Mohawk (4/4)

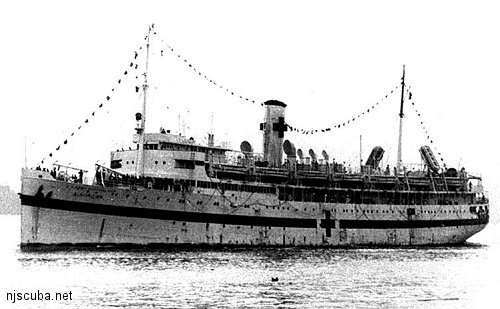

Just a few miles out of Manasquan Inlet (New Jersey), the remains of the Mohawk lie beneath 80 feet of water. The steel-hulled passenger ship, launched in October of 1925 by the Newport News Shipbuilding & Dry Dock Company, was 387' long, 54' in breadth, and listed at 5897 gross tons.

The Mohawk was the third in a string of disasters suffered by the Ward Line. First was the infamous Morro Castle fire at Asbury Park, then the Havana ran aground on a reef off Florida. The Mohawk was leased from the Clyde Line to take over the duties of the Morro Castle, but only a few months after the fire which claimed 124 lives, this ship also met with a tragic end. The Mohawk left New York on the afternoon of January 24, 1935.

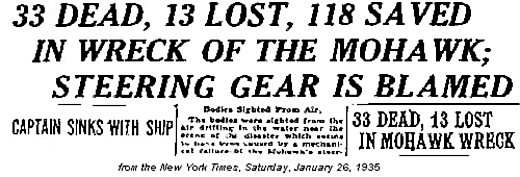

About 9:00 that evening, several miles south of Sea Girt Light and about six miles offshore, the steering gear went awry and the crew switched to a manual steering system instead. Shortly afterward, confusion between orders from the bridge and their execution in the steering engine room caused the Mohawk to execute a hard turn to port, at full speed, directly into the path of the Norwegian freighter Talisman. Although both ships tried to avoid the collision, it was too late. Talisman struck the Mohawk, and the latter began to take on water. Bitter cold, ice, and snow hampered the evacuation of the 160 passengers; all told 45 lives were lost, including Captain Joseph Wood and all but one of the ship's officers.

The Mohawk sank within an hour. Nearby ships came to the rescue, and Coast Guard boats and planes searched through the night and the next day, first for survivors, then for bodies. The wreck was later blasted to a maximum depth of 50' so as not to pose a navigational hazard in the heavily traveled shipping lane.

The Mohawk is one of the most dived wrecks in this area, although it resembles a ship less than an underwater junkyard. It's easy to get lost in the vast jumble of hull plates and twisted metal, so careful navigation is essential. Despite its popularity, this wreck still yields plenty of artifacts and lobster, and offers many interesting sights for the observant diver.

Original NJScuba website by Tracy Baker Wagner 1994-1996

A Survivor's Story

My parents, Sarah Jackson Smith and Samuel Smith, were among the lucky survivors [of the Mohawk.] My aunt Jennie Jackson wrote a kind of informal book of memoirs. I am enclosing my mother's account. My son - then 12 and now 44 - when he took diving lessons - he always talked of retrieving "Grandma's luggage." ( Yeah, sure! )

Sincerely yours,

Marilyn J Goldstein

The Brooklyn Bridge was one sheet of ice and as we crept along, inch by inch, wondered whether we would make it across the bridge, and if we did, would the Mohawk still be there waiting for us? Unfortunately, yes. As I was always seasick, I went down to our stateroom shortly after we boarded the ship and went to bed. In the short time that I was upstairs, I had remarked to Sam that all the lifeboats seemed to be buried in snow on the decks.

Four hours later, there was a terrible jolt followed by the complete standstill of our ship. Sam came running in and said we were rammed by a Norwegian freighter. He assured me that everything was under control. I put my coat over my pajamas and adjusted the life belt. We started through the passage to go to the deck. A seaman came running toward us. He had no life belt. I went back with him and gave him a second one which I had seen under my berth. On our second attempt to get to on deck, I met a woman whom I had spoken to briefly before I had left for my stateroom. She was returning for her jewels, which she had left in her stateroom. Unhappily, she was one of the forty-nine lost. Her body was later found floating, with jewels intact.

The lifeboats were dug out of the snow by us, as in those days they were not lifted by machinery. By this time, we were aware that a great gash had been made in our side and the ship was beginning to list. We finally raised one lifeboat, got it down the side of the ship and started to move away from the side of the ship. The lifeboat was filled to capacity with passengers and a few crew.

To our shock, we discovered that we were still tied to the Mohawk. A crew member started to shout for a knife to cut us away. Sam called to him to tear his coat open and pull out a gold penknife he had in his pocket, given to him by the Brooklyn Optometrical Society when he was president. As it was two degrees below zero, Sam's fingers were already frozen. The seaman found his knife, ran and cut us loose from the Mohawk.

We rowed away as quickly as possible, and had hardly gotten at a safe distance when we watched with horror - the Mohawk sinking with 49 people aboard, many of them young. Had we not gotten away when we did, we would have been sucked in with the Mohawk as she sank. We were picked up by the Algonquin several hours later and taken ashore, where we were met by a barrage of cameramen with endless questions.

We were happy to break away finally and go home. Betty and Jennie had met us at the pier with valises of warm clothes. We had sent a telegram earlier saying "saved Sarah Sam" the rest of the story is told by Jen her narrative of what happened in our home when the news was first broadcast.

Sam and I became active members of the Morro Castle safety at sea organization, founded by the survivors of the Morro Castle, which had burned off the coast of New Jersey with great loss of life. We later testified on numerous occasions before congressional committees in Washington about the terrible conditions which existed on board most of the American ships, the great fire hazards on many of the coastwise vessels, and the need for drastic changes which would make our ships safe for passengers and crew.

In 1936, the National Maritime Union called a strike in New York and all other United States ports to protest filthy and dangerous conditions on American ships and make demands for better wages, working conditions, hours, and modern safety equipment on all American vessels.

A citizens committee was formed, which I chaired. It was a rough strike, with freezing weather and much police brutality. We had a soup kitchen, obtained warm clothing for the strikers, found places for them to sleep, and ran meetings to raise money. This strike failed, but out of it came the 1937 strike which was a great victory for the seamen, resulting in increased wages, shorter hours, better working and living conditions, and new safety measures and equipment.

Sarah Jackson Smith's account

as told to Jennie Jackson, who put it in her memoirs

Of the Mohawk's three sisters, Cherokee was torpedoed and sunk June 15, 1942, by U-87 in a gale off Cape Cod ( 42-47N, 66-18W ) with great loss of life. Seminole and Algonquin served as hospital ships during World War II and were scrapped in 1952 and 1956

Credits:

- Side-scan sonar image courtesy of Capt. Steve Nagiewicz

- Document courtesy of Capt. Stan Zagleski / Miss Elaine B

- Survivor's Story courtesy of Dan Crowell

- Timetable courtesy of Maritime Timetable Images - www.timetableimages.com

Questions or Inquiries?

Just want to say Hello? Sign the .