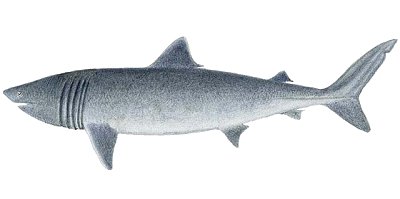

Basking Shark

Cetorhinus maximus

Size:

to 45 ft

Habitat:

open ocean

Notes:

harmless

The Basking Shark is second in size only to the Whale Shark, and much more likely to be spotted in our cool northern waters. Like the Whale Shark, the Basking Shark is a harmless plankton feeder. While the Whale Shark has a brown and cream checkerboard pattern on its back, the Basking Shark is more uniformly gray, making identification easy. It also differs in profile: while the Whale Shark has a broad square snout, the Basking Shark has a pointed conical snout, much like its cousin the Great White, for which it may be mistaken.

Basking Sharks are common off Massachusetts and northward, and not uncommon off New Jersey and Long Island, where they swim lazily at the surface ( hence the name ) and are probably responsible for most reports of monster Great Whites. A 20-foot Basking Shark would be of small-to-average size, while a 20 foot White Shark would be of unheard-of proportions.

As you can see, a Basking Shark really doesn't look or act much like a Great White, so all you South Jersey divers can stop scaring yourselves silly whenever you run across one. But then, what newspaper is going to print a story like "Divers Encounter Harmless Basking Shark"? I suppose a little embellishment is necessary to get your name in the news.