RJ Walker / $25 Wreck (2/2)

Crew Explores N.J. Shipwreck That Time Nearly Forgot

ASBURY PARK, N.J. — Harry Roecker was the first to dive into the water when the RJ Walker Expedition, a collaboration of private and government divers, began its mission to complete the first archaeological survey of the long-lost government ship Robert J. Walker.

A moment earlier, Paul Hepler, captain of the Belmar-based boat Venture III, had positioned them over the wreck, in 85 feet of water, 10 1/2-miles off the coast of Atlantic City.

Roecker, his face pinched by a wetsuit hood, was given the task of tethering the down-line from the 46-foot aluminum crew boat to the highest point of the wreck. For the next six hours, divers shimmied up and down the rope like a conga line on the expedition's first day, last Thursday.

It was the first time any government employees had been back on the ship since the collision that sank it and took the lives of 20 crew members on the morning of June 21, 1860. It was the worst loss of life for a government ship in an agency that eventually would become the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

At 2 a.m. that day 154 years ago, while on its way from Hampton Roads, Va., to the Navy yards in Brooklyn, the Walker was chugging past the Absecon Inlet when it collided with the commercial schooner Fanny carrying 200 tons of coal 12 miles off the coast.

"Fanny knocked a hole or tore a hole or popped ribbons," said Jim Delgado, director of the NOAA's Maritime Heritage Program. "We're not exactly sure, but it left a hole in the side of Walker's bow just forward of the paddlewheel. The water started coming in with the force of a small waterfall."

In a mad dash, the crew tried to fill the tear with blankets and steam toward the direction of the Absecon Lighthouse. They never made it.

Those details of the crew members' final moments were recently confirmed by the expedition divers.

"We found remnants of blankets near the break where the collision happened," said diver Steve Nagiewizc of Brick.

Nagiewizc organized and coordinated the dive teams, along with Dan Lieb of Neptune, president of the New Jersey Historical Divers Association, and director of the Maritime Museum at Camp Evans in Wall.

"The purpose of this work is to create dive slates to act as tour guides for divers," Delgado said. "It's also for people who don't dive to understand what happened here. There are still echoes of the past in that rusted iron down there."

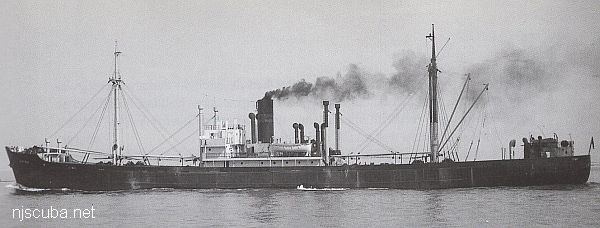

The Walker was a 132-foot sidewheel iron steamer built in 1844 for the Revenue Service, the original Coast Guard, to chase smugglers and collect customs. But it was too slow.

It was handed over to the U.S. Coast Survey, the oldest scientific agency in the country - now a department of NOAA called the National Geodetic Survey. It collected Gulf Stream data, using rope and lead to measure depth and mark channels for entry into ports.

The government, however, never earnestly probed the cause of the collision or looked for the ship.

"The Civil War was coming, so there was no real investigation," Delgado said. "The Coast Survey and the country moved on, particularly with the war, and the Walker was just largely forgotten."

A century later, a lobsterman accidentally found the wreck when his lobster pots became stuck in it. For $25, he sold the land ranges of the wreck to a local boat captain. Soon, more fishermen were using it, followed by divers.

However, until 2013, nobody knew the name of the wreck.

"We only knew it as the $25 wreck. That's what we called it," said Eddie Boyle, the retired captain of the dive boat Gypsy in Atlantic City.

In 1965, Boyle, now 86, salvaged the clue that would lead the government back to the Walker when he surfaced with a square porthole. Last year, he gave the porthole to friend and fellow diver Joyce Steinmetz.

"If it wasn't for fishermen sharing their unknown snags and diver's accounts, we wouldn't have had the clues of its whereabouts," said Steinmetz, a New Jersey native and a doctoral candidate in East Carolina University's nautical archaeology program.

Steinmetz, who was part of the expedition that concluded earlier this week, played a major role in identifying the Walker when she showed the artifact to Delgado.

NOAA then sent the vessel Thomas Jefferson, which was conducting a post-Superstorm Sandy coast survey, to officially identify the Walker. A funeral service was held, and the Walker was placed on the National Record of Historic Places.

This summer, a group from Richard Stockton College of Galloway and marine technology specialist Vincent Capone from Black Lazer Learning created the 3-dimensional sonar images the divers used to coordinate the dives.

Unlike the USS Monitor, where divers need a permit, or the USS Arizona, where diving is prohibited, the Walker site will be open to the public, but the recovery of artifacts will be prohibited unless coordinated with NOAA research.

"We want to encourage people to dive. It's one more jewel in the crown of amazing New Jersey wreck dives," Delgado said.

Large-scale drawing of the wreck site

Identification of the Wreck of the U.S.C.S.S. Robert J. Walker off Atlantic City, New Jersey

Questions or Inquiries?

Just want to say Hello? Sign the .