U-869 (4/5)

History Submerged

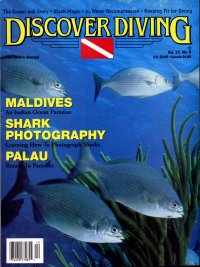

reprinted from Discover Diving magazine, December 1995

by Professor Henry Keatts

On September 2, 1991, Captains Bill Nagle and John Chatterton with the crew of the dive charter boat SEEKER discovered an unidentified U-boat off the coast of New Jersey. The find was based on Loran numbers for an unidentified shipwreck that had been provided by a commercial fisherman during 1990. Schedule conflicts and inclement weather kept Nagle and Chatterton from visiting the site approximately 60 miles off Barnegat Inlet, but in September 1991 an open weekend and a favorable weather prediction permitted such an offshore trip. Nagle invited several experienced wreck divers to join the search for the wreck, reportedly in over 200 feet of water.

When the mystery wreck was located at 39°33'N, 73°02'W, in about 230 feet of water, it was identified as a submarine, but not which one, nor even whether it was American or German. No artifacts were recovered on the first two trips that would identify its nationality. A third trip on September 29, 1991, was more productive.

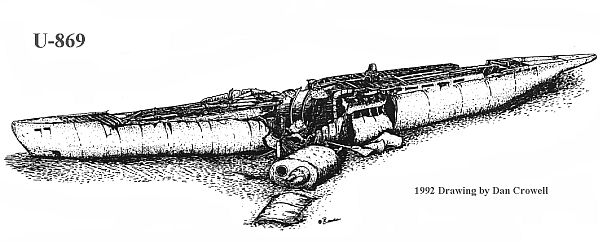

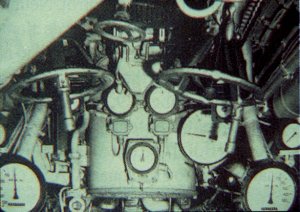

The conning tower was separated from the hull and laying in the sand. The port side of the control room was almost completely demolished from bulkhead to bulkhead, nearly separating the submarine into two pieces. Captain Chatterton dropped into the damaged area and passed through the forward control room hatch into the radio room and Captain's quarters. Continuing forward, he passed through another hatch into the galley and found three small plates and two soup bowls. After returning to the dive boat, Chatterton inspected his artifacts. He was dismayed to find that the small dishes had no markings. However, the two soup bowls were marked with an eagle and swastika, a large M representing the Kriegsmarine ( Germany's World War II navy ) dated 1942.

Other divers recovered pieces of life rafts with German markings. Steve Gatto and Tom Packer, both of Atco, New Jersey, used their dive to dig in the pile of debris where the control room once was. Gatto recovered a bronze "UZO, " a torpedo aiming device inscribed with an eagle and swastika and the large M. Those artifacts identified the wreck as a German U-boat and the hull configuration indicated it to be a Type IX, but the question remained: Which U-boat? Neither U.S. nor German naval records show a U-boat casualty within I 00 miles of the site. Skeletal remains were viewed on subsequent dives. Captain Chatterton recovered a knife with a wooden handle, and on the handle was the hand-inscribed name "Horenburg." That knife proved to be the key to solving the mystery of the U-boat's identity.

In December 1993, Captain Chatterton sent an inquiry, with information, sketches, and photographs of the U-boat to the Naval Historical Branch of the Ministry of Defense, London, England. In turn, the Naval Historical Branch forwarded the inquiry and material to Berlin, Germany for assessment by Dr. Axel Niestle, an authority on U-boats.

In July 1995, after reading my book, Dive into History: U-boats, co-authored with George Farr, Dr. Niestle sent me a copy of the report he had produced for the Naval Historical Branch for discussion and distribution. He concluded that the mystery U-boat referred to as " U-Who" by sport divers is U-869.

The Mystery of U-869

U-869, a Type IXc U-boat under the command of Kapitanleutnant Helmut Neuerburg, left Kiel, Germany on November 23, 1944 for snorkel training at Horten, Norway. The snorkel was a twin air-intake and exhaust tube that permitted a submerged submarine to operate its diesel engines instead of the much weaker electrical engines.

On December 3, it left Horten for Kristiansand-South to take on fuel and provisions. Nine days later the U-boat left for her first war patrol. Neuerburg was ordered to move northwards along the Norwegian coast before breaking into North Atlantic waters via the Iceland-Faeroe gap.

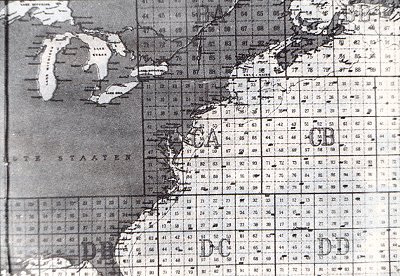

On December 29, Commander-in-Chief, U-boats ( Befehlshaber der Unterseeboote [BdU] ) ordered U-869 by radio signal to head to grid square CA 53 ( 40' N, 72' W ) off the U.S. coast. All U-boats carried such grid-covered charts ( duplicates of those at U-boat Headquarters ). The grid system allowed BdU to deploy U-boats without fear of enemy interception of his orders. In turn, the U-boats could keep headquarters informed of their locations without fear of providing the information to the enemy.

U-869, however, did not respond to the December 29 BdU order. The following day the U-boat was ordered to report her position, but there was no response. On January I and January 6, 1945, BdU repeated the order, but without results. The BdU's war diary ( KTB ) for December 30, and January 3, reflects anxiety over the U-boat's probable loss.

On January 6, U-869 finally reported in, but its position was inadequately fixed. From the position reported, BdU assumed the U-boat had used the Denmark Strait instead of the Iceland Passage to enter the Atlantic and was concerned about the impact of the longer course on U-869's fuel supply. The U-boat was ordered to continue southward and report the state of fuel and position the following night and reissued the order concerning its operational area ( CA-53 ).

When U-869 did not report in, BdU radioed the U-boat to change its patrol area to the west of Gibraltar ( CG 92-95 ), excluding the Gibraltar Strait; that area was heavily patrolled by Allied warships. U-869 was ordered to remain submerged and use its snorkel on the approach route after entering square CG; Allied aircraft patrolled the area and a surfaced U-boat would be an easy target. Forty-seven percent of U-boat sinkings during the war were attributed to Allied aircraft, a far cry from the relatively ineffectual role of the airplane in World War I anti-submarine action. Dr. Niestle stated, "The change of the operational area for the U-boat was probably based on the assumption that the longer outward route had reduced its fuel stocks to the extent that distant operations off the U.S. coast were no longer possible."

On January 8, 1945, U-869 reported its fuel supply but did not acknowledge the change in operational area. The radio report was repeated the following day. Dr. Niestle states, "Although the last two messages were intercepted by Allied radio stations, apparently they were not received by BdU, as he again ordered U-869 on January 9 to report its fuel state during the next night." This time U-869 reacted promptly, reporting its fuel supply on January 10, but again did not acknowledge the change in operational area. The intercepted version of the message did not contain the position of the boat at that time. Dr. Niestle states that the position, grid square AK 96, for U-869 given in BdU's war diary on January 10, 1945 "was probably derived only from plotting the boat since its last reported position.

"After January 10, 1945, no more reports were received from U-869. On January 19 BdU informed the boat about his expectation that the operational area ordered on January 8 is reached on about February 2. On February 17, the BdU attributed reports about the torpedoing of Allied merchant vessels in the Gibraltar area, intercepted by the German Radio Intelligence Service ( B-Dienst ), to U-869. He was, however, unaware ... that U-300 ... was responsible." On February 22, 1945 U-300, under the command of Hein, was depth charged by the British warships Recruit, Evadne, and Pincher, and sunk southwest of Cadiz and therefore did not report the sinkings attributed to U-869.

All U-boats carried grid-covered charts ( duplicates of those at U-boat headquarters. ) U-869 was ordered to go to grid CA 53. The grid system allowed U-boat command to deploy U-boats without fear of enemy interception of the orders. In turn, the U-boats could keep headquarters informed of their locations without giving the information to the enemy.

Dr. Niestle continues, "Despite the absence of any conclusive information about U-869 after January 10, the BdU believed the boat to have operated in its assigned area ( off Gibraltar ) until depletion of fuel and provisions forced the boat to commence the return passage. Owing to the common practice of operational boats not to give away their position by radio signals for fear of being located by radio direction, BdU apparently saw no reason for expressing anxiety about the fate of U-869. Assuming the boat was already on its home-bound passage, he informed it on April 2, 1945, that Kristiansand-South would be its port of destination, thus expressing his intention for subsequent onward transfer to Germany for yard overhaul. When the air defense situation in the Kattegat area deteriorated drastically during April 1945, this order was canceled on April 24 and U-869 was ordered to go to Bergen."

U-869 did not arrive at Bergen and did not surrender at the cessation of hostilities. In June 1945, the German Naval High Command prepared a "List of Lost U- boats" ( PG 13953 ) and assumed U-869 was lost on or about February 20, 1945, while still operating off Gibraltar. However, this was speculation and was probably based on the B-Dienst report of U-boat activity in that area.

After the war, the Allied Antisubmarine Assessment Committee listed U-869 as being lost on February 28, 1945, in the area west of Rabat, Morocco ( 34'30' N, 08'1 3'W ). The U.S. destroyer escort Fowler and the French patrol craft L'Indiscret were credited with sinking the U-boat with depth charges. Fowler picked up a sonar contact while escorting convoy GUS 74. The contact was attacked with 13 magnetic depth charges which brought lumps and balls of heavy oil sludge to the surface after five or six explosions. A second attack with 12 magnetic charges dropped in the middle of the oil sludge resulted in two more explosions, but no further evidence of damage. Later, a L'Indiscret attack on a sonar contact in the same area caused a large black object to break the surface; it sank immediately, but no debris was observed and contact was lost. In the absence of any other explanation of the loss of U-869, the Committee credited both ships with a kill.

'U-Who' Identified

Dr. Niestle, referring to the knife found by Captain Chatterton states, "The inscription (Horenburg) was almost certainly used to identify the knife as property of a crew member with the same family name. The casualty list of the German U-boat Arm in World War II lists only a single person with the inscribed name. His name was Martin Horenburg, born on October 1, 1919, and recorded as lost on U-869 while serving as Funkmeister on this boat."

Dr. Niestle continues, "Although this information apparently does not fit into the picture, as U-869 is recorded as lost in the Gibraltar area or at least in the Eastern North Atlantic, there can be no doubt about the identity of the wreck found being that of U-869. Apart from the fact that Horenburg was the only U-boat crew member with this name lost in the war, it now becomes clear that U-869 did not receive the BdU order to steer for the Gibraltar area instead for its originally assigned steering area CA 53. The difficulties to send or receive messages by radio in early January 1945 in the Atlantic have become obvious from the repeated difficulties to obtain reports from U-869 during that period. It is therefore not surprising that U-869 did not receive the message about the change of its operational area and continued on its original route. Moreover, the position of the wreck is almost identical with the steering area CA 53 assigned to U-869 on December 29, 1944, by BdU. It is therefore very likely that U-869 operated in this area, taking it as her intended operational area in the absence of the reception of any other orders contrary to this.

"Assuming a normal direct transfer route across the Atlantic from the point where U-869 reported its position for the last time on January 10, 1945, it is likely that U-869 arrived in CA 53 on or about February 1, 1945. At that time U-869 would have been already 55 days at sea. Taking into consideration the time necessary for the return passage ( at minimum 40 days ), it seems likely that U-869 would have commenced its return passage at the end of February 1945 or early March at the latest in order to complete its patrol within the usual patrol length for snorkel operations off North America in 1944/45. Patrols did not exceed 123 days ( U-1230 ) during this period, but almost generally lasted more than 100 days. With reasonable certainty, it is likely that U-869 was lost in February 1945. However, the reason for its loss remains speculative, as there are no recorded antisubmarine attacks during February / March 1945 in the vicinity of the wreck's position.

"However, the following incident might give a possible explanation for the loss of U-869. On February 17, 1945, the U.S. tanker Harpers Ferry reported sighting a submarine in 38 58' N, 72 25' W and seeing a flare off her starboard quarter, after which there appeared to be an explosion on a vessel astern of her. If the object sighted by the tanker was indeed a U-boat, the explosion could well have been due to a torpedo, which, since no ship was in fact reported torpedoed at this time, may have either exploded in the seaway or in the target's wake or have run back ( a circular run ) and hit the U-boat. Although the position of the incident is some 50 miles distant from the wreck location, the position in Harpers Ferry radio room may well have been three hours old, depending on how often it was updated. Hence the ship's true position could feasibly have been in the vicinity of the wreck's position, which lies close to the tanker's track into New York, to where she was bound from Cristobal and Cartagena. Because the U-boat wreck found shows extensive damage in its mid-section, the destruction may have resulted from one of U-869's T-5 homing torpedoes that ran back."

Thanks to the recovery of Funkmeister Martin Horenburg's inscribed knife by Captain John Chatterton and Dr. Axel Niestle's interpretation of events, " U-Who" has regained her identity as Germany's Type IXc U-boat U-869. More supporting evidence will come to light as divers continue to explore the World War II relic.