Maritime Salvage Law (1/3)

LOST AT SEA:

A treatise on the management and ownership

of shipwrecks and shipwreck artifacts

by Michael C. Barnette

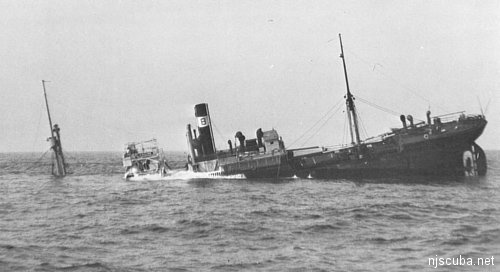

Somewhere out on the ocean, a ship is in distress. Tossed about by churning seas and brutal winds, the vessel struggles to stay afloat. Her crew puts forth a valiant effort while passengers, many incapacitated by waves of nausea spawned by the ever-moving deck underneath their feet, huddle together in fear. The hull is slowly breached, and seawater steadily invades the ship. As the blitzkrieg of flooding water rises to extinguish the boiler fires, the vessel loses all power. Cast in darkness and overwhelmed by the noise of the howling wind and crashing surf, the sea tears off sections of the crippled ship, carrying away numerous unfortunate souls. The end is near.

As the bow of the vessel slips beneath a wave, the flood of water inside the ship rushes forward. With building momentum, the stern rises skyward. Barely discernable above the crescendo of the wind and waves, horrific noises permeate from within the hull as machinery breaks loose and bulkheads collapse. Propagating away from the sinking ship is a ring of flotsam and debris, sporadically punctuated with both terrified survivors and the broken bodies of the deceased. The ship makes its final plunge while escaping air hisses loudly as it is forcibly expelled from the hull. The stern quickly follows the remainder of the ship, disappearing beneath the waves. All that remains to mark the hasty departure of the vessel is a river of debris bobbing along the surface.

A shipwreck does not just result in the initial emotional and economic impacts that frequently emblazon newspaper headlines. A shipwreck is a time capsule - history captured in twisted steel, eroded wood, and countless artifacts that can reveal important information about a former way of life. Yet, a shipwreck can also be a navigational obstruction, an ecological oasis, a hazardous waste site, or an economic venture. Regardless of what a shipwreck may represent, numerous interest groups including divers, archaeologists, and salvors frequently find themselves at odds in regards to the management of shipwreck sites. Just as the crew fought to save their ship from being consumed by an angry ocean, divers may soon need to battle against a wave of bureaucratic red tape that could prevent future shipwreck exploration efforts; hopefully, the wreck diving community won't also be lost at sea. In order to learn more about the issues surrounding shipwreck management, one must first address the complicated issues of shipwreck ownership.

FINDERS, KEEPERS ?

The law of salvage and the law of finds are the two principal aspects of admiralty law that provide legal guidance for how the issue of shipwreck ownership is approached. When property, such as a vessel and its cargo, is lost at sea, salvage law generally applies. Under the law of salvage, salvors take possession of, but not title to, the distressed vessel and/or its cargo. Subsequent to the salvage of a vessel or cargo, a court awards the salvors a reward depending on various factors, such as the value of the salvaged property, the risk involved, and the overall success of the salvage effort.

Historically, salvage was promoted as a means to rescue imperiled property in order to return it to the lawful owner and the stream of commerce. Recently, emphasis has also been placed on the elimination of navigational hazards and the reduction of potential environmental impacts such as pollution and habitat degradation. As the law of salvage is intended to encourage rescue, when a ship is in distress and has been deserted by its crew, anyone can attempt salvage without the prior consent of the ship's owner.

Obviously, salvage law is fairly straightforward for contemporary maritime accidents where the current owner is easily identifiable. In many cases, a salvage company negotiates with a shipping company or its insurer prior to conducting any salvage effort. However, for shipwrecks that have been immersed for long periods of time ( and with no owners immediately apparent ), a salvor files an admiralty claim by having the court physically "arrest" the wreck until an informed judgment by the court can be made.

Typically, an admiralty arrest is done by proxy, with the salvor presenting an artifact to the court that is representative of the shipwreck as a whole. Notice of this claim gives any potential owners the ability to assert their ownership rights and negotiate a reward for any saved material. The owner can also decline the benefits of salvage. In the latter case, this could be interpreted as the owner expressly declaring abandonment of the shipwreck and/or its cargo. However, as noted in International Aircraft Recovery v. The Unidentified Wreck and Abandoned Aircraft, 218 F.3d 1255 (11th Cir. 2000), it is appropriate for an owner to reject salvage assistance in the context of historic wrecks so that the title holders can prevent salvors from raising long-submerged vessels. As we will see, there are many other contradictory and confusing areas of admiralty law.

If a vessel or property is abandoned at sea, the law of finds traditionally applies. The law of finds can succinctly be summed up as "finders, keepers." That is, whoever finds and recovers the abandoned property can become its new owner. Frequently, it is assumed that if a shipwreck has remained on the seabed and forgotten for an extended period of time that the vessel would be abandoned. Abandonment was therefore implied, especially in the case of an owner who never asserts control over a shipwreck or otherwise indicates any claim of possession. Recent court decisions have upheld, however, that time alone does not relinquish ownership, but rather only abandonment by express acts. It was determined that an owner may come forward at any later date to indicate his or her claim of possession and, as such, abandonment cannot be implied.

This was most notably illustrated in Columbus-America Discovery Group v. Atlantic Mutual Insurance Company, 974 F.2d 450 (4th Cir. 1992), which stated that should an owner appear in court and there be no evidence of an express abandonment, title to the shipwreck remains with the owner. Obviously, issues of abandonment are more often raised over shipwrecks that have the potential to hold some significant salvage value, such as the case of the gold-laden S.S. Central America in the aforementioned lawsuit. It is not likely to become an issue over the numerous shipwrecks that are of little economic value to the prospective salvor.

So, for example, a diver exploring the wreck of the World War II tanker S.S. Cities Service Empire, which rests in 240 feet of water 30 miles off the coast of Florida, recovers a porthole. Since the identity and location of this wreck have been known for a lengthy period of time, and since the owner has not asserted ownership rights over this shipwreck, one might incorrectly assume an inference of abandonment. This inference could be supported by the fact that, in this particular example, salvage activities were reported on the front page of the Wall Street Journal.

However, although the owners may have tacitly permitted past salvage due to apathy, it does not necessarily relieve the diver of his or her responsibility for filing an admiralty claim to clearly secure ownership of the artifact and/or the shipwreck itself. In the absence of an admiralty claim, a recovered artifact could be "repossessed" by the rightful owner in the future. However, if the vessel owner desired to assert control over the shipwreck and its associated artifacts at a later time, the owner would need to negotiate an appropriate award with the diver through the court for any salvaged items.

Since many commercial World War II casualties, such as the S.S. Cities Service Empire, were declared constructive total losses, the original owners actually abandoned the vessels to their insurers. So, in this case, Lloyd's of London would retain the title of the S.S. Cities Service Empire.

A constructive total loss occurs when either:

- The insured vessel is reasonably abandoned on account of its actual total loss appearing to be unavoidable, or because it could not be preserved from actual total loss without an expenditure which would exceed its value;

- where the insured is deprived of the possession of the insured property by a peril insured against and it is either unlikely that he can recover it or too costly to attempt to do so; or

- where repairing the damage to the insured property would be too costly.

An actual total loss occurs when either:

- The insured property is completely destroyed;

- The assured is irretrievably deprived of the insured property;

- cargo changes in character so that it is no longer the thing that was insured (e.g., cement becoming concrete); or

- a ship is posted missing at Lloyd's, in which case both the ship and its cargo are deemed to be an actual total loss.

Clearly, asserting ownership on many of the commercial vessels ( i.e., freighters, tankers, etc. ) that were wartime casualties is not an economically viable or prudent course of action for Lloyd's, given the fact that there is no significant economic value in many of these shipwrecks. Therefore, it is unlikely that an owner of a wrecked commercial vessel would pursue a claim over a single porthole or other artifact. So, for the numerous nineteenth- and twentieth-century merchant vessels that have become popular wreck diving destinations, it is fairly safe to assume that artifact collection is an allowable activity in the absence of specific legislation or regulation stating otherwise.

EXCEPTIONS TO the RULE

There are a couple of glaring exceptions to the law of finds and the law of salvage in the United States that divers should be aware of, the first of which appeared in the form of the Abandoned Shipwreck Act of 1987. In one swift action, the United States government asserted ownership to all abandoned shipwrecks in state waters ( out to three miles on the Atlantic and Pacific coasts, out to either three or nine miles in the Gulf of Mexico, and throughout the United States portion of the Great Lakes ) through the Abandoned Shipwreck Act. However, the Abandoned Shipwreck Act, which essentially eliminated both the law of finds and the law of salvage of abandoned shipwrecks in state waters, transferred title to all abandoned wrecks in state waters to the respective states, some of which have management policies that facilitate shipwreck exploration and identification, and permit artifact recovery (e.g., South Carolina).

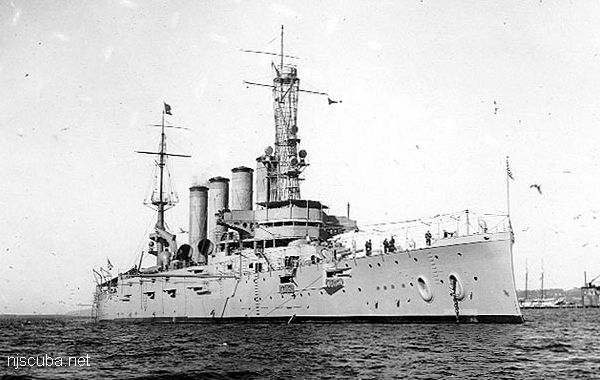

The other important ownership issue to be considered involves those shipwrecks entitled to sovereign immunity. Sovereign shipwreck property encompasses warships and other vessels used for military purposes at the time of their sinking. This would include naval vessels of any nation, including German U-boats, Confederate States Naval warships, Colonial privateers, and Spanish galleons. Further, this includes both naval warships sunk by accident or belligerent action, such as the U.S.S. Schurz or the U.S.S. Jacob Jones, as well as those disposed of in tests or sunk as an artificial reef, such as the U.S.S. Wilkes Barre.

President Clinton's Statement on United States Policy for the Protection of Sunken Warships (January 19, 2001) succinctly sums up the issue of sovereign immunity:

"Pursuant to the property clause of Article IV of the Constitution, the United States retains title indefinitely to its sunken State craft unless title has been abandoned or transferred in the manner Congress authorized or directed. The United States recognizes the rule of international law that title to foreign sunken State craft may be transferred or abandoned only in accordance with the law of the foreign flag state."

Since sunken U.S. Navy vessels are federal property, according to U.S. Code (18 U.S.C. 641), technically no portion of a government wreck may be disturbed or removed, and any unauthorized removal of any property from a U.S. Navy wreck is illegal.

According to the principle of sovereign immunity, foreign warships sunk in United States' waters would be protected by the United States government, who would act as custodians of the sites in the best interest of the sovereign nation. Other countries generally acknowledge this principle as well. For example, the C.S.S. Alabama, as a Confederate States Navy warship, became the property of the United States following the end of the Civil War. While it was sunk off the coast of France, it is still recognized as United States property. Likewise, the H.M.S. Fowey, a fifth-rate British warship sunk of the coast of Florida, still remains the property of the United Kingdom. Yet, it should be pointed out that in some situations even foreign governments do not play by their own rules and respect the principle of sovereign immunity.

In the case of the C.S.S. Alabama, the French government proceeded to excavate the wreck and recover artifacts following her discovery in 1984. It was not until October 1991 and after extensive negotiations that the French government conceded ownership of the warship to the United States, and recovered artifacts were exported to the Naval Historical Center at the Washington Navy Yard. Similarly, the aforementioned H.M.S. Fowey was also subjected to potentially unauthorized excavation, in this case by the National Park Service.

In fact, when the H.M.S. Fowey was included in the National Register of Historic Places on December 4, 1990, it was erroneously stated in the Federal Register that the "wooden British merchant vessel" Fowey was "owned by the U.S. Government." While the National Park Service had the jurisdiction to act as custodian over the site, they definitely did not own it. Even with a custodial jurisdiction, it would appear that the National Park Service would still have been required to request permission from the United Kingdom's Ministry of Defense to conduct the several excavations that have since been completed. Further, instead of returning the collected artifacts to the rightful owners of the warship, they are housed in at least three repositories in Florida and Texas.

Regardless of the official party line, the U.S. Navy sometimes offers hypocritical advice in regards to the collection of artifacts from military shipwrecks. In the case of the U.S.S. Murphy, a destroyer that was involved in a 1943 collision at sea that resulted in her forward half being lost off New York, the United States Naval Historical Center recommended that artifacts could be collected from the then-unknown wreck and used to identify the vessel. In fact, it was the recovery of a gauge with the destroyer's designation number that ultimately led to the wreck's identification and revelations into the vessel's tragic involvement in a largely unknown maritime accident. Subsequent events led to an official U.S. Navy investigation into diving activities on the wreck, whereupon they requested that all recovered artifacts be turned over to the U.S. Navy.

This author can support this policy reversal in regard to the recovery of artifacts off U.S. Navy shipwrecks. While researching the wreck of a destroyer escort in shallow water off Key West, I contacted the United States Naval Historical Center. The vessel in question was used as a target for U.S. Navy aircraft for over five decades, yet there was no easily accessible record of her true identity. When I contacted the Center in hopes of obtaining records of warships designated and used as targets, one of their historians suggested that I should recover a plaque or gauge that could be used to identify the wreck. When I mentioned that such actions are considered illegal and against official U.S. Navy policy, the historian attempted to end the call as soon as possible. Further, I was unable to obtain any archival assistance that would lead to the identification of this shipwreck.

LOST AT SEA ?

Obviously, both express and implied shipwreck abandonment is not always clear, especially in cases of shipwrecks possessing potentially valuable cargo. Even government agencies and professional archaeologists find it hard to determine what constitutes abandonment. For instance, when asked about the recovery of artifacts from abandoned shipwrecks, Dr. George F. Bass, Professor Emeritus with the Institute of Nautical Archaeology at Texas A&M University states, "I am not a lawyer, and thus I do not know how anyone gets salvage rights to an abandoned shipwreck. In fact, I do not even know how it is legally determined that a wreck has been abandoned. When I was a child, my family had a sailboat in the Severn River that eventually sank through neglect. It was, therefore, abandoned by my family, but was it legally abandoned immediately?"

As detailed earlier, abandonment can only occur through an express act. Therefore, the Bass family sailboat would not technically be abandoned unless they filed a claim with an insurance agent and notified any associated permitting agency. This also introduces an interesting aside. In many cases, the sinking of a vessel, whether premeditated, accidental, or through neglect, does not simply absolve the owner's responsibility of addressing current or future potential environmental impacts. It should be noted that due to increased environmental resource protection, owners of a sunken or derelict vessel might still be held financially liable for any potential cleanup or removal. If the vessel is a hazard to navigation or is leaking oil or other pollutants, the United States Coast Guard or the Army Corps of Engineers has the authority to remove the derelict property and fine its owners. In other cases, specific state resource agencies have derelict vessel removal programs that hold owners liable for at least a portion of the cleanup effort. Regardless, in many cases, litigation in Federal court is the only definitive way to determine the parameters of abandonment, and that typically is on a case-by-case basis.

UNDERWATER JUNKYARD,

CULTURAL GOLDMINE,

OR HALLOWED GROUND ?

Resource management is a funny thing. Obviously, one does not actually manage a particular resource, such as a shipwreck. Instead, one manages the actions of individuals who may interact with a particular resource. And because management basically is about dictating about what one can or cannot do, individuals sometimes offer their disapproval when they are potentially affected, especially when the action appears arbitrary or ill-conceived. However, in order to properly establish the most prudent management scenario for a particular resource, consideration should first be given to the resource.

When establishing a management scenario for a shipwreck, one should consider, among other issues, the particular environment in which the wreck resides, as well as the wreck's significance. The loss of life associated with a shipwreck event is also a management consideration and one that has been utilized as an emotional trump card to prevent total access in some situations. The following is an attempt to discuss these issues in a rational manner. If nothing else, it should be apparent after this discussion that there is no one ideal management scenario for all shipwreck sites.

As any diver knows, the marine environment is extremely diverse. Some areas are subject to extreme fluctuations in temperature, current velocity, and weather, while others host placid waters that do not experience a wide range of variation. Generally, the more stable the marine environment, the more favorable it is to a shipwreck's prolonged integrity. For example, one finds typically cold, oxygen-deficient freshwater devoid of wood-eating teredo worms in the Great Lakes ( teredo worms are actually marine bivalve mollusks that feed on wood and other organic material. ) these factors help to preserve wood and inhibit corrosion of iron and steel members found on shipwrecks. Further, while strong winter storms and annual icing impact shallow water wreck sites, the lack of currents and more intense storm systems ( e.g., hurricanes ) allow wrecks in deep water to remain relatively unimpacted.

In addition, the general absence of commercial fishing in the Great Lakes, in particular commercial fishing activities that utilize bottom-tending gear such as trawls and dredges, prevents one anthropogenic impact that can have significant impacts on shipwreck sites. Therefore, resource managers would be prudent to take advantage of these conditions and implement a management scenario that complements the naturally stable environment. In this situation, as with other environmentally protected or relatively stable sites, an in situ ( i.e., objects left in their original position ) approach would appear to be the most appropriate and acceptable management regime.

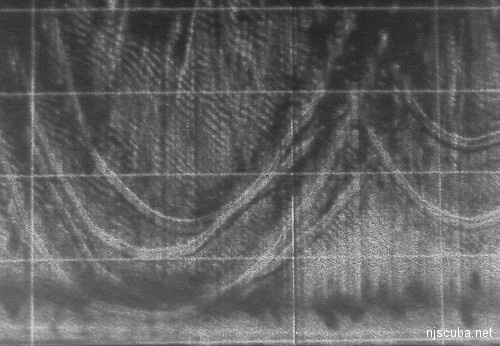

In contrast to the rather stable environment of the Great Lakes, sheltered lagoons, or fjords, shipwrecks in more dynamic areas, such as the exposed offshore waters of the continental shelf ( e.g., the United States Eastern Seaboard ), can be significantly impacted. While deep-water sites are generally not exposed to the same harsh oceanic processes that occur along the continental shelf, the force of a hurricane can have a profound effect on shipwrecks in water as deep as 200 feet. Shipwrecks have been turned over, ripped in half, moved significant distances along the seafloor, or completely buried by large storm events. The storm surge from an intense singular event can rapidly deteriorate the structure of a shipwreck. Furthermore, strong currents accelerate the collapse of a shipwreck's structure.

For example, the velocity of the Gulf Stream, generally in excess of three knots, creates a significant force on vertical surfaces. Hydrodynamic lift can produce constant stress on deck plates that will eventually compromise their integrity. I have personally witnessed bulkhead support beams on the wreck of a tanker resting in 240 feet of water wildly oscillating due to the influence of a three-knot current. Currents also constantly bathe a shipwreck's metal surfaces with oxygen-rich saltwater, which speeds up the corrosive effect on steel and iron. These natural processes cannot be avoided, and the ocean will eventually reclaim all exposed shipwrecks and many of the artifacts that they possess. However, there are also significant anthropogenic impacts that negatively affect shipwrecks.

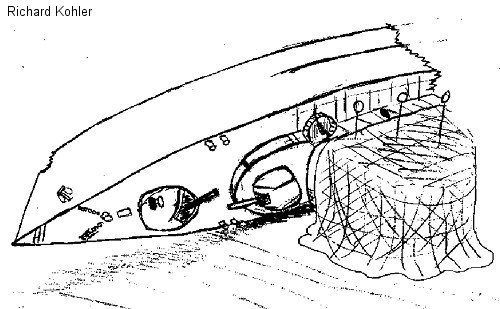

Perhaps the single greatest anthropogenic threat to a shipwreck's integrity is related to fishing activities. Trawling has long been recognized as an agent of physical disturbance that can significantly alter marine habitats. Trawls were developed to allow fishermen to efficiently harvest species that lived in close proximity to the seabed. Nets are towed behind a vessel, which are held open and on the bottom by the hydrodynamic force exerted on trawl doors positioned on either side of the trawl mouth. Introduced to the Atlantic and Pacific coasts of the United States in 1901 and 1905, respectively, trawl gear quickly became an important component of demersal fisheries for shrimp, flounder, cod, and other species. Along with the rich bounty that the sea offers, trawlers, as any experienced wreck diver can attest to, also catch shipwrecks.

Both the heavy trawl doors and the taught ground line impact the seafloor. They create troughs, flatten seafloor features, and re-suspend sediments in sandy and muddy habitats. On gravel, cobble, coral, or other complex habitat areas, trawl doors scrape, damage, and denude vast areas of invertebrate growth. Important deep-water coral areas have all but been eradicated by trawl activity. Even significant bathymetric features have been flattened following years of intense trawling. Hundreds of scientific studies have documented the potential habitat impacts associated with trawl gear. Yet, few, if any, have focused on their impacts related to shipwrecks. In fact, the archaeological community has largely ignored this important issue.

When a trawl encounters a shipwreck, the resultant impact depends on several factors. The size and type of trawl gear, the size and horsepower of the trawler, the composition and orientation of the shipwreck, and the actual purchase made by the trawl gear will all dictate how a shipwreck will be impacted. Trawl doors and ground rope design can vary greatly. Some trawlers use wooden doors, while others use steel. Further, the cables that run from the trawl doors and along the mouth of the net can be fairly rudimentary and adorned with simple chain sweeps, or they can be enhanced with robust rollers that enable them to easily operate on hard, rough bottoms. A trawler's horsepower is an important aspect as well. It takes a powerful engine ( 600+ horsepower ) to pull a large net, especially over rough bottoms. While a large trawler could potentially rip its net free from an entanglement with sheer, brute force, a smaller vessel that does not have sufficient towing power may have to abandon his nets should it get hung up on a wreck.

Clearly, a wooden shipwreck would be more vulnerable to trawl impacts than an iron- or steel-hulled vessel. Lastly, the purchase of the net and the combination of all the above factors will determine the severity of the actual impact. If the ground line gets securely snagged on a vertical steel projection, a fisherman could potentially lose the battle. However, the net could still be worked loose, especially if a strong vessel is towing it. This was illustrated when a passing trawler snagged the wreck of the U.S.S. Moonstone off Ocean City, Maryland, several years ago. The encounter resulted in the large deck gun of the patrol vessel being dragged off the top of the wreck and dumped into the debris field on the seabed. While often it is hard to differentiate fishery-related impacts from the natural aging of a wreck, undoubtedly the cumulative impacts of fishing gear interactions greatly reduce the "lifespan" of a shipwreck.

Obviously, most trawlers do not wish to directly encounter a shipwreck, due to the potential for lost or damaged gear. However, many trawlers know that the seabed in the direct vicinity of a wreck can be very productive, and they purposely operate in close proximity to shipwrecks. In fact, some scallop boats, which tow multiple steel-framed dredges with chain-link mesh bags ( each weighing 1,000-2,000 pounds ) at speeds approaching five knots, intentionally target the wash-out areas around shipwrecks where abundant numbers of scallops can be found. Frequently, there are interactions between these heavy dredges and shipwrecks. There have also been reports from New England indicating that large groundfish trawlers are targeting wooden shipwrecks in order to harvest the abundance of cod and haddock that these wrecks support. In some cases, certain shipwrecks have all but been eradicated by these activities, their timbers widely scattered across the seabed.

In light of the dramatic influences on those shipwrecks that rest in highly dynamic environments, should the random diver be prohibited from seeking a souvenir? Perhaps. While divers, even those armed with sledgehammers and crowbars, certainly have a trivial impact when scaled against the natural impacts of Mother Nature and the wide-scale effects of fishing activities, divers can still have an impact. The removal of a porthole definitely does not have a significant environmental effect, especially considering that brass inhibits invertebrate growth due to the copper content, however, important archaeological information could be lost if artifacts were removed from a shipwreck that was deemed to be historically significant. Archaeologists are quick to make this obvious point. The problem is that, by and large, there really is no good way to determine what constitutes "historically significant."

Many in the archaeological community have approached this dilemma by simply classifying all submerged cultural resources, such as shipwrecks, as being significant. Obviously, this throws the protective blanket far and wide but perhaps is not the most practical solution. As with the diving or salvage community, the archaeological/scientific community is simply one of many user groups vying for the resource. Without a doubt, in some instances, certain shipwrecks should only be investigated and excavated by accredited archaeologists. However, in many other instances, the benefit to society in allowing only the archaeological community access to recover artifacts is negligible. Further, this would basically privatize a public resource to a select group of individuals. Similar to the implementation of marine protected areas to protect fragile ecosystems from damage or vulnerable fish species from overexploitation, society may well indeed benefit more from non-consumptive scientific research than from consumptive utilization of shipwreck resources in some situations.

However, just as closing off the entire ocean would not be deemed prudent or acceptable by any except the most militant environmentalist, prohibiting the utilization of all shipwrecks in the name of science simply does not make sense. Only in the rare marquee archaeological project is the general public made privy to the discoveries made and lessons to be learned from a shipwreck. Therefore, aside from the theses produced by aspiring archaeologists or articles in academic journals, both of which are rarely consumed by the general public, most of the information is retained within the archaeological community. Perhaps British historian George M. Trevelyan summed it up best when he stated: "Since history has no properly scientific value, its only purpose is educative. And if historians neglect to educate the public, if they fail to interest it intelligently in the past, then all their historical learning is valueless except in so far as it educates themselves."

Many entities classify shipwrecks as historical via an arbitrary dating system. For example, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization's Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage and the U.K. Receiver of Wreck use a period of 100 years to classify cultural heritage or to determine if a shipwreck is historical. Likewise, the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary employs a 50-year period to determine if a resource is historical. But, time alone does not dictate significance. If it did, every structure that stood for more than 50 years would be considered historically significant. We would also have to consider our elderly population historically significant. With no offense to senior citizens intended, it should be remembered that sometimes things are just old, and not necessarily significant. The point to get across here is that perhaps a more discrete classification system is in order.

Professional and personal opinions diverge not only in respect to the classification and utilization of shipwreck sites, but also in the philosophical point of view surrounding basic shipwreck access issues. Sometimes, these access issues deal with the potentially incendiary debate surrounding the designation of shipwrecks as gravesites. In most instances, this discussion is focused strictly on military shipwrecks. Legislation has even been passed to protect these "war graves, " such as the Protection of Military Remains Act 1986 in the United Kingdom. I have always wondered why this discussion is not consistently carried across the spectrum of maritime casualties, as I fail to see how any one death at sea can be more significant or traumatic than another.

Regardless, the loss of life stemming from a shipwreck event raises some emotional, ideological, political, and religious issues. In some cases, promoting a shipwreck as a maritime gravesite has prevented total access, such as with the wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald. While the loss of any life is tragic, it should not necessarily prevent resource access or utilization. One should definitely respect the symbolic nature of a shipwreck - that of both economic and emotional loss. In many cases, especially at sites where all traces of human remains have been claimed by the marine environment, symbolism is all that lingers. But should access to shipwrecks that have a loss of life associated with them automatically be closed? Certainly not.

Across the globe, land has been settled and wars have been fought. Unmarked graves are spread far and wide, yet life goes on. Specific individual shipwrecks should definitely be memorialized due to clearly recognized significance, just as society has conserved and protected certain terrestrial sites. But wholesale prohibitions - whether on-site access or recovery of artifacts - should be avoided at all costs. Individuals pushing an agenda commonly refer to wreck divers as "grave robbers" or "looters." While the tactic may work to attract the attention of the crisis-hungry media, it holds no merit in intelligent discourse. Regarding the use of the words looting, pillaging, and plundering, as it applies to legal artifact recovery, Sophia Exelby, U.K. Receiver of Wreck, explains: "These words are not appropriate. They are inflammatory, and do not assist in a rational discussion."

It should also be pointed out that those grave-robbing claims were silent when the turret of the U.S.S. Monitor was recovered and when the Confederate Navy submarine C.S.S. Hunley was raised - both of which contained human remains. Wreck divers no longer recover human skulls and place them in dive shop windows or curio cabinets, just as archaeologists no longer haphazardly recover artifacts from Egyptian tombs and marine biologists and geologists no longer utilize explosives to take samples from coral reefs. While there are very isolated instances of divers dredging out U-boats that contain human remains in order to recover artifacts, that practice is largely condemned within the diving community. Furthermore, as pointed out earlier, that practice is illegal.

One could point out that archaeological projects such as the Monitor and Hunley recover artifacts for the public good. Information is dispersed and artifacts are put on public display, whereas wreck divers hide away their artifacts so the public cannot enjoy them. What the general public does not recognize is the fact that the vast majority of archaeological artifacts recovered are boxed up and housed in vast repositories rather than put on display. Further, many agencies and universities are confronting a "curation crisis, " as in some cases they do not have the space or economic resources to house millions of artifacts; in 1997 the Smithsonian Institution alone housed over 140 million items, of which 122 million were natural history objects.

An article that appeared in Federal Archaeology cited that 30 percent of non-federal facilities have already run out of room to store or exhibit archaeological objects. Space is not the only issue, as conserved objects must be maintained under specific environmental conditions to ensure their preservation. As documented in an American Archaeology article, proper climate-controlled storage appeared to be the exception, rather than the rule. After visiting three universities that stored artifacts from federal lands, a National Park Service archaeologist reported that "In 99.9 percent of the cases, I felt the storage conditions were substandard." the worst example was described thusly: "The collections were in a storage room where overhead pipes leaked onto the artifacts that were in paper bags. The provenience information written on the bags in pencil was unreadable. All the metal artifacts were rusted. All the bone had turned to mush."

Perhaps this was just an isolated example of how academic and governmental agencies care for our cultural resources. Not so according to a 1986 report from the Government Accounting Office (GAO). The GAO report, "Problems Protecting and Preserving Federal Archaeological Resources, " was based on a questionnaire sent to non-federal repositories that housed federally owned collections. The results were shocking. Twenty-four percent of the respondents had no inventory of their collections; thirty percent had never inspected them for conservation needs. Most records of excavations conducted on U.S. Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management lands prior to 1975 and 1968, respectively, had been lost or destroyed.

Yet another example that is directly germane to this discussion is the National Park Service's oversight of the H.M.S. Fowey wreck site, mentioned previously. This wreck has been investigated several times since the early 1980s, yet, according to the National Park Service, no final report exists of any work conducted on Fowey. Further, as of January 2002, artifacts collected from this wreck during work conducted in 1993 and 2000 have yet to be accessioned, inventoried, or cataloged by the National Park Service, and no analysis of these artifacts has been done. In some isolated cases it would appear that the stewardship of our cultural resources - for the public good - is simply a facade.

Like underwater archaeologists, wreck divers also recover artifacts for the public good. Numerous recovered artifacts are presented in virtual museums on the Internet, displayed at public presentations, and documented in books. For example, several artifacts recovered from the wreck of the liner Andrea Doria, including the priceless frescoes completed by artist Guido Gambone, have made their way around the United States and Italy for public viewing. Had an in situ management regime been pursued for the Doria, these massive works of art, along with countless other unique artifacts would undoubtedly have been destroyed during the ongoing collapse of the wreck. As explorer John Chatterton puts it, artifacts, in this case, are actually recovered from oblivion."

The wreck diving community is responsible for the discovery, identification, and documentation of numerous wrecks on an annual basis. According to Sophia Exelby, U.K. Receiver of Wreck, "The vast majority of the wrecks which are designated as being of national historic interest under the Protection of Wrecks Act 1973, have been discovered by recreational divers." Due to the various constraints and economic issues that are presented in deep and/or remote shipwreck exploration, it is not always feasible to conduct an extensive non-invasive survey of an unidentified wreck site. Many times the identification of a particular shipwreck depends on the recovery of a unique artifact that possesses manufacturing data or other information that either identifies the shipwreck outright or facilitates further archival work. Should Draconian measures be implemented and artifact collection be prohibited, it will undoubtedly inhibit discovery.

Finally, there have been concerns within the diving community that the recovery of artifacts impairs the aesthetic appeal of a shipwreck. This article has already addressed the issues of shipwrecks resting in stable environments and has endorsed an in-situ management policy for those resources. However, for exposed shipwrecks, the aesthetic impacts issue really holds no merit. As pointed out, the integrity of coastal and even deep-water shipwrecks are largely at the mercy and whims of Mother Nature. The majority of these exposed shipwrecks visited by divers have collapsed and eroded over time. Many of the brass, ceramic, or glass artifacts that are recovered can be found under fractured bulkheads or buried under debris. Their removal does little to impact the overall aesthetics of the wreck.

Further, it should be noted that perhaps over 90 percent of all shipwreck diving activity in Florida (one of the top diving destinations in North America) is conducted primarily on artificial reefs. That is, most wreck dives in Florida are conducted on vessels that have been stripped down of equipment and nautical artifacts, in preparation for use in the marine environment. Instead of venturing out to one of the many natural shipwrecks that are broken down and collapsed across the seabed, but still possess many artifacts, divers opt to visit bare vessels with vacant interiors. Therefore, it is hard to seriously consider this aesthetic argument when evidence to the contrary so overwhelmingly contradicts it.

SEEKING COMMON GROUND

Shipwreck salvage, which technically would include artifact collection by wreck divers, in many cases is a perfectly legal activity that should not be vilified by others. It should be stressed that those who do not have the proper knowledge and dedication required to properly conserve and restore shipwreck material should not be encouraged to recover artifacts from shipwrecks. Once an object is removed from the water, it will deteriorate at a rapid pace. Artifact recovery is relatively easy in comparison to the numerous months or even years required to effectively conserve and restore an object. This information, however, is available to those that wish to educate themselves, and many wreck divers have expertly recovered and restored fascinating artifacts from countless vessels lost at sea. In the process, numerous unknown shipwrecks have been identified, and the final resting places of hundreds of shipwrecks have been documented. In some cases, history has even been rewritten.

The intent of this article is not simply to be critical of any one particular user group. Instead, perhaps individuals from the various sectors will realize that each group shares something in common and that there are more similarities than differences. Many wreck divers are keenly interested in history, not only in learning about our maritime past, but also in preserving it. This is one reason why many divers recover shipwreck artifacts, and spend vast amounts of time and money conserving, restoring, and displaying them. Society can and has benefited from the collection of artifacts outside of the archaeological community in some situations, just as it has also benefited from strict management and protection of certain cultural resources in others. If nothing else, it is hoped that people will come to understand that shipwreck artifact collection and cultural resource management are not necessarily "black and white" issues, and that there are many shades of gray in between.

Michael C. Barnette is the Founder and Director of the Association of Underwater Explorers, a coalition of divers dedicated to the research, exploration, documentation, and preservation of submerged cultural resources. Employed as a marine ecologist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), he recently published Shipwrecks of the Sunshine State: Florida's Submerged History, which offers an extensive and comprehensive cross-section of Florida shipwreck narratives.