Arrowheads

Bits of Ancient Village Hide in Murk

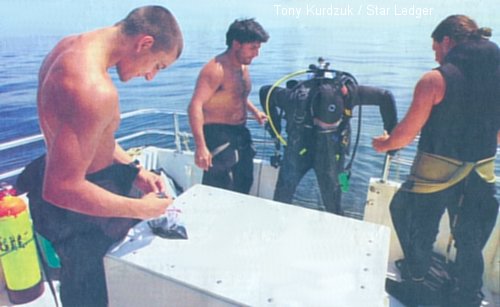

A team of archaeologists in scuba gear combs what was once dry land for pre-Lenape artifacts

Tuesday, August 26, 2003

BY KELLY HEYBOER

photos by Tony Hurdzuk

Star-Ledger Staff

Fifty feet below the surface of the Atlantic, Greg Porter knelt on the ocean floor and began to fan his gloved hand over the sand, looking for evidence of some of the first New Jerseyans. The current created by the slow movement of his hand cleared a small hole next to the bent knees of the anthropology student. As the silt cleared, Porter saw it: a smooth one-inch black piece of ... something. It was too black and porous-looking to be a rock. Encouraged, Porter and his diving partner placed the object in a plastic bag. Soon they started the slow ascent through the murky water back to the surface. There an archaeologist reinforced Porter's hopes. The object was probably a charred mammal bone - perhaps the leftovers of a 10,000-year-old lunch of one of the first residents of the Jersey Shore.

It was one of the early finds of an unusual archaeology project unfolding in the waters off Sandy Hook. On this spot, one mile east of the Twin Lights Lighthouse, underwater archaeologists believe they have discovered the water-covered remains of a 10,000-year-old village first occupied by the predecessors of the Lenni Lenape tribe. "It's the primordial Jersey Shore, " said Daria Merwin, an underwater archaeologist overseeing a group of college students spending the summer exploring the area. The site was discovered by accident in the mid-1990s after the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers dredged the area and deposited the sand at Monmouth Beach and Sea Bright.

A regular beachcomber traversing the newly deposited sand began picking up what appeared to be arrowheads. She brought them to the attention of an archaeologist at Gateway National Recreation Area, the national park that includes Sandy Hook. Eventually, more than 200 arrowheads and remnants of stone tools were discovered on the beach, some dating at least 8,000 years. "At some point during the dredging, they dredged up a prehistoric site, " Merwin said. "It's just the luck of the draw that this woman picked up everything." Using the Army Corps' dredging maps, archaeologists were able to determine a 9,000- by 1,000-foot swath of ocean floor where the artifacts probably originated.

Merwin, project director at the Institute for Long Island Archaeology at the State University of New York at Stony Brook, assembled a group of about a dozen college students and volunteers to spend the summer underwater, looking for the remains of the Native American village. The subsurface site is a 45-minute boat ride from the Atlantic Highlands Marina, but thousands of years ago it was prime real estate. From topographical maps of the ocean floor, archaeologists can tell it was once a bluff overlooking a stream that led to the sea.

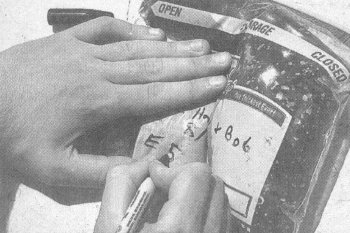

Matthew DeFelice shows a message he has written on a tablet to a diving partner as they prepare to search the holes they have dug.

"My sense was it must have been a sizable site, probably a stream bank that was repeatedly occupied for thousands of years, " Merwin said. Researchers believe the nomadic hunter-gatherer forefathers of the Lenni Lenape spent their summers there, fishing the ocean and hunting inland in a primitive version of a Shore settlement. It is likely the tribe had primitive tools, wove baskets, and lived in versions of a wigwam. The hunters may have returned to the site in the winters when large sea mammals came close to the shore or stranded themselves on the beach.

Proving these theories will not be easy. As the students learned this summer, underwater archaeology is difficult and painstakingly slow. Most days, finding the remains of a charred bone or a sliver of a stone tool in the frigid, murky waters at the bottom of the Atlantic is a major success. The largely barren ocean floor yields few clues to where artifacts may be buried, said Charlotte Hjarthner, an underwater archaeologist from Sweden who volunteered to travel to New Jersey to be part of the project. Unlike in warmer waters, there are few landmarks and little visibility.

"It's like a desert - sand, sand, sand. A few rocks, " said Hjarthner, 33, as she prepared to put on her wet suit. "If you find something, you have to hold it up to your face." the students, all required to be experienced scuba divers to join the project, visit the ocean floor in teams of two. The divers gather at the boat's anchor, which has been dropped at predetermined coordinates. Each team is assigned a direction from the anchor ( north, northeast, east, and so on ) to follow, and uses an underwater compass and tape measure to measure out 50 meters from the anchor.

The teams dig a hole every 10 meters along their tape measure. By "fanning" -- waving their hands near the bottom - they create a small current that clears the sand. Once the silt clears, they have a small hole in which only heavy objects, like artifacts and stones, remain. Telling the difference between a 10,000-year-old artifact and regular-old garbage is often impossible on the ocean floor, said Matthew DeFelice, 26, a Monmouth University graduate from Colts Neck. The divers pick up anything that looks interesting, place it in a plastic bag and bring it to the surface.

The waters off Sandy Hook contain the remains of centuries of boat traffic, as well as some evidence of the years when Sandy Hook was an Army testing ground for weapons, in the late 1800s and early 1900s. "We keep finding a lot of coal, which is probably from the steamboat traffic, " De Felice said. "And ammunition shells. We don't touch them." Everything that is found is carefully labeled and cataloged. Carbon dating and additional testing will help determine the exact age of any promising finds.

Promising Items bagged by divers are cataloged for future testing.

Next year, Stony Brook researchers hope to make a precise map of the ocean floor in the area, if funding permits, using a form of sonar called multibeam swath bathymetry. That should help target exactly where the village was. Despite the slow progress, the students say they are having fun. The group ( individuals paid up to $2,150 in tuition and an $800 fee to participate in the project ) lives together in an old Army barracks at Sandy Hook's Fort Hancock.

In between dives, they sit on the boat deck listening to Jimmy Buffet, eating peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, and teaching the visiting Swedish archaeologist how to say "fuhgeddaboutit" like a native. Except by the occasional curious boater slowing to have a look, the project goes largely unnoticed. Other than an empty bleach bottle acting as a buoy, nothing marks the site, and the archaeologists are reluctant to discuss its exact location for fear of amateur divers pillaging the area.

Most of the boaters in the area would never guess they are floating over the remains of a prehistoric village, said Mick Trzaska, the veteran captain of the CRT II, the Atlantic Highlands-based charter boat shuttling divers to the site. "I'd never think of that. I'm out here looking for fish. Not rocks, " Trzaska said.