Relentless

- Type:

- artificial reef, tugboat

- Built:

- 1950, Gulfport Shipbuilding, Gulfport Shipbuilding Corp, Port Arthur, TX USA

- Specs:

- ( 102 ft ) 197 gross tons

- Sunk:

- Tuesday November 26, 2019 - 12-Mile Artificial Reef

- Depth:

- 125 ft

- GPS:

- 40°37.104' -72°31.388'

Esso Tug No. 9

Standard Oil's First Diesel Tug in New York Harbor

From PACIFIC MARINE REVIEW,

Volume 46, OCTOBER 1950

ONE of the largest privately owned merchant fleets in the world serves petroleum exclusively, and sails under the Esso house flags of the various Standard Oil Company ( N.J. ) affiliates. The major part of the fleet consists of oceangoing tankers up to 26,000 tons deadweight each. There are also a host of smaller craft, including LST's in offshore drilling, and tugs used for barge hauling and for docking their big sisters. In the New York harbor area, the Inland Waterways Division of the Esso Standard Oil Company has eight tugs docking and undocking ocean-going oil carriers, and towing barges.

But it was only in recent weeks that Standard Oil acquired its first Diesel-Electric tug for domestic operation, Esso Tug No. 9. Built by the Gulfport Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company, she is the latest of a long series of General Motors Standardized tugs of about her size and power, from which "bugs" often associated with new design have been eliminated as the result of hundreds of thousands of miles of heavy-duty service in many parts of two hemispheres, to which these little vessels have gone under their own power.

Esso Tug No. 9 is owned by the Esso Standard Oil Company (Inland Waterways Division), operating and marketing affiliate of the Standard Oil Company (N. J.). Her maiden trip from Port Arthur to Hudson River - a distance of 1829 nautical miles, buoy to buoy - was made in six days and eight minutes, or an average speed of 12.69 knots. The weather was moderate, but occasional squalls were encountered.

The main engine of the vessel is a General Motors Model 12-278A Diesel, which develops 1200 b.hp. at 750 r.p.m. It drives an 814-kW., 560-volt, 1454-amp., d.c. generator that furnishes current to the electric propelling motor turning at 875 r.p.m., but geared down to the propeller shaft, the latter turning at 200 r.p.m., at full speed, and delivering approximately 1050 shp. to the propeller. There are 12 V-arranged power cylinders, each 8.75" in diameter by 10.5" stroke, operating on the two-cycle principle.

Esso Tug No. 9 is completely packed with power, for her main engine and generator together are less than 25 feet long by 6 feet wide. This small overall size for 1200 bhp. allows ample room in the machinery compartment for the auxiliary equipment, fuel, and lube oil tanks, and for the engine room crew to move around freely.

The vessel has an overall length of 102 feet. Her mean breadth is 25 feet, and her molded depth 12 feet, 4 inches; while the molded draft is 10 feet, 1 inch. She is registered at 192 gross tons and 82 net tons. She was designed by Tarns, Inc., New York City, in cooperation with the builder's engineering department.

A crew of ten is carried. They work 12 hours (six on and six off) for 20 days, then go ashore for 10 days, a substitute crew taking over during that period. The permanent crew consists of captain, mate, chief engineer, assistant engineer, cook, four deckhands and a day man.

The skipper's quarters are located in the after part of the pilothouse.

On the main deck, the mate's quarters on the port side has two berths, and the cook's cabin to starboard has one berth. Alongside the cook's cabin is the companionway to the crew's quarters below, where there are six berths, or more than sufficient for the present crew. Next on the main deck comes the galley, then a toilet and shower, and the engine room opening with its entrances to the two engineers' cabins, one of which has two berths.

The entire tug is equipped in a modern way and includes radar, direction finder, and radio-telephone system.

USCG HISTORY

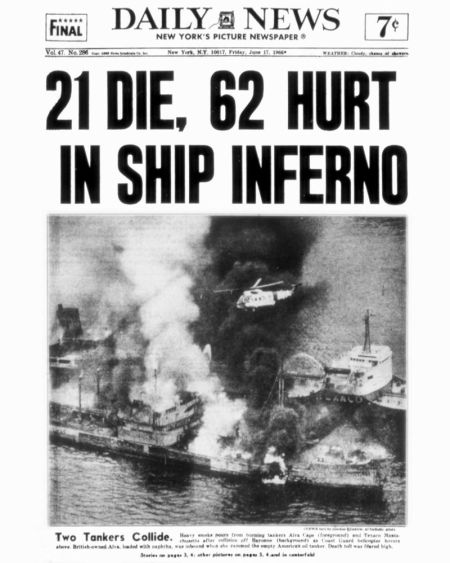

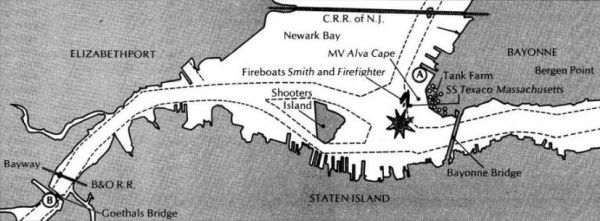

On this day, June 16, 1966 -The freighter Alva Cape and tanker Texaco Massachusetts collided in New York Harbor near Third Coast Guard District Headquarters on Governor's Island. Thirty-three crewmen perished in the ensuing explosion. Coast Guard units responded and the rescue effort garnered significant national media attention.

Fiery Tanker Crash At New York

By James Donahue

Errors in judgment by the navigators aboard two tanker ships carrying volatile cargos resulted in a collision, explosion and fire that consumed both tankers, two attending tugs and left 37 sailors dead and more than 20 injured in New York harbor on June 16, 1966.

The fiery accident remains counted even today as among the deadliest shipwrecks in the history of New York Harbor.

The British MV Alva Cape was entering the harbor with a cargo of naphtha and was struck amidships on the starboard side by the outgoing American tanker Texaco Massachusetts. The raging explosion and fire that resulted from the crash destroyed not only the tankers but the tugs Latin America and Esso Vermont.

Thirty-four sailors perished during this first explosive event on July 3. Nineteen of them perished on the Alva Cape, eight ** on the Esso Vermont, three on the Texaco Massachusetts and three on the tug Latin America. The U.S. Navy, Coast Guard and New York City fire boats worked together to battle the flames and rescue as many sailors as possible from the burning vessels in a place with the ominous name of Kill Van Kull Channel.

The blaze was finally extinguished, but the Alva Cape was not finished as a human death trap. Three more men were killed in yet another explosion while they were aboard the burned out wreck, attempting to unload what remained of its deadly cargo. This happened just 12 days later, bringing the death toll from the accident to 37.

During subsequent litigation and hearings it was learned that the crew of the Texaco Massachusetts worried about a possible collision as the two vessels approached each other in what would have involved a harbor crossing. The larger 604-foot Texaco Massachusetts reversed engines and attempted to back as the 546-foot British tanker approached. It was determined that if the American tanker had maintained its speed and taken no action, it would have safely passed and averted the crash.

After the second explosion, the Coast Guard towed the Alva Cape 110 miles out to sea and then shelled the ship until it blew up once again and sank.

** Editor's Note:

There were no survivors on the Esso Vermont. The tugboat was actually caught between the two burning tankers. Alva Cape was sunk in 1200 fathoms of water off Cape May.

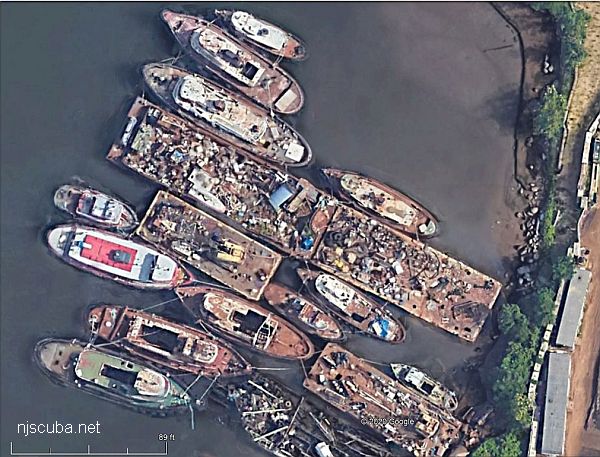

By 1967, the Esso Vermont was back in service as Phoenix. I don't know what to think of that name. The earliest identifiable imagery of her at the tugboat graveyard is 2010, possibly as early as 2004. At one point in 2016 Relentless was slated to go to the Shark River Reef.

The Tugboat Graveyard

Questions or Inquiries?

Just want to say Hello? Sign the .