Tunas

by Bruce Freeman

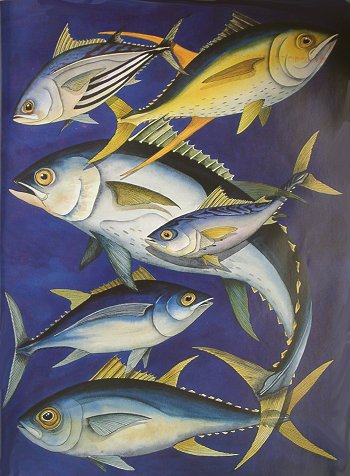

Six of the world's 13 tuna species occur off New Jersey each year. Among the most beautiful and powerful of sea creatures, the tops of their heads and their upper backs are either solid or wavy lines of dark, lustrous, metallic blue. Their sides are silver or silver-gray, often with silvery spots, bands, and iridescent hues of purple, pink and gold and silvery-white on the belly. Most young tunas have striking vertical bars along the body flanks, although these disappear with age. The beautiful coloration and patterns serve as camouflage.

Their streamlined bodies are the ultimate in hydrodynamic design. When tunas swim rapidly, all their fins - except two small vertical ones needed for stability and the small finlets used to reduce drag - fold into slots or grooves in the body so as not to interrupt the body's contour. Even their eyes are set flush in the head to form a smooth surface.

Tunas have either very small scales over much of their body or specially modified ones situated just behind the head and along the upper back. These, called corselet scales, are believed to reduce drag by increasing slightly the turbulence of the water flowing around the widest part of the body. The tuna's tail is curved in a crescent shape, providing maximum forward thrust, so it's not surprising that tunas are among the world's fastest swimmers.

Tunas frequent temperate and tropical seas, where the surface water temperature exceeds 64°F, and have developed a unique circulatory and respiratory system. The circulatory system - the heart and blood vessels - is designed to conserve heat during periods of inactivity and to dissipate heat as the activity level increases.

A high metabolic rate enables tunas to maintain a body temperature 10-20°F above that of the surrounding water. This may allow sugars in the muscles to break down faster, providing chemical energy for bursts of speed. An elevated stomach temperature speeds digestion, and the brain and eyes may also perform better at a higher body temperature.

Tunas take a larger proportion of dissolved oxygen from the water than do most other fish. The surface area of the gill filaments, the oxygen-gathering organ, approaches that of the respiratory surface area, found in the lungs of mammals of similar weight. The concentration of oxygen-transporting hemoglobin is as high in tunas as in humans.

Tunas swim constantly, holding their mouths open to force water past their gills. This also compensates for the lack of the swim bladder, the organ that makes fish buoyant. If they need to swim up or down in the water column, the pectoral fins, which act as hydrofoils, are extended away from the body.

Tunas have two types of muscle tissue: white, for short bursts of speech, and red, which functions in continuous swimming. In tunas, the mass of red muscle is rather large, enabling them to swim for long periods without fatigue. Their speed and stamina, coupled with their large size, make tunas among the world's most popular game fish. Also highly sought by commercial fishermen, they make up one of the most valuable fisheries in the world. The tuna harvest from the Atlantic Ocean accounts for about 20 percent of the worldwide catch.

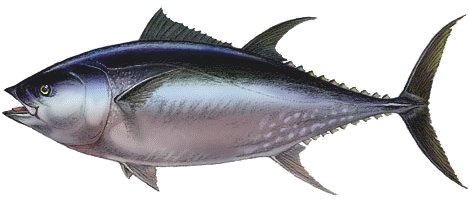

Historically, Bluefins Thunnus thynnus were the most abundant species of tuna occurring within 20 miles of the New Jersey coast. Today, regulations restrict the catch. Bluefins ranging from a few pounds to 14 feet and more than 1,000 pounds occur off New Jersey each summer and fall. Fish weighing up to 100 pounds are known as school tuna; those weighing between 100 and 300 pounds are designated mediums; those larger than 300 pounds are called giants. The maximum size is about 1,800 pounds. School bluefins first occur southeast of Cape May in late June or early July and work their way to off Sandy Hook by mid to late July. Giants occur mostly in the fall and are among the trophies most prized by anglers.

Yellowfin Thunnus albacares, bigeye, and albacore tuna occur close to our ports between June and October and can be found even further offshore, along the edge of the Gulf Stream, year-round. Yellowfins are by far the most abundant of the three. They usually occur within 30 miles of shore, but also are common up to 90 miles out. They are the major species taken by offshore anglers, who annually land between 5,000 and 20,000 yellowfins. In the recreational fishery, their average weight is 50 to 60 pounds, though fish as large as 6 feet and 290 pounds have been taken.

Albacore Thunnus allaluga occur in somewhat cooler ocean waters than do yellowfin, and usually are found from 50 miles out to the edge of the continental shelf ( 95 miles ) and beyond. in years where ocean water temperatures are cool, albacore tend to dominate the offshore catch. Those taken off New Jersey average 40 pounds, with some as large as 75 pounds and 50 inches.

Bigeyes Thunnus obesus favor oceanic waters more than 600 feet deep. They usually are taken along the edge of the continental shelf and at the heads of submarine canyons. Those taken off our coast average about 150 pounds, although some are as large as 365 pounds and 8 feet.

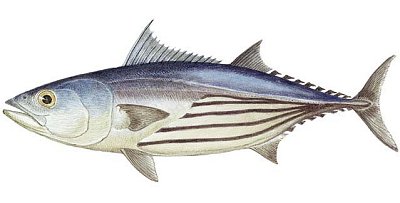

Skipjack tuna Euthynnus pelamis occur from 10 miles offshore and over the entire continental shelf in schools numbering from 10 to tens of thousands. Not usually targeted by anglers because of their small size, skipjacks have an average weight of 5 to 6 pounds; rarely do they exceed 15 pounds off New Jersey, although they do reach 75 lbs and 40 inches.

Little Tunny Euthynnus alletteratus ( a.k.a. Little Tuna ) occur along ocean beaches up to 30 or 40 miles offshore. They average 8 to 10 pounds but can be as big as 50 pounds and 40 inches. Because of their speed and strong fighting characteristics - and the fact that they occur close to shore - little tunny have become very popular with light tackle anglers, who find them challenging to land. Because of their dark flesh, however, they are not favored for eating and those that are caught are released.

Bruce Freeman is a research scientist with the

Division of Fish, Game and Wildlife's Bureau of Marine Fisheries.

This article first appeared in New Jersey Outdoors - Fall 1998