City of Athens (2/2)

Chapter 13: City of Athens

reprinted from Shipwrecks of New Jersey: South by Gary Gentile

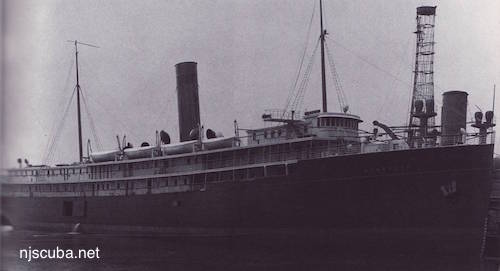

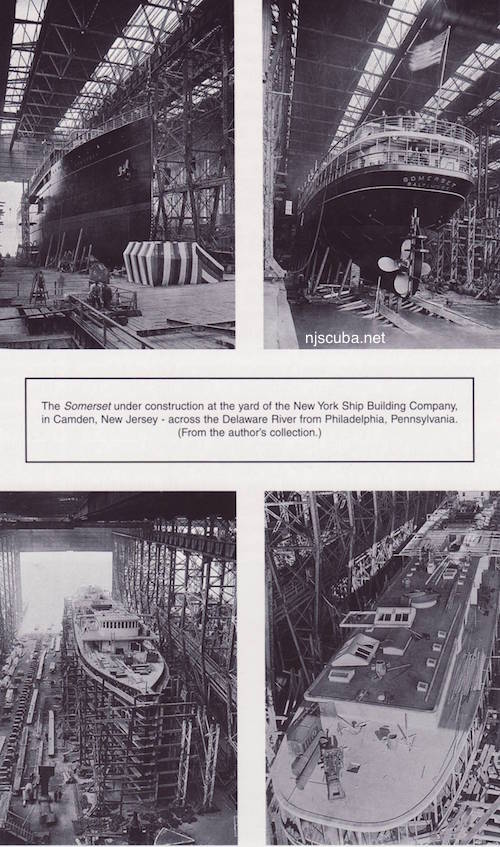

| Built: | 1911 |

| Previous names: | Somerset |

| Type of vessel: | Passenger-freighter |

| Gross tonnage: | 3,648 |

| Dimensions: | 309' x 46' x 19' |

| Power: | Coal-fired steam |

| Builder: | New York Ship Building Company, Camden NJ |

| Owner: | Ocean Steamship Company, Savannah, Georgia |

| Port of registry: | New York, NY |

| Sunk: | May 1, 1918 |

| Cause of sinking: | Collision with French cruiser La Gloire |

| Depth: | 105 feet |

The loss of the City of Athens was one of the most lamentable maritime tragedies to occur off the New Jersey coast since the tum of the twentieth century. Under the name Somerset, she was in the coasting trade between New York and Savannah, Georgia, carrying passengers and freight. On September 14, 1917, the company changed the vessel's nomenclature to City of Athens. Service went uninterrupted, and passengers continued to cross the Mason-Dixon line with identical regularity.

The passenger-freighter departed New York on April 30, 1918, and proceeded southward along the New Jersey coast. On board were one hundred thirty-five passengers and crew, and a cargo of general merchandise. Most of the passengers were U.S. Marines and French sailors. By midnight, all the passengers and many of the crew were asleep.

Fog hung in patches over the coastal shipping lanes. Visibility was made worse by the addition of rain. Captain A.C. Forward, master of the City of Athens, ordered a reduction in speed. The ship's steam whistle sounded plaintively at regular intervals as a way of announcing her unseen presence to other vessels. Because of the war, and the possibility that a German U-boat might be lurking in the neighborhood, the ship's portholes and deck lights were darkened. Only the navigational sidelights were burning. The rain and fog ended suddenly at the latitude of Atlantic City, but shortly thereafter, the ship entered another fog bank that was thick and clinging. Extra lookouts were posted.

Captain Forward later described ensuing events: "About 1:10 a.m. fog signals of an approaching vessel were heard, but her exact location could not be ascertained. Suddenly a steamer loomed up out of the fog almost directly dead ahead and very close. The first known of the vessel's close proximity being when we saw her lights. It was then too late to avoid a collision and the steamer ... struck the ... City of Athens on the starboard bow about at the anchor winch penetrating into the City of Athens to the navigating bridge."

The ship that struck the City of Athens such a devastating blow was the French cruiser La Gloire.

On reporter noted, "The shock, which appeared to lift the steamer out of the water, combined with the grinding of steel plates ripped out of the side of the boat and the splintering and snapping of woodwork, was sufficient to indicate to all, who were roughly awakened from sleep, that the ship would not last more than a few minutes. Most of the passengers rushed up on deck with life-preservers slipped over their night clothes and some with overcoats and slippers on. The women were hastily put into lifeboats and life-rafts, as fast as they could be got off. French sailors and American marines, who were among the passengers, togcthcr with three young sailors of the United States Naval Reserve, who were being trained for commissions, joined in saving passengers."

Passenger John Wilson, a young marine, gave a graphic account of the efforts to abandon ship. "I was fast asleep and dreaming when my dream was broken by a terrific crash. I jumped out of bed and looked out of the window. I heard a bugle from the French boat and I shook my partner in the bunk, above a man by the name of Graham - and told him he had better hurry. Somehow I could not make him understand. He just rubbed his eyes, yawned, and wanted to turn over and go to sleep again. I learned later that he was drowned."

"On rushing out on deck I found the boat listing far to port and a group of men, with a woman among them, struggling like mad with a lifeboat. A crowd of them got in with the woman, but just as I arrived a rope or something broke, the lifeboat turned clear over, and every one in it tumbled into the water. Feeling the steamer sinking ( didn't think it was worth while bothering about lifeboats, so I slid down a pole to the deck below, and just as I was about to leap off the rail a big wave piled over thc side and swept me overboard. When I rose to the surface I round myself looking right into thc eye of a searchlight."

"That gave me hope and I started to swim toward the ship. On my way I met a French sailor who was one of the passengers on our boat, and who was holding onto a box. I asked him if he would mind if I took hold of the box too. He could not understand what I said, but nodded his head, and I promptly grabbed hold. Then with one hand on the box and the other to his mouth, the French sailor would raise himself out of the water and shout 'Sauve! Sauve!' toward the warship. Finally the French sailors heard him, and one of their boats came out and picked us up."

Marine Ned Rogoff had a similar experience. After being awakened by the crash, "I put on my trousers, my coat and my shoes. I got into the saloon deck and found that the boat was listing, with the stern rising fast. At the upper end of the saloon a woman came from one of the staterooms, and as soon as she saw me she rushed down and seized me around the neck, begging me to save her. The boat continued to list downward and I felt my feet sliding from under me."

"With the woman still around my neck I tried to grab for a table in the saloon, and finally succeeded in seizing hold of the foot of the piano, with the woman, who had fallen to the floor, holding on to my foot. The piano began to slide, too, and down we went, all three of us - the woman, myself, and the piano. We banged against something, and - I don't know what happened, but the next moment I was out on deck, rushing toward a lifeboat, which some men were just about to put off. I was on the point of getting into it when one of the ropes gave way and everybody in it was hurled into the water."

Rogoff then climbed up to the highest point of the deck above the water and found a life raft lashed to its place. He grabbed onto the raft, and after a minute or two he heard what he thought was a boiler explosion, after which he found himself still clinging to the raft, but in the water. A man and a women were holding on to the other side of the raft, "the woman pleading with her husband to save himself and let her go."

"These two, I learned later, had two children on board, one of whom was drowned. Apparently the explosion or whatever it was, had separated the raft from the deck. Anyway, we floated around and pretty soon I saw emerge from the water a few feet away, the head of a steward. He shouted for an oar, and I shoved one toward him. Then came a Negro. He floated by with his face all bleeding. He blubbered something or other to me and floated on."

"We saw several lifeboats pass us, and I shouted, but none of them would stop. I guess they thought we were well enough provided for with the raft. It was not until I yelled to one boat that we had a woman with us that it stopped, and we would not let it pass until we all got aboard."

Marine Frederick King had an experience that wreck-divers will find of particular interest. "I climbed to the highest part of the ship, and then there was nothing to do but let go and slide down the whole length of the deck and land in the water to find right within reach a floating door and a nice, soft cushion on top of it. I climbed on top of the cushion and sat there, feeling quite comfortable and as secure as the circumstances would permit, and just waited to see what would happen next.

"After floating around for fifteen minutes there emerged out of the sea what looked to me very like half of the upper deck, with a cupola-shaped pilot house and everything right side up. It offered an even more inviting perch than I had, so I swam out to it and got on top of the cupola. Pretty soon a young naval cadet swam up and got aboard with me and started to give me a lot of pointers as to how to keep from freezing by lifting my feet out of the water and moving my arms around. I followed his directions and we sat there, watching a lot of things floating by us in the fog. Now it would be a man, sometimes a woman, holding on to a box, and almost the last thing I saw were four negroes sitting on an overturned lifeboat and praying at the top of their voices."

King and his unnamed companion were discovered by the beam of the French cruiser's searchlight, and taken off their giant raft by one of the warship's boats. How far the pilot house drifted before it sank - taking with it to the bottom the navigational equipment - is unknown. In the 1970s, Tony Vraim found the brass helm stand about one hundred feet off the port side of the wreck, adjacent to where the pilot house would have been located. Jim White and the author assisted in its recovery.

Marine Harold Weeks was washed overboard. He found a box to hold on to, then a door, and then saw a raft with a man on it. "I asked him if I could get on, but he shook his head and said he thought it would go down with two of us. But I got on and hung on until a boat came along and picked us up."

Most of the people aboard the lifeboat that overturned were drowned. Only two other lifeboats were launched successfully before the City of Athens slipped beneath the waves - a bare seven minutes after the collision. La Gloire hove to and dropped anchor nearby. Although her bow was seriously crumpled, she was in no immediate danger of sinking. She launched and manned lifeboats to search for survivors. Powerful searchlights played across the water, picking out people clinging to lengths of timber and other kinds of flotsam. Marine Harold Cooper clung to a bit of partition for fully three hours before a lifeboat picked him up. By that time his fingers were so numb from cold that he was close to letting go. Rescue operations were hampered by the fog, yet the La Gloire's boats managed to pluck sixty-seven people from the water.

The loss of life was appalling: sixty-eight men, women, and children. F.J. Doherty, the wireless operator, died at his post while tapping a continuous SOS. Of sixty-six crew members, thirty-four died. Of twenty-five non-military passengers, thirteen died. Of twenty-four marines on their way to the training camp at Port Royal, seven died. Of twenty French sailors, fourteen died. It is ironic that these French sailors died as a result of a collision with a French warship - which begs two questions that were never answered: why was a French warship patrolling American waters, and why were French sailors taking passage on an American coasting vessel?

At the time of her loss, insurance on the hull and cargo of the City of Athens was underwritten primarily by the Insurance Company of North America. INA paid more than half a million dollars to settle the claims. However, the underwriters determined that the cruiser was at least partially responsible for the collision. They tried to subrogate their claims against France. Thc French government refused to recognize any responsibility. When INA sought to have the government intercede in its behalf, the government demurred. The case dragged on until long after the war was ended.

INA's counsel advised, "We consider that the City of Athens was clearly at fault, but we believe that our courts would hold that the cruiser was also in fault for proceeding at too great a speed in the fog. A plea would undoubtedly be made that a cruiser's speed cannot be limited by International Law, but we think that our courts would hold otherwise."

Counsel was indeed perceptive, for when INA filed suit on its own - after receiving support from both American and British underwriters - the French Ministry of Marine responded by stipulating that a warship needs to proceed at a higher speed not only because she was therefore more maneuverable, but because she was operating in U-boat infested waters and was on a "special mission." In other words, it was dangerous for a merchant ship to proceed through fog at twelve knots, contrary to Article 16 of the International Rules, but not so for a warship in the performance of her duties in time of war.

The purpose of the so-called "special mission" was never admitted.

Furthennore, at the time of the collision, U-boats had yet to make their appearance in American waters. The first U-boat did not arrive off the coast until the end of the month. ( For details, see the Special Report at the back of the book. )

The French Minister of Marine rebuked the claim, stating that the collision was "attributed to the thick fog and constitutes a case of 'forces majeure' ( equivalent to the English idiom "act of God" ) which does not involve the responsibility of either of the two ships. I have therefore decided ... that the damage would be borne by those who suffered them." For a country whose fat was pulled out of the German fire by the lives of American soldiers and American war materiel, this was a hard stance to take.

To further complicate matters, "prior to May 1, 1918, the Director General of Railroads, pursuant to statutes of the United States and Proclamations of the President of the United States, took possession and assumed control of Ocean Steamship Company of Savannah, its steamers, wharves and equipment, and among the steamers possession and control of which was so taken and assumed was the City of Athens."

This meant that, whereas the U.S. government was in nominal control of the company and its ships, and whereas the government conveniently determined that the casualty was a result of war, and whereas the insurance policy was written against all perils "but specifically excepting from the coverage extended thereby any and all loss or damage arising from the direct or remote consequences of any hostilities and also from loss or damage resulting from measures or operations incident to war," INA should never have paid the claim in the first place. Such indemnity should therefore have been paid by the U.S. government, which by legal technicality was responsible for operating the City of Athens at the time of her loss.

INA and associated re-insuring agents subsequently sought reimbursement from the U.S. government. The one year statute of limitations was waived because it did not apply "in assertion of the sovereign rights of the United States." In 1932, counsel for the underwriters argued that unless "it should develop that the cruiser La Gloire was, at the time of the collision, en route to port merely for the purpose of coaling or drydocking or some such non-warlike mission," the war risk exclusion applied.

The counterpoint made was that monies voluntarily paid could not be legally recalled, even if a mistake was made in payment. INA insisted that any monetary outlays were made in good faith: not as a final settlement, but in the nature of an advance on the ultimate legal decision.

The case is still open.

The Ocean Steamship Company lost at least as much as INA because the City of Athens was greatly under-insured. Her estimated valuation was $600,000, yet she carried only $36,000 worth of hull insurance. The rest of the insurance premium was paid to cover her cargo, which is still being recovered by divers.

The wreck sits upright in an advanced state of collapse. The hull is contiguous, with the stem and stem clearly identifiable. The sides have fallen away haphazardly, and the decks, which fell straight downward, are rusted through to the extent that the cargo holds are exposed. The engine and two boilers lie fairly close to amidships.

Due to the large number of rifle bullets found in the remains of the forward cargo hold, the City of Athens is fondly known as the Ammo Wreck. The broken ammunition cases lie mostly on the port side, which is a prime area for digging up cartridges and other artifacts. Closer to the centerline there are great quantities of small bottles of nostrums and patent medicines: Dr. King's New Discovery For Coughs And Colds, the always smelly Sloan's Liniment, and Fletcher's Castoria; to name a few. Many bottles have retained their corks and original contents. Milk glass jars such as Champlin's Liquid Pearl lie among smooth, round brown glass bottles with rubber stoppers.

Just forward of the engine, where rolls of linoleum lie under rusted deck beams, is the place to dig for assorted glassware, brass locks, brass flashlights, and Vodrey china. One group of divers spent several summers retrieving six of the eight bronze searchlights carried as cargo.

Gauges are found occasionally around the engine and the boilers. Magnolia anti-friction bars are found in the after part of the wreck. Lobsters appear to be everywhere. This is because thc hull has collapsed in such a way as to make metal caves and overhangs, which these crustaceans utilize as hiding places. Fish of all kinds abound.

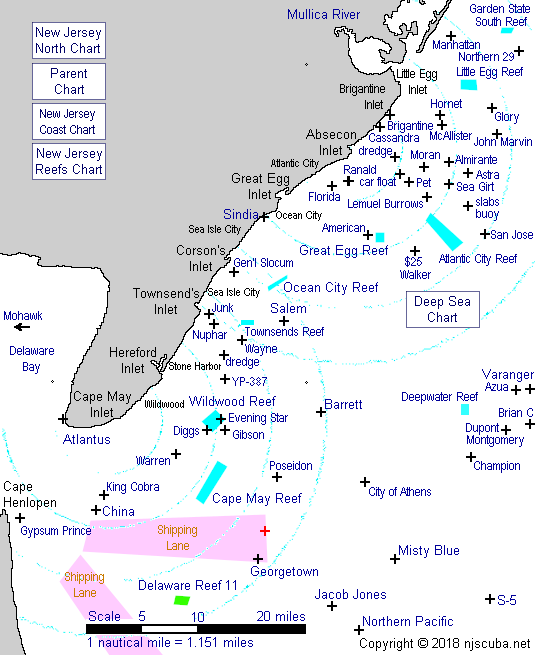

Because of its distance from shore, the City of Athens is also known as the 26 Mile Wreck.

GARY GENTILE'S POPULAR DIVE GUIDE SERIES

Shipwrecks of New Jersey: South

As suggested by the title and series name, this volume covers the most well-known wrecks sunk off the south geographical coast of New Jersey: from Egg Harbor Inlet ( just north of Atlantic City ) to the Delaware border ( which bisects the approaches to the Delaware Bay. )

For each of the wrecks covered, a statistical sidebar provides basic information such as the dates of construction and loss, previous names ( if any ), tonnage and dimensions, builder and owner ( at time of loss ), port of registry, type of vessel and how propelled, cause of sinking, location ( Loran coordinates if known ), and depth. In most cases, an historical photograph or illustration of the ship leads the text. Throughout the book is scattered a selection of color underwater photographs, some of the wrecks, more often of typical marine life found in the area.

Each volume is full of fascinating narratives of triumph and tragedy, of heroism and disgrace, of human nature at its best and its basest. These books are not about wood and steel, but about flesh and blood, for every shipwreck saga is a human story. Ships may founder, run aground, burn, collide with other vessels, or be torpedoed by a German U-boat. In every case, however, what is emphatically important is what happened to the people who became victims of casualty: how they survived, how they died.

Wrecks covered in Shipwrecks of New Jersey: South are: Admiral Dupont, Almirante, American, Astra, Atlantus, Azua, Brian C, Carolina, Cassandra, Cayru, Champion, Charles Morand, City of Athens, Dorothy B. Barrett, Edward H. Cole, Eugene F. Moran, Florida, George R. Skolfield, Gulf Stream, Harry Conrad, Huntsville, Isabel B. Wiley, Jacob M. Haskell, Jewess, J.W. Hawkins, Kennebec, Lake Frampton, Lemuel Burrows, Maryland (General Slocum), Montgomery, Nuphar, Oklahoma, Patrice McAllister, Pocahontas, Powhattan, Ranald, Right Arm, Rio Tercero, San Jose, Sindia, Texel, Varanger, William B.Diggs, Winneconne, YP-387, and a Special Report on June 2, 1918: Black Sunday and the U-151.

To order this book and others like it, visit Gary Gentile's website at http://ggentile.com

Questions or Inquiries?

Just want to say Hello? Sign the .