Lost At Sea (2/9)

Lost At Sea

By Douglas A. Campbell

Philadelphia Inquirer, 1999

Seaman's Wager

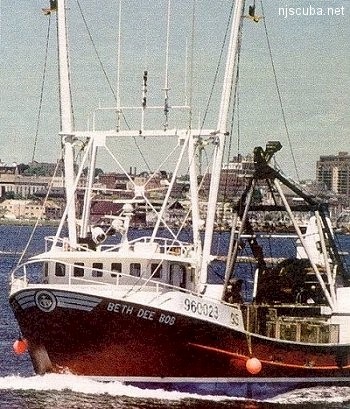

POINT PLEASANT, N.J. - Michael Hager had already lost his chance for a big payday when, in the long, cold shadows of a clear dawn on Jan. 5, 1999, he arrived at the clam dock. It was 7:30, about the time the 84-foot clam dredger Beth Dee Bob gunned its diesel engine like a bus leaving a curb, dug its propeller into the gray-green water, and pointed toward Manasquan Inlet and the fickle Atlantic Ocean. Instead of including Hager, the crew on that red and white boat was made up of four other men.

Hager, 31, a veteran of 13 years at sea, knew the dangers aboard a clam boat in treacherous winter seas. Yet he would have traded places with any of those four men that Tuesday morning, for they were to return to this dock in 36 hours, earning pocketfuls of money. Edward McLaughlin, the burly, easygoing captain of the Beth Dee Bob, had offered Hager work on three trips. Hager made the first trip. But he decided to spend New Year's Eve with his son, Mikey, 5, and left McLaughlin scrambling to complete his Dec. 30 crew. Hager was not invited back.

Now, Hager faced the consequence: Another cold day in the bilges of the Adriatic, making repairs to the aging clam dredger tied to pilings along Wills Hole Thoroughfare. Hager's work in the Adriatic would be $350 for the week. His wages aboard the Beth Dee Bob would have been more than $500 for 1 1/2 days' work. Mike Hager turned the key to unlock the Adriatic for the welders and to start his own labors, even as the Beth Dee Bob steamed east.

What none could have imagined as their routines got underway that morning were the events that were about to unfold. For the next 13 days would be among the deadliest ever at the clam docks along the New Jersey coast, where most clamming vessels in the North Atlantic fleet bring their catch one time or another, year-round. In stunning succession, four clam boats would sink and 10 men would die, five of them never to be found.

The four vessels were part of a fleet of 48 that set out one year ago this week with their 1999 quotas to take 4 million bushels of quahogs and 2.565 million bushels of surf clams, worth a total of about $44 million at the dock. The four lost boats represented a cross-section of that little flotilla: the Beth Dee Bob, one other state-of-the-art stern ramp dredger, a 20-year-old steel vessel with no modern clamming equipment, and a wooden boat of similar vintage that had once survived a catastrophic fire.

The men lost with these floating factories were also a fair example of their breed, ranging from a 51-year-old sea captain, who three weeks earlier had fallen wildly in love, to a 21-year-old college student out to make some money during winter break. Among the survivors were those who vowed never to set foot aboard another boat, and others who quickly returned to the waters where their shipmates found graves. There were dozens of grieving relatives and hundreds of friends at five funerals and as many memorial services. And there were questions, among them whether commercial fishing, the most dangerous industry in America, could be made a bit less deadly.

For three sailors who survived one of the sinkings, there was no doubt why their boat sank. Only the timing of it, in the midst of those 13 days, seemed peculiar. But after the coffins were closed and the inquiries completed, uncertainties remained concerning why the other three vessels went down. The answers lie in the men, the machines, the industry, and nature - the as yet unchanged world of commercial clamming.

No one on the docks that January would have called Ed McLaughlin, 36, anything less than a prudent skipper. Prudent and loyal. When his boat owner, PMD Enterprises, called with a last-minute assignment, McLaughlin canceled his New Year's Eve plans with his wife, Lisa, called off the babysitter for their 2-year-old son, Liam, and went to sea Dec. 30 to catch one last load of 1998 quahogs. Lisa got a consolation dinner on Saturday night, Jan. 2, when Ed returned. They ate at the candlelight and linen Ebbitt Room in Cape May - steak for her, fish for the sea captain - and then strolled the empty winter streets of the town where they met in the summer of 1987, talking of a new home, a planned Florida trip.

Three days later, Lisa got a phone call about 9 a.m. Ed was calling from his boat. He was already 15 miles out, crossing the "Mud Hole, " a notorious stretch of the Atlantic where storm-blown seas pile up against a seabed cliff, creating waves twice the normal size. On this morning, the Mud Hole's treachery was in check. Ed and Lisa talked about moving into a townhouse. Sitting in the wheelhouse with a newspaper in his lap, Ed gave his wife some real estate phone numbers. Then they said their good-byes, and McLaughlin continued to steam toward his destination 70 miles to the northeast, not far from the Long Island shoreline.

Down below, sleeping in a bunk room under the wheelhouse, lay Jay Bjornestad, the first mate, 38 and string-bean skinny, and Roman Tkaczyk, 48, a deckhand from Gdansk, Poland. The other deckhand was Grady Gene Coltrain, 39, who was making his first trip on the Beth Dee Bob. Coltrain, who stood 6-foot-4, was a lanky, rugged man who liked to write love poems. He spent his free time reading horror novels at the galley table. At 3:30 a.m., he had phoned his common-law wife, Anna Puglisi, a night nurse at a South Jersey hospital. "Have a safe trip, " she told him. She would rather he work as a carpenter, his other trade.

Under the galley table on the Beth Dee Bob were four survival suits, red neoprene coveralls that could save a man's life if he had to jump into the freezing Atlantic. On the wheelhouse roof were the life raft and emergency position indicating radio beacon - or EPIRB. Up in the wheelhouse, McLaughlin, a confident, likable man with the 18-inch neck of a power-lifter and a scholar's fondness for reading, watched the radar screen. The autopilot steered the boat, and the helm remained motionless and untouched.

Above the helm was a snapshot of Liam on a hobby horse, with Lisa. From time to time, McLaughlin glanced up at two television monitors that showed images from the engine room under the afterdeck. He could watch a video on the VCR. In boring times like these, he often practiced tying knots in a drinking straw with one hand. McLaughlin, a commercial fisherman for 17 years, had been captain of the Beth Dee Bob for four of its nine years. The boat was 84 feet and 3 inches long and 26 feet wide. Its afterdeck was about 18 inches above the water, and the windows of its low wheelhouse were just even with the tip of the high bow.

Behind the wheelhouse was the clam hold, a huge steel box welded below the deck and covered, when the boat was steaming, with huge steel lids called hatch covers. Outriggers - 30-foot-long poles - were lowered on either side from a superstructure of welded steel. When the boat reached the clam beds, 2-foot-long objects shaped like space shuttles and called divers or birds would be lowered from the outriggers on cables, 20 feet below the surface, to keep the boat from rolling. A steel ramp towering above the deck as high as a two-story roof slanted up from the vessel's stern toward its bow, and a huge steel cage - the dredge - rode atop it. Mike Hager, who was dazzled by the boat's high-tech equipment, had found one feature of the Beth Dee Bob peculiar. The bunks were all below the waterline, under the low wheelhouse.

It was McLaughlin's practice to rouse Bjornestad from his bunk when he reached the fishing grounds and to nap during the first half of the 22-hour-long dredge while the first mate operated the boat. Bjornestad, who had joined McLaughlin when the Beth Dee Bob was working out of Shinnecock, Long Island, in 1996, now lived a half-mile from his captain in Absecon and carpooled with him to the dock.

It was 2 p.m. when the Beth Dee Bob, in 200 feet of water, arrived at the clam beds 20 miles off Long Island. Coltrain and Tkaczyk were on the afterdeck, preparing the machinery. The air was slightly warmer than the 28-degrees high predicted onshore, and the heavy work quickly built a sweat. Bjornestad worked the controls, and the dredge, released from its ramp, slid with a machine-gun rattle into the water. The dredge, a 20-foot-long scoop made of welded steel rods and steel bars, pulled with it the steel cable from the boat's massive winch, along with a towing rope as thick as a strong man's wrist.

The dredge also drew down the end of a black rubber hose 10 inches in diameter and as long as the towing rope. A pump inside the Beth Dee Bob sucked up seawater and forced it through this hose to nozzles across the front of the dredge, churning the ocean floor, roiling clams from their hiding places in the mud or sand.

Bjornestad towed for 10 or 12 minutes at a little over two knots - just above two miles an hour - then started the winch. The dredge rose on the ramp, an elevator in an open-air shaft. Water cascaded from the dredge, which emptied its load into a hopper below the ramp. Seagulls began hovering over the boat's wake like shoppers waiting for the doors to open on sale day. As mechanized equipment shook the small debris and fish from the catch and shot them overboard, the screeching gulls dived.

The sorted quahogs, black and the size of hockey pucks, rode forward on conveyor belts. Coltrain and Tkaczyk, the taste of salt air on their lips, the sweet smell of raw seafood in their noses, diverted the quahogs down stainless steel chute. The shells clattered like falling rocks into the holds, loaded with steel cages three by four feet wide and five feet high. No one could talk above the racket. As each dredge surfaced, more cages were filled with 32 bushels of quahogs each, and the Beth Dee Bob grew heavier.

At midnight, the boat's deck lamps lit the black horizon. Coltrain and Tkaczyk were halfway through their long hours on deck, and McLaughlin was about to relieve Bjornestad at the helm. By 3:45 a.m. Wednesday, McLaughlin had used one of his radios to listen to a weather forecast. He didn't like what he heard. He raised the Danielle Maria, another PMD clam boat, and spoke to the captain, Joel Stevenson.

"Man, did you hear that weather?" McLaughlin asked. "No, don't tell me they got weather, " Stevenson replied. "I'm looking for a nice day today." "No, they got bad weather up tonight. I wouldn't go where you're headed." Stevenson turned to the weather channel on his radio and then called back. "Man, you're not kidding. They got that wind coming up tonight." McLaughlin persuaded Stevenson to work 38 miles from the dock rather than pushing for a spot near Long Island. At this point, McLaughlin was catching steadily and had only 19 of 67 cages left to fill before he turned for home. The last dredge came up at 11 a.m., just when the wind started blowing from the southwest. Bjornestad took over the helm, and it was McLaughlin's time to rest.

Heading back to Point Pleasant, the Beth Dee Bob, which had been approved by a naval architect to carry 70 full cages, had 48 cages in its hold and 11 more resting on the deck. Each full cage weighed 3,400 pounds. The top third of eight more full cages poked up from the forward hold, with the hatch cover drawn like bedclothes to hold them in place, a practice the architect had forbidden because of the risk of water filling the hold. With the boat driving directly into the increasing wind and waves, no one worried that water would get in where the cages protruded from the forward clam hold. Clammers knew that seas breaking over the bow would part and thus would never reach that opening.

As the afternoon of Jan. 6 progressed, Bjornestad kept in radio contact with the Danielle Maria. "Man, I'm taking a lot of water over the bow, " he told Stevenson. In their berths below the water line, McLaughlin, Coltrain, and Tkaczyk were getting a rough ride. There wasn't a man aboard who had not been in similar seas, but that didn't make them any more comfortable as they headed home.

Coltrain would be going to Cherry Hill, where he lived with Puglisi and their two children - Sarah, 12, and Justin, 8. He was divorced from his first wife, and his 14-year-old son, Grady Gene Jr., lived in Virginia. February would be a big month in his life. He would turn 40 on the 16th, and he and Puglisi would get married after 13 years together.

Tkaczyk had a wife, Aolanta, and a son, Damian, 14, in Poland. He worked the fishing boats on the Atlantic coast, stayed in Philadelphia when ashore, and sent money home to his family. He was known for quitting boats without explanation, a quirk that was tolerated because he was capable.

Bjornestad and his wife, Charlene, lived with their daughter, Theresa, in Absecon, but their real home was on Long Island. Bjornestad had fished for 18 years, sometimes as captain of a fishing boat in Florida. He joined the Beth Dee Bob as a deckhand and in three years worked up to first mate. Bjornestad's longevity was uncommon on McLaughlin's boat, where 47 deckhands - an unusually high number - had worked since 1994. The captain used to tell PMD's boat manager, Ernest Riccio: "I'm just looking for a warm body to go."

The birth of Liam had transformed McLaughlin from party animal to proper parent. He wanted nothing more than to be home with his son. When the two were together, playing with cars on the floor or with the computer, Lisa sometimes seemed invisible. She loved her husband for that.

By 4 p.m., after 32 hours at sea, McLaughlin could sleep no longer and was up in the wheelhouse with Bjornestad. The evening closed in from the east, and by 5:30, with snow blowing in flurries, the Beth Dee Bob was steaming toward the fleeting tinges of day, approaching the Mud Hole.

On the Danielle Maria, first mate Larry Kirk was steaming in, as well, having relieved Stevenson. He had quit clamming at 3:30 p.m. with only half a load. In what Kirk estimated was one of the nastiest seas he had sailed in 30 years, he had been unable to keep the dredge on the ramp. The wind reached 40 knots, blowing foam in long streaks off the 10-foot waves. Kirk radioed the Beth Dee Bob and talked with McLaughlin. "Ed, is it getting any better in there?" he asked. "Yeah. Once you get inside eighteen miles, it's good, " McLaughlin replied. "Oh, great, 'cause I'm getting my a- kicked out here, " Kirk said. He was 90 minutes behind the Beth Dee Bob.

It was 10 minutes later when Kirk next heard McLaughlin's voice on the radio. " Danielle Maria, are you there?" He sounded distressed. "Yes, Ed, I'm there, " Kirk answered. "What's going on?" "I'm taking on water, big time!"