonis, Alvena, Antioch, Arundo, Ayuruoca, Balaena, Brunette, Catamount, Choapa, Coastwise, Continent, Daghestan, Delaware, Ella Warley, Fort Victoria, Ioannis P. Goulandris, Lizzie D., Macedonia, Malta, Manasquan Wreck (Amity), Mohawk (Revenue Cutter), New Era, Pentland Firth, Pinta, Pliny, Relief, Rjukan, Rusland, Sandy Hook, Scotland, Stolt Dagali, Sub Chaser 60, Thurmond, Western World, Yankee.

ISBN 1-883056-08-X, 2000 softcover with color covers, 6 x 9 vertical, 224 pages, 28 color photos, 56 black & white photos, 8 range drawings, 3 site plans. Over 400 loran numbers included.

To order this book and others like it, visit Gary Gentile's website at https://ggentile.com

Questions or Inquiries?

Just want to say Hello? Sign the .