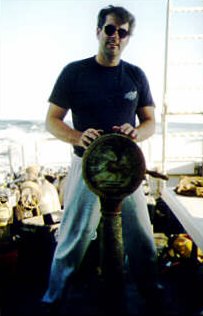

Engine Telegraph

Recovery of the Docking Telegraph of the Carolina

by John Chatterton

photos by Pat Rooney

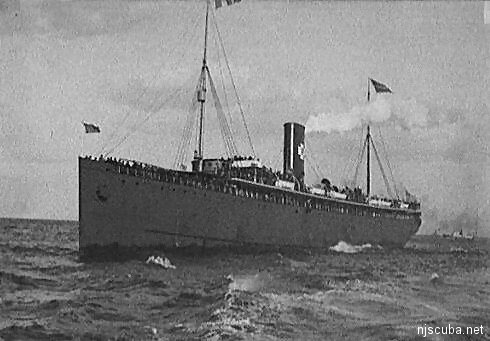

On June 13, 1995, I was diving the Carolina from Paul Regula's Bounty Hunter. It was my fifth dive on the wreck, a beautiful day, and I was looking to do some sightseeing. I went down to do the tie-in and found enough current that I thought about hanging near the anchor line, but decided instead on shooting video as far as I could go. We were tied into the wreck about 50 feet forward of the stern, and I proceeded to swim all the way to the bow. On the way back I was a little winded, and running a little late, when I noticed what I believe is the Purser's safe. I shot what video I could and had to get a move on.

For my second dive I felt that I wanted to be pretty conservative and not travel all the way back to the purser's safe again, but instead work on removing more of the brass letters across the fantail. I had already removed the letter "C" on a previous dive, and we were tied in pretty close so I wouldn't have to do much more in the way of swimming. I went down and the current was blowing pretty good. I was glad I hadn't planned on going very far. I removed the "A", and the "R", from Carolina and the "N" from New York. My goodie bag now weighed a good 60 pounds or more and I put a lift bag on it. I wanted to stay down low out of the current as much as possible and swim the bag up to at least to the anchor line so the bag would surface close to the boat.

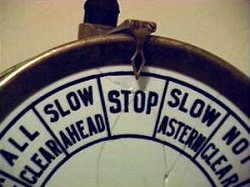

As I was moving along, I noticed what looked like a pipe flange, but obviously made of brass. I stopped and started to cut away fishing nets and monofilament until I had exposed a telegraph and its pedestal! I could even see writing behind the cracked glass. It was beautiful. I dragged it further out into the sand but was unable to cut the telegraph chain to entirely free it from the wreck, and I was out of time. I shot my bag with the letters in it and had a lot to think about on the hang. On Labor Day, I made my way back to the telegraph and brought it to the surface.

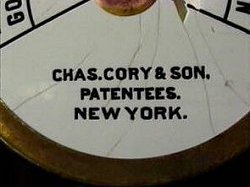

When I got it home, I cleaned it up and immersed it in freshwater for a little over 3 months. The single handle was made of wood and was still intact. After the freshwater rinse, I carefully dried the handle and applied linseed oil. It is worn but still intact and not so much as a crack. I disassembled the brass components and cleaned them with a vinegar bath. I then polished and reassembled them. The face was made of white milk glass with the lettering etched into the glass. The milk glass was cracked and broken, but I had almost all the pieces. The milk glass was water and rust-stained which I cleaned with Wink Rust Remover. Most of the black paint from the letters washed off and it was relatively easy to touch up the etched letters after I glued together the 50 or so pieces. Over the milk glass was a plate of clear glass, most of which was lost on the wreck. I replaced the clear glass rather than attempt to restore only half the original.

The telegraph was used to relay information from the helm to the engine room and back again. The officer at the helm could control the maneuvering of the ship in this way. The telegraph that I recovered was from the stern docking station and was used to communicate with the engine room and the bridge when bringing the ship into its berth. The commands on the face are those needed for docking the ship. The single handle is for the single engine. This telegraph replaced the original two-handled telegraph that the ship was built with when it was refitted in 1914. It weighs about 75 pounds.

Original NJScuba website by Tracy Baker Wagner 1994-1996