Oregon (2/2)

Chapter 30: Oregon

reprinted from Shipwrecks of New York by Gary Gentile

Courtesy of the National Maritime Museum

| Built: | 1883 |

| Previous names: | None |

| Gross tonnage: | 7,375 |

| Dimensions: | 501' x 54' x 38' |

| Type of vessel: | Passenger liner |

| Power: | Coal-fired steam |

| Builder: | John Elder & Company (Fairfield Yard), Glasgow Scotland |

| Owner: | Cunard Steamship Company |

| Port of registry: | Liverpool, England |

| Sunk: | March 14, 1886 |

| Cause of sinking: | Collision ( probably with schooner Charles H. Morse ) |

| Depth: | 130 feet |

The Oregon is without a doubt the most well-known and most frequently dived shipwreck covered in this volume, and is worthy of the broadest possible coverage in the greatest amount of detail. The Oregon is remembered not only by her unique place in history, as a first-class luxury liner which once held the record for the fastest transatlantic crossing, but by the wealth of memorable collector's items which have been, and continue to be, recovered from her rusted remains.

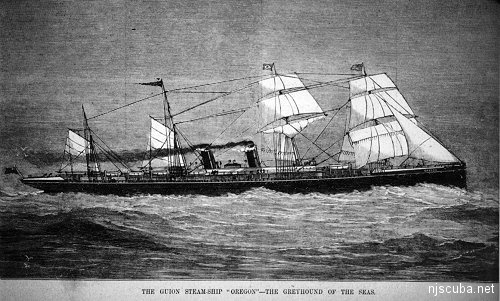

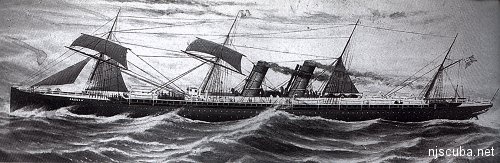

The Oregon was built for the Guion Line with the specific objective to construct the fastest liner in existence, faster even than her predecessors, the Arizona and the Alaska, the prototypes, also owned by Guion, on which the Oregon was patterned. Her hull was more streamlined both forward and aft so she could cleave the water more efficiently and leave less of a wake. Her triple-expansion reciprocating steam engine was slightly larger than those fitted into the Arizona and the Alaska. The high-pressure cylinder occupied the center position: it had a diameter of 70 inches and was flanked by two low-pressure cylinders each with a diameter of 104 inches. "The connecting rods are geared into cranks which balance each other and produce a smooth and equal motion. The piston stroke is six feet." the engine was capable of generating 13,000 horsepower, which is "equal to 191,517 tons lifted a foot high every minute."

Steam was fed to the engine from nine Fox patent double-ended boilers, each 16-3/4 feet long and 16-1/2 feet in diameter. Each boiler was heated by six furnaces, three at either end. The boilers were placed in three rows of three; in each row, the boilers nearly touched each other, with the outer two boilers coming in close proximity to the sides of the hull. The uptakes for the center row of boilers were split so that the uptakes for the forward end of the boilers fed into the forward stack, and the uptakes for the after end fed into the after stack.

"300 tons of coal a day must be brought to the fires, and the ashes removed; 2,500 tons of fuel must be stored and handled. The confined area of the vessel seems to forbid the employment of anything except manual labor in the work." Of coal-passers and stokers, there were many, but it was said that the engine could be operated by only two engineers.

The screw propeller was twenty-four feet in diameter; it pushed "The ship ahead with a power equal to that of twenty of the most powerful locomotives, " and at maximum revolutions could maintain a speed better than eighteen knots. The shaft connecting the propeller to the engine was not a single cast, but consisted of fifteen separate parts made of "crucible steel."

Two enormous in-line smokestacks dominated the Oregon's profile, looking all out of proportion to the size of the ship, but raked so that they imparted a sense of speed. As was typical of the day when passengers did not yet have complete faith in the reliability of steam engines, the Oregon also carried masts, sails. and rigging. The two masts forward of the stacks were square-rigged; the two masts abaft the stacks were fore-and-aft rigged. The masts were raked at the same angle as the stacks. It is unlikely that canvas was ever actually unfurled to aid the ship's propulsion, although staysails may have helped to maintain a heading in adverse wind conditions.

Although Lloyd's Register of Shipping lists the Oregon's length as 501 feet, by a different system of measurement the Oregon is sometimes listed as having a length of 520 feet, but this latter figure must be taken from the point of the stem to the counter. On the original builder's plans the "length between perpendiculars" and the "length on the load waterline" are both given as 500 feet, and the "length overall" is given as 518 feet.

The Oregon was "built of iron, with nine transverse watertight bulkheads, five iron decks, and a strong turtle-back deck forward and aft as a protection from the heavy seas. She was fitted to accommodate 340 saloon, 92 second-class, and 1,000 steerage passengers." However, in order to achieve accommodations for that number in steerage, the lower deck had to be stripped of partitions and appurtenances.

She did not enjoy the safety advantages of double-hull construction, which was known at the time but which was in general disfavor due to the added construction costs and to the reduction in speed caused by the increased weight of the hull. Scientific American noted that "probably no finer specimen of marine architecture than the Oregon has yet been produced. She was unsurpassed in strength and speed, and supplied with many requisites for safety, but lacking in flotation power and in devices suited for the temporary stoppage of leaks. She had no special means for preventing access of water to the furnaces."

Passengers traveling "saloon" or "cabin" were equivalent to what is called "first-class" today. "Second class" passengers were sometimes referred to as "intermediates." there were no more steerage passengers ( those who traveled in a giant bunkroom in the ship's after portion, where the noise and vibration from the propulsion machinery was the greatest, and who on some vessels had to supply their own food ); they had been upgraded to "third class, " and given berthing space below decks in small rooms which were cramped and without adornment; they received food and services commensurate with the ticket price. You get what you pay for.

The Oregon was elegantly ornamented. "The grand saloon, capable of dining the whole of the 340 cabin passengers, was placed in the fore-part of the vessel and was laid with a parquetry floor. The ceiling decorations were almost exclusively confined to white and gold. The panels were of polished satinwood, the pilasters of walnut, with gilt capitals. The saloon measured 65 by 54 feet, and was 9 feet in height in the lowest part. A central cupola of handsome design, 25 feet long and 15 feet wide, rose to a height of 20 feet, and gave abundant light and ventilation."

The saloon was forward of the engine. "The staterooms are large and well lighted and ventilated. Every facility for comfort is provided in the cabin. The ladies' drawing room is furnished in a costly manner and is on the promenade deck. The latter extends nearly the entire length of the vessel. The woodwork of the ladies' drawing-room, the Captain's cabin, and the principal entrance to the saloons came from the State of Oregon. On the upper deck near the entrance of the grand saloon is the smoking room, which is paneled in Spanish mahogany and has a mosaic floor. Incandescent electric lamps, supplied by the Edison Company, are used in lighting the vessel." At the time, the light bulb was a recent and much-touted invention which was in the beginning stages of replacing candles and gas lanterns.

The Oregon was built and fitted out at the Fairfield Yard of John Elder & Company, outside Glasgow, Scotland. The amount charged to Guion for construction was $1,250,000.

When the Oregon was launched with great fanfare, on June 21, 1883. she was advertised as the largest merchant steamer afloat. This statement was true only by default, or possibly by semantics, and was carefully worded so that it represented a technicality of language rather than the reality of marine construction. Without a doubt, at that time the largest steamer ever afloat was the Great Eastern, whose maiden voyage occurred nearly a quarter of a century earlier, in 1860. The Great Eastern stretched 693 feet from stem to stern and grossed 22,500 tons. Initially, she plied the transatlantic lanes carrying passengers and freight, but then she was chartered for the task of laying submerged telegraph cables around the world, at which point she was no longer occupied in the merchant trade. After a long and tumultuous career, by the time the Oregon was done building. The Great Eastern was laid up and no longer in active service.

The Oregon departed Liverpool on October 7, 1883, bound for New York. She was full of promise for her passengers and burdened with expectations from her owners and investors. She delivered on both responsibilities, but not with immediacy of action. Unlike other -- sometimes more tragic --maiden voyages, the Oregon was not pushed to the limits in order to achieve fame straight off the building blocks. Captain James Price, master of the Oregon and commodore of the Guion fleet, coddled his charge like a newborn child. He ran the ship, and let the engineers run the engine. As a consequence, the engineers reduced speed several times because the bearings overheated. Nevertheless, the Oregon completed the westward passage in the respectable time of seven days, eight hours, and thirty-three minutes. The best day's run occurred on Captain Price's sixty-first birthday when the ship made 456 miles in twenty-four hours.

Her shiny black hull, embellished with a broad streak of red paint at the waterline, like a modem-day racing stripe, cleaved the water effortlessly. Her deck-houses and joiner-work were white as snow and the brass-work which covered rails and portholes shone like burnished gold in the rays of the sun." If a ship, being an inanimate object, cannot be proud, certainly her captain, officers, and crew could display such emotion as pride. Many notables among the passengers, today forgotten, commented to reporters on the ship's grace and elegance.

The Oregon's arrival in New York was not greeted with any kind of fanfare. She docked at Quarantine, a small island in the harbor, and waited there for several hours while health inspectors conducted their examination. The inspection was routine, and when the ship was cleared the Oregon moved on to the Guion pier at the foot of King Street. One reporter was so impressed by her size and magnificence that he described her as "a Broadway block moving through the water."

Not until her third voyage was the Oregon put to the test. By this time her engineers had full confidence in the performance of the machinery. She left Queenstown at noon on April 13, 1884. She ran into fog on the Newfoundland Banks, then encountered "considerable ice, " which she avoided by taking a more southerly route than usual. She passed Sandy Hook on the afternoon of April 19, completing the passage ignominiously by running aground on a shoal in the Gedney Channel. However, she floated off with the rising tide without damage. The corrected time for the passage was six days, ten hours, and ten minutes, the quickest passage on record, and beating by more than eight hours the fastest crossing of the Alaska in either direction. So fast was the passage that she arrived in New York a day before the shipping line agents expected her.

Thus the Oregon achieved fame as a winner of the Blue Riband: a trophy awarded to the liner with the fastest transatlantic crossing, and held by that liner until usurped by another. This was the finest moment for both the Oregon and the Guion Line. But the moment was short-lived.

Despite the Oregon's success, the Guion Line was experiencing financial difficulties. Her vessels were not generating enough revenue to enable the company to maintain the payment schedule to the builder, to whom the ship was heavily mortgaged. Guion was forced to default on the loan, so the Oregon was taken back by John Elder & Company, to whom the ship became more of a liability than an asset: a white elephant which generated no revenues. Fortuitously, the Cunard Steamship Company was at that very moment contracting with Elder to build a pair of fast liners to compete with Guion's fleet. As the two ships were still in the design phase of construction, delivery of the completed vessels was a couple of years down the line. Elder offered to sell the Oregon to Cunard as an interim liner, and Cunard wasted no time in accepting the offer. Title to the liner was taken by Cunard on May 21, 1884.

No sooner had this occurred than the National Line put into service the latest addition to its fleet, the America, built by J & G Thomson of Clydebank, Scotland. On her maiden voyage, she took the Blue Riband away from the Oregon, not on the westward passage, which commenced on May 28, but on the eastward. Thus the trophy was passed to the National Line.

A crucial if peripheral incident occurred on the Oregon in June. Her electrical plant broke down while she was in New York, and her departure had to be delayed until the dynamo could be repaired. A call placed to the Edison Electric Light Company produced no immediate result. Finally, a very frustrated shipping manager called Edison direct and demanded that he send an electrical engineer forthwith, with emphasis on the forthwith. The ship was losing money every day she stayed in port. Edison agreed and hung up the phone. But it was an exceptionally busy day and all his engineers were out handling emergencies.

Who should walk into Edison's office at that very moment but a young Serbian immigrant who had arrived in America only the day before, aboard the Saturnia. He handed Edison a letter of introduction from British engineer Charles Batchelor, and, with excellent command of the English language, asked for a job. The reference seemed authentic, so Edison asked him if he could fix a ship's lighting plant. The Serbian proclaimed boldly that he could, so Edison hired him on the spot and brashly dispatched the man with some instruments and told him to fix the Oregon's electrical system. With the aid of the ship's crew, the Serbian worked straight through the night, tracing short circuits and mending broken wires in the dynamo, until at dawn there was light.

That young Serbian engineer was Nikola Tesla. He worked for Edison for several more months, but the company was not big enough for two men of such vastly different talents, especially as their convictions about the generation of electricity differed so radically. Thomas Alva Edison, the man who was known as the Wizard of Menlo Park, was a staunch believer in direct current because he thought it was crucial to the sale of incandescent light bulbs, which he invented and on which he had the patent. Nikola Tesla was a genius in his own right who saw the advantages of alternating current, and who could not abide Edison's repudiation of a system which had so many obvious advantages. The two parted ways, and for years fought as bitter rivals over which type of electricity should prevail. In this Edison failed, and Tesla went on to form his own company, which designed. built, and installed alternating current generating systems throughout the land. Today, direct current is limited to only a few applications in which a one-way flow of electrons is superior to a reversal of flow.

The Oregon transferred her affections from Guion to Cunard without reserve. Her engineers tweaked her engine for every bit of power, and her machinery ran more smoothly with each succeeding passage. Soon she bested her own time. In August she wrested the fastest passage back from the America and claimed the Blue Riband for her new owners: first for the westward passage, then for the eastward. There was no faster liner in the world than the Oregon. By the end of the year, she had trimmed the westward passage to six days, nine hours, twenty-two minutes, and the eastward passage to six days. six hours, fifty-two minutes. Cunard was justifiably proud of her new acquisition.

In March 1885, due to the escalation of hostilities in Afghanistan between England and Russia ( the Second Anglo-Afghan War ) the British government chartered some of the fastest Atlantic greyhounds to support the fleet. The Oregon was fitted out as a cruiser but served primarily as a dispatch vessel. The political tension soon diminished, with the result that all the liners drafted for military service were returned to their owners except the Oregon. In July, she took part in naval maneuvers in Bantry Bay in order to "give the Navy a clear idea of just how useful these ships could be in their naval role."

Bigger and faster and more luxurious liners were on the ways, and while the Oregon continued to provide good reliable service for peace and war, it was only a matter of time before her speed record was broken. In August. while she was off fighting the war, her place was eclipsed by a newer Cunard liner, the "super hotel" Etruria, which took the Blue Riband for both passages on a single voyage. ( However, the Etruria is also credited with what is perhaps the longest-running time on record. During one voyage her propeller sheared off in mid-ocean, taking the rudder with it. The ship wallowed for days before a passing steamer took her in tow. She was twenty-eight days making port. )

At summer's end, the Admiralty returned the Oregon to Cunard, which quickly refitted the ship for passenger service. By November 1885 she was back on her familiar run between Liverpool and New York.

And so we come to 1886, and to the end of the Oregon's brief but prestigious career. Now in command was Captain Philip Cottier, a veteran master of the transatlantic liner service though only forty-five years old. On Saturday morning, March 6, final preparations for departure were made in Liverpool. Passengers queued up on the wharf and waited their turn to climb up the angled gangplank. Of the nearly 650 passengers, 186 were traveling first class, 66 were going second class, and the third class compartment contained either 389 or 395 (accounts differ). The number of officers and crew totaled 205, and all were busy performing their assigned duties and functions.

To add to the hustle and bustle, hordes of longshoremen filled the cargo nets with 1,835 tons of freight, which had to be hoisted, swung aboard, and lowered through the hatches into the holds. The various commodities were consigned to some 850 firms and individuals in New York City and were valued at $700,000. This cargo consisted of silk, cloth, dry goods, books, dyestuffs, hardware, machinery, earthenware, fruit, whiskey, steel, tin plate, rubber, and building materials.

In addition to bulk cargo packed in crates and stowed below were several expensive consignments of diamonds destined for such famous jewel importers as Smith & Knapp, Peterson & Royce, W.S. Hedges. and A.H. Smith & Company. These were kept in the purser's safe.

Also being loaded were 598 bags of mail. The Oregon was designated by the British government as a Royal Mail Ship. This means that she was charged with the responsibility of carrying official documents and ordinary mail. While this sounds like a royal privilege, it is not, as most liners operating under the British flag were designated as Royal Mail Ships. The practice was as common as today's commercial airliners carrying airmail letters and about as important.

Among these bags of mail were two official dispatch bags, 113 closed bags containing letter mail for the U.S. and Canada, 2,400 registered letters, and 470 bags of newspaper mail. The letter mail originated from countries such as France, Italy, Sweden, and Russia. Money order posts came from England, Cape Town, Germany, Switzerland, Denmark, Belgium. and Portugal. Also packed in mail bags were more than $1,000,000 in negotiable coupons and greenbacks, and some $2,000,000 worth of stocks, bonds, and other securities ( including 10,000 shares of Reading Railroad stock worth $500,000 ). None of this was out of the ordinary; it was regular commerce.

The Oregon departed Liverpool the same as she had many times in the past. It was a typical Saturday morning, the air was clear but cool. The weather continued fair most of the way across the Atlantic, except for a high swell and brisk southeast winds encountered off the banks of Newfoundland, which soon passed. No untoward events occurred during the passage to disturb the routine of the crew or to affect the activities of the passengers. If anything, the crossing was subdued by boredom.

Long Island hove into view during the night of March 14. As usual, the Oregon passed along the south shore at a distance of about five miles. A fresh wind picked up from the west, but not hard enough to appreciably stir the surface of the sea, which remained flat and calm according to some witnesses, and had a slight chop according to others. Captain Cottier retired, knowing that the ship was in the good hands of his Chief Officer, William George Matthews. The Oregon steamed west at a speed of better than eighteen knots. With anticipated arrival only hours away, the passengers' baggage was removed from the hold and stowed on deck in preparation for unloading immediately upon docking.

By 4:30 in the morning, the Oregon was halfway between Shinnecock and Fire Island. Stated Chief Officer Matthews: "The fourth officer was on the bridge with me. He stood on the port side, and I stood on the starboard side. There were three men on lookout duty, two on the turtleback, and one on the forepart of the promenade deck. The latter was able to keep a lookout and pass the word along from the other men. The night was tolerably clear, but the day was not broken when the collision occurred. The first sign of the proximity of another vessel to our own was the sudden appearance of a bright light off the port bow. It appeared to me to be a light just held up for a time, for it disappeared instantly. It was just like a flash of light. I thought that it must be on a pilot boat with her masthead light out. Pilot boats do not carry side lights. Knowing that the Captain was not going to take on a pilot until we reached the bar, I had the helm put hard aport to bring the light more broad on the bow."

Today's readers need to understand that in the Oregon's time the convention for steering directions was opposite to what it is now. The steering wheel was linked in reverse to the steering gear, so when the top spoke of the helm was turned to the left ( counterclockwise ) the rudder--and consequently, the direction of the vessel--turned to the right.

When asked how high the light was held, Matthews replied, "I assumed that it was in the hands of a man standing on the deck. I saw no other lights at all; there were no colored lights. My first impression was that a vessel was there without any lights and that somebody on her deck, suddenly perceiving the approach of the steamer, had grabbed the first light that came to hand and hastily held it up ... but the steamship did not have time to change her course before the collision occurred. I saw no sails nor the outline of the schooner until she was on the point of striking us. When I gave the order to change the ship's course I had not the slightest idea there was going to be a collision. I could not tell from the light whether the unknown vessel was moving or standing still, or in what direction she was headed. There were no regulation lights in sight ... I could not see her name or anybody on her. I could not even discern how many masts she had. I had no time to think between my giving the order to put the helm hard aport and the collision. The schooner struck the Oregon a few feet forward of the bridge upon which I stood. The blow did not careen the steamship over. It was a sort of glancing blow.

"The instant I heard the crash I signaled the engineer to stop the engines, which was done at once. Then I turned to look for the schooner. The Oregon was obeying her helm and swinging around. I looked all around the horizon but could see nothing of the schooner. I heard no noise, no shouts, or talking among the schooner's men. No words were exchanged at any time between the two boats."

Mrs. W.H. Hurst saw the collision from a different perspective: "I had passed a sleepless night and was looking out through the deadlight into the almost impenetrable darkness. I could see the twinkling of a few stars away out where sea and sky seemed to meet. My husband awoke just then, and I spoke to him without turning my head. Suddenly the stars were shut out from view by some passing object. Then a brilliant red light shot by my cabin window, and I was calling my husband's attention to it when there was a terrible crash at the vessel's side, close to our stateroom. It was so severe as to nearly throw me off my feet, and it made the vessel shiver and tremble in a frightfully suggestive manner. My husband and I hurriedly dressed, for we knew that the steamer had been struck, and we supposed by another steamer ... While we were dressing there was a second crash, and then a grinding noise and the crushing of timbers. This last and most frightful of sounds was followed by the crash of a mass of falling timber ... There was only one stateroom between ours and the dining saloon, and it was immediately under this that the great holes had been torn in the Oregon's side. I could hear the water rushing into the hull of the vessel, or imagined I could, and was terribly frightened, for death seemed to me to be very, very near. The dining room was comparatively empty when we reached it and passed through it and up on deck, for we were among the first to get out."

A Mr. L.C. Hopkins was also up and about at the time of the collision. "I had been sick all through the voyage and could not sleep. I was taking some toast and tea when I heard a crash and felt a shock that shook the Oregon from end to end. A frightful crash and clatter, as of the falling of an immense mass of iron plates, came from the port side. A moment later there was a second crash and shock. A third, but lighter, shock followed... . I went to my stateroom and called my wife out. Within eight minutes after the first crash and shock an officer of the Oregon came from the deck and cried out: 'Call everybody and order them on deck.' the women and children had begun to leave their rooms and, half-clad, to crowd the passageways. They were urged out of them, and as fast as the passageways were cleared the iron doors were closed so as to make several compartments watertight. The passengers were hurried to the deck, where they had to stand close together for warmth. Most of them were ill-clad. Some of the children were bare-legged and barefooted. The mercury was at 32 degrees, and ice formed on the deck, but no one grumbled or screamed. The crew began to get the boats ready, and, to the praise of the company, they worked in a way that showed excellent discipline."

The rattle of telegraph chains alerted Captain Cottier that something was amiss. He raced up to the wheelhouse, where Matthews told him the situation, then relieved the Chief Officer and assumed command. This was a matter of procedure, not an indictment of performance. The forward momentum and the hard-turned rudder gradually brought the Oregon around until she completed half a circle and was heading back the way she had come. The reversed engine gradually brought the liner to a halt, after which the vessel drifted slowly seaward with the tide. Captain Cottier ordered an inspection of the damage. The news was not good. Two terrible gashes were torn in the side of the hull in No. 3 compartment, near the coal bunkers.

Captain Cottier at first thought that the Oregon would survive the ordeal, as only one compartment appeared to have been breached. But it soon developed that the point of impact was right on the edge of a watertight bulkhead, with the result that two adjacent compartments were flooding, and much faster than the pumps could eject the overflow. The situation did not look good.

Two men were lowered down the outside of the hull in boatswain's chairs: Second Officer Peter Hood and the ship's carpenter, John Huston. Mattresses and pillows were handed down to them, and they stuffed these into the jagged openings. But the mattresses and pillows were sucked into the ship by the fast flow of water which they were attempting to stem.

Next, a huge sailcloth or collision mat was worked down over the crash site. "An attempt was made to fasten these over the holes below the waterline by the use of chains and toggles. Huston, divesting himself of all superfluous clothing, dove into the water and tried to make fast the chains. Three times he went down under the icy water in a vain attempt to find a method of stopping the inflow of the water. The efforts were fruitless, and Huston, much against his wishes, was deterred by Officer Hood from making a fourth attempt."

The collision mat was eventually secured by working ropes over the bow and under the hull, then bringing them up taut on the opposite side of the ship. The job was accomplished and the flow of water was somewhat diminished. By this time the ship was quite a bit down by the head and listing perceptibly to port.

From all accounts, there does not appear to have occurred an outbreak of total pandemonium, but there was at the very least a great deal of activity and concern among the passengers and crew, and, understandably, a certain amount of confusion. One unidentified passenger claimed that "although he slept on the side where the break was, he did not awake until called by a steward." Another passenger, Captain T.R. Huddleston, was either exaggerating or pulling a reporter's leg when he said that "he awoke three hours after the accident, blacked his boots, dressed himself carefully, and came out to breakfast, and only then heard of the collision." Perhaps, not hearing the thrumming of the engine or the vibration which ran incessantly throughout the metal hull, he thought the ship was docked at Quarantine.

Guns and rockets were fired to attract the attention of vessels in the vicinity. Hopkins noted, "They had not been in use long when a big steamship appeared. She was bound out, but she passed on, paying no heed to our signals." Hopkins also noted that in the light of dawn "we had a chance to see what damage had been done to the Oregon. There were three holes on her port side. One was above the water and was 12 by 9 feet. The others were smaller, but one of them was below the waterline, and the sea was pouring into the hold." Another passenger thought the hole was large enough "that a horse and wagon could easily have been driven through it."

Worse than that, the sea surged through open hatchways whose watertight doors could not be tightly closed because the hinges were rusted or because the seals were choked with coal dust, or because the bulkhead had been twisted in the collision. This permitted flooding of the boiler room, and soon the fires were damped by the rising tide, leaving the Oregon without means of propulsion or electric power to operate the pumps. Drowning the burning coal also created "a tremendous cloud of steam. so dense and thick that the firemen in the fire room dropped their shovels and rushed to the deck, where all the passengers had been summoned, many clad in their sleeping garments."

About two hours after the collision. Captain Cottier was forced to admit the strong possibility that the Oregon might sink, so he ordered the lifeboats prepared for launching. it goes perhaps without saying that the Oregon did not carry enough lifeboats to save the entire ship's complement. No vessel at the time did. In fact, even though the Oregon had on board only half the number of passengers she could have carried, there was space on the lifeboats for only half of them. This situation has existed since merchant shipping began. and posed the same problems as it always has: some people must be left behind to go down with the ship. Who would they be?

Chief Officer Matthews stated for the record, 1 did not see any breaches of discipline on the part of the crew. There was no insubordination that I know of."

Mrs. Hurst again observed events from a different perspective. "The scene on deck was something awful. The people from the steerage were on deck, crying, screaming, and praying. It was a most awful combination of noises, and no one who heard it could by any possibility ever forget it. But above it sounded for a few minutes after I got on deck the curses and horrible oaths of the begrimed and half-attired firemen and stokers. They seemed to have mutinied, and the officers had no control over them. They were scattered all over the deck, and myself and other ladies and some children were so roughly pushed about that several of us were thrown violently to the deck. Finally, the officers were reinforced by a number of the gentlemen cabin passengers and order was in some measure restored among those rough men. It took force to do this, though, and the minor officers had to use staves and belaying pins and fairly club the men to keep them from capturing the lifeboats, our only hope of salvation. As it was, one boat, the first away, was filled with them."

A New York Times reporter interviewed Captain Cottier on the matter. "in explanation of the story that some of the Oregon 's stokers and firemen fought for the possession of two or three of the small boats immediately after the collision, Capt. Cottier stated that the only firemen who went near the small boats while they were being lowered were the men who were ordered by him to guard those boats. It is conceded that some of the steerage passengers rushed for the boats as soon as they found that the vessel was sinking, but they were driven hack by the mates and crew."

As counterpoint, another passenger begged to differ with Captain Cottier's sanitized account of the orderly abandonment of the ship. This anonymous Englishman was quoted as saying, "A more cowardly set of rascals than some of the crew of the Oregon were never got together outside of a jail. A party of them - firemen, I think - took possession of a lifeboat and were preparing to get away without taking anybody else in her when a brave sailor ran at them with a big stick and belabored them soundly. But he didn't drive them out of the boat. They lay in its bottom and yelled for mercy. Then some passengers got into the boat. If I hadn't lost my purse I'd like to give that seaman something handsome."

Mr. F. Frost was even more graphic and vitriolic: "Those rascally firemen deserved drowning. When 1 approached the boat they had taken they threatened me with belaying pins. As I did not want my head battered I gave them plenty of room."

A passenger, Mr. Sturges. recounted his role in commandeering the boat away from the firemen. I had not used a profane word since the first night of the Chicago fire until this morning. I cursed frightfully when I saw a party of firemen going away from the ship with a boat not half-filled. I called to them to come back. They would not return. Drawing my revolver and picking out the fellow who seemed to be their leader, I said, 'If you don't come back I will kill you.' they returned and we put 16 passengers into the boat. I believe I would have been justified in killing some of the rascals."

By comparison, Cunard's official press release was as innocuous as it was ingenuous: "With but few exceptions all behaved admirably, and with scarcely any trouble order was quickly restored. The partly dressed passengers were ordered to put on their clothing, and coffee was served to all."

It was estimated that not more than 400 people had been able to abandon ship in the ten lifeboats and three emergency rafts, crowded though they were, that the Oregon carried. That left upwards of 450 people awaiting their doom on the foundering liner. Even if they all managed to stay afloat when the ship went down, by wearing life belts or clutching life rings, it is unlikely that many could have long survived immersion in the frigid water before dying from hypothermia, or drowning.

What to wondrous eyes should then appear but two glorious sails billowing brightly in the west wind. It was the two-masted pilot boat number 11, better known as the Phantom, answering the Oregon's rocket's red glare. it was a small boat, but it had deck space available for scores, perhaps hundreds, of desperate people. The time was 8:30, four hours after the collision. The heavily laden lifeboats had all remained in the vicinity of the wreck. Now they rowed for the Phantom with all abandon and quickly discharged their human cargo so they could return to the drifting steamship and take off another boatload of survivors.

About an hour later, while the transfer of people was being effected, another ship, this one a schooner, approached the scene of the disaster. The Fannie A. Gorham was bound from Jacksonville to Boston with a cargo of coal. Captain Cottier waved her down and asked her captain to take the women and children from the overcrowded lifeboats so the boats could return to the ship for another load.

Now occurred one of the most absurd statements ever uttered, so ludicrous that it cannot be believed, and which is, in any case, more apocryphal than true, and probably a figment of the imagination of a reporter short on copy. As if it were a valid excuse for refusing to take on survivors, Captain Mahoney, master of the Fannie A. Gorham, declared, I don't have enough provisions."

To which Captain Cottier supposedly replied, "I'm not asking for provisions, I'm asking for transportation."

Fortunately, the seas were calm. Hundreds of people clambered from the lifeboats to the two sailing vessels and accomplished the task without a single injury and only little more than a dampened stocking. "Huston again distinguished himself by saving the lives of three passengers. He seemed ubiquitous while passengers were being assisted from the vessel into the boats. Several of these in their hurry to get into the boats fell into the water. Among these were the little son and daughter of an emigrant named Andrew McNab. A fat woman and a baby fell into the water at the same time, but these two were easily pulled into the boat. The McNab boy and girl were earned some distance from the boat.

Huston saw their danger, and, throwing off his coat, with which he was trying to drive off the oil from his previous experience in the water, sprang overboard. It was the work of only an instant, with his strong, sure stroke, to reach the children, and both were brought back to the boat in safety. Subsequently, Huston drew into the boat an elderly man who had fallen from the ladder into the water, while trying to get into the boat."

Meanwhile, the lifeboats rowed back and forth between the Oregon and the two rescue craft. One lifeboat made as many as five trips, each one full to the gunwales with male passengers and crew who had been left behind, It took hours, but at least now there was space for everyone aboard the rescue craft, small as they were. ( The Fannie A. Gorham grossed 324 tons, the Phantom less. But, as they say, any port in a storm. )

In the time-honored tradition of the sea, Captain Cottier was the last man to leave his ship. By that time "her deck was so low in the water that he was able to step from the rail directly into one of the small boats." Now every soul was accounted for, the boats were so crammed with people that it was nearly impossible to maneuver them. So Captain Cottier dispatched Third Officer Taylor in one of the lifeboats to head for land and telegraph for help. Obediently, Taylor and his crew rowed north.

Yet another vessel hove into view, at 10:30. This was the North German Lloyd passenger liner Fulda, also bound for New York. By now the sea around the Oregon was filled with lifeboats, rafts, and rescue vessels, on which were packed some 900 people: a sight which Captain Ringk, master of the Fulda, undoubtedly had never seen before. The Fulda stopped within half a mile of the Oregon and immediately offered assistance. Then began the laborious process of transferring all the people previously transferred to the Phantom and the Fannie A. Gorham to the more commodious German liner. This also took hours.

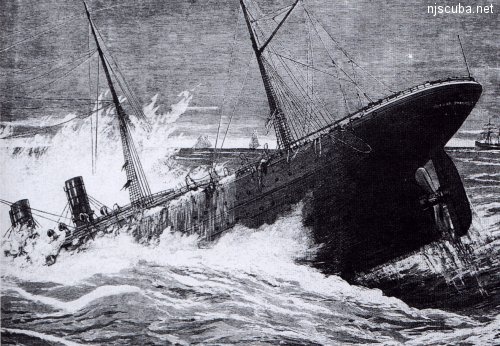

By 12:30 it was all over but the short hop to New York. After the last remaining passengers and crew from the Oregon had been transferred to the Fulda, the Cunard liner made her last bow. Mrs. Hurst: "The last I saw of the Oregon was from the deck of the Fulda, when she plunged bow first down to the bottom, her great propeller screw being the last thing we saw of her."

Another passenger's description was much more graphic. "While the disappearance of the beautiful steamer we had learned to love was in one respect an awful sight, it was at the same time one of the most picturesque things I ever saw. She had listed well over to port before the last boatload, with Capt. Cottier, surgeon McMaster, and the ship's carpenter, left her. She lay there seemingly in a struggle for life against the waters striving to engulf her. Five minutes before she sank the great vessel rocked backward and forward and rolled from side to side, a great helpless mass. Then, as her bow dipped, the great waves rolled over her, and the slender foremast gave way and swayed to one side. Then the prow rose for the last time, it stood well up in the air for an instant, and then, with a sort of spring from her keel as if preparing for a dive, the bow cut its way down into the waves she could no longer ride. There was a swirl of waters. Her dive was continued and the heavy stern swung well up so that we could almost see her keel.

Down she went head first, and the blades of the great propeller were thrown high and clear of the water. They, too, went down in the great gulf and the water boiled and bubbled and gurgled and lashed itself into a great mass of foam. We had seen the last of the Oregon."

Captain Ringk's observation was reserved: "When I first came up with her she was down at the head. Gradually she sank lower and lower, and all at once her head plunged out of sight under the sea and her stem came up like a teeter-totter. The stern rose so high in the air that you could see her screw-wheel. She remained in that duck-like position for a while, and then by degrees again she settled at the stem and went down as gracefully as though gliding off the cradles at a launch. It was all over in a minute or two, although as we all looked at the lovely creature in her helpless condition it seemed like a much longer time."

The Oregon had remained afloat for eight hours after the collision, time enough to conduct one of the most monumental rescue operations in the history of steamship passenger service, and without a single fatality. This enabled Cunard to continue advertising the fact that the company had never lost a life at sea. One passenger later quipped, perhaps in the euphoria of being alive, that "three dogs - a tether, a bull, and a skye - were saved." To which another chimed in, "But a Chicago man lost two magpies." Or perhaps they just flew the coop.

The Phantom and the Fannie A. Gorham were discharged from their duties and proceeded on their way. The Fulda continued on toward New York, her decks swelled with the addition of some 900 men, women, and children. Also on board were 69 sacks of mail which had been taken off the Oregon, and the entire consignment of diamonds which the astute purser, Robert Thorpe, had thoughtfully removed from the safe and stuffed in his pockets.

By this time news of some sort of casualty had reached Cunard's offices. The alert keeper of the Fire Island Life-Saving Station had noticed through his spyglass the great liner adrift, and thought he recognized her as the Oregon. He sent a telegram to Cunard noting his observations. Vernon Brown, agent of the Cunard Line, took immediate affirmative action without knowing exactly what the difficulty was. He chartered two tugs and himself boarded Cunard's Aurania, whose departure had been delayed by fog in the harbor, and all three vessels set out for Fire Island. ( Remember that this was before wireless telegraphy and ship-to-shore radio. ) Brown was working under the assumption that, since the Oregon had not arrived at her pier as scheduled, she must have been disabled. He issued orders to the Aurania 's captain to tow the Oregon to New York with the help of the tugs, then disembarked onto another tug and went back to his office where he could keep apprised of developments and be able to execute the duties of his position.

Later that afternoon Cunard received another telegram from the Life Saving Service, this one from the Forge River Station. According to the Service's annual report, the lifesavers launched a boat through the surf and "pulled out half a mile from the shore to a small boat containing a party of men who were making signals for help. It proved to be a yawl with a pilot, and the third officer, and three sailors belonging to the British steamship Oregon. A heavy sea was breaking on the outer bar with a dangerous surf running inside, and the third officer was the only one who would take the risk of landing with the life-saving crew. After waiting some time for a smooth chance a dash was made for the beach which was reached in safety. The yawl put out to sea again and was picked up by a passing steamer."

Third Officer Taylor gave a brief account of the accident and the fate of the passengers and crew and pleaded for rescue craft. He did not know about the arrival of the Fulda, and by that time the Oregon had drifted out of sight from shore. Brown must have gone mad with the paucity of details. He sent a telegram to the Forge River Station for more information, but by that time ( more than an hour later ) Taylor had gone. Remember that telegrams were not instantaneous like phone calls. A written telegram had to be hand-carried to a telegraph station, where it was transmitted by wire to another station, which then typed out the reply and sent the telegram by messenger to the addressee. The reply was just as long in coming.

That evening, after Taylor's terse telegram. The Fulda reached the outer bar of New York harbor and was forced to wait till midnight for the tide to change. She dropped anchor near the Sandy Hook lightship. A life-saving crew from the Sandy Hook Station boarded the liner and learned about the Oregon's demise. They returned to the station and, at 9:40 that night, sent a telegram to Brown at Cunard which contained only slightly more news than he already had: that the Oregon had definitely sunk and that the Fulda was bringing in the survivors. By this time word about the casualty had reached the media. Responding to a hot tip, three enterprising reporters from the New York Times chartered a tug to transport them to the Fulda. This was not technically permissible because the ship had not cleared Quarantine. They did it anyway, and thereby scooped all the other dailies and carried particulars of the event a full day before any of their competitors. Afterward, the New York Times deservedly tooted its own horn by printing an account of how the story was obtained.

The tug Ocean King bypassed Quarantine entirely and headed right out of the harbor. "The tug's whistle sounded in a most important and businesslike manner. There was a strong clash of Health Officer in the toots and an air of ease and authority about everyone on board the little vessel as she approached the big ocean steamer." When Captain Sam, master of the tug, shouted, "Make fast that line aboard the Fulda." his voice was imperious enough to carry conviction. No sooner was a line made fast than a rope ladder was tossed from the tug to the high rail of the liner. The reporters scrambled up the ladder as it swayed sickeningly back and forth, and gained the deck where "The extremely courteous officers tipped their caps to the reporters, who were amused, though rather mortified, to discover they were mistaken for Health Officer Smith and his assistants. Being in a hurry, however, they decided to defer explanations. as they had been informed by Health Officer Smith that under no circumstances would they be allowed to hoard the Fulda, though he had no objections, he said, to their holding a conversation with her officers or passengers from a distance."

The reporters quickly got away from the Fulda 's officers, who were deceived about the purpose of the aggressive borders, and lost themselves among the throngs of passengers in order to conduct interviews. They found Captain Cottier in a cabin so crowded that "its occupants were packed like figs in a box." While they were getting their stories, Captain Ringk learned the truth of their identity: he had more steam up than his ship. He ordered the tug's line cast off, then got the Fulda under way.

The reporters wrote their stories, but when they returned to the place where they had come aboard they found the Ocean King some distance away. They shouted for Captain Sam to take them off. As the tug closed on the liner, Captain Ringk rushed up to the reporters and said imperiously, "Nobody can leave this vessel."

The moment was tense. "Capt. Ringk was supported by a number of his crew. While all hands were looking at the reporters one of them, who had one leg over the rail, suddenly swung the other leg over. The Captain made a grab at the reckless young man's coat collar. He considered the young man reckless, but the young man knew better. He had rapidly calculated the distance between the Fulda and the tug and had determined to make the jump. Before Capt. Ringk or his men could secure a hold on him the reporter had let go his hold on the Fulda and was in the air. A second later he had grasped the foremost stay of the tug and was safe on hoard. His brother reporters were grasped by a dozen hands before they could duplicate the feat, but in spite of the desperate efforts of the Fulda's crew the Times' men pulled their stories from their pockets and threw them at their fellow reporter on the tug. He caught them, and felt a great calm." there is much to be said for initiative.

Inevitably, under such circumstances as the loss of a vessel at sea, there are grave after-effects even when no fatalities are involved. In the case of the Oregon the two issues of primary concern were determining the cause of the accident and adjusting claims arising from the loss of the hull. cargo. and personal possessions.

Although there seemed no doubt that the Oregon collided with a vessel, it was suggested instead that she struck the masts of the Hylton Castle (q.v.), sunk two months earlier. Quick calculations and reference to the nautical charts indicated that the sunken hull lay at least ten miles away from the site of the collision. This begged the question then of which schooner was struck and what happened to her and her crew. This mystery has never been solved with complete satisfaction because the schooner or any parts of her have never been found and identified.

Beliefs at the time ranged far and wide. The New York Maritime Exchange began combing the records for ships gone missing. especially those whose proposed routes intersected the Oregon's path at the approximate time of the collision. This was a slow and tedious process of discovery since sailing ships often cruised for weeks between ports of call. and it was not uncommon for them to be delayed by the lack of wind or to stop along the way for repairs or provisions or to wait out bad weather. In fact, at that very time, more than two hundred loaded schooners were lying to in Hampton Roads because "The heavy northwest winds have made northern voyages in sailing vessels slow and perilous of late."

The job would have been half as difficult had it been known for certain that the schooner ( if it actually was a schooner and not a square-rigger ) was traveling east with the wind, implying that she was coming from a port to the south and heading toward a port in the north, and was at the time of the collision sailing with the wind in order to round Long Island. However, the lack of observation of navigation lights made some theorists wonder if the Oregon had not struck a ship which intended to proceed west but which, due to the strong headwind and ebbing tide, had dropped anchor to await more favorable conditions. in which case the Oregon would have stove in her stern. If that were true, the white light observed by the first and fourth officers could have been a binnacle light unmasked for a moment coincident with the collision, with the crew of the schooner unaware that they were about to be run down. this could explain why Matthews described the light as a "flash."

In the same scenario, the white light could have been an anchor light in the fore shrouds previously hidden from view by the masts and after shrouds. Then momentarily made visible as the Oregon's angle of observation shifted. It should be understood that the elevation of the Oregon's bridge wing above the water could conceivably place the officers at a height from which they might have to look down at the masthead light of a coasting schooner of a size such as the one which came to the liner's rescue, the Fannie A. Gorham. This could explain why the schooner was not seen from farther away. A thin haze would cloak a ship which was miles away on the horizon, where it would ordinarily be silhouetted against the sky. Then. once the ship got close enough to be in visual range, it could only be seen against the dark background of the water. As every mariner and small boat operator knows, the distance of lights seen at night is incredibly deceptive.

The case for a near-head-on collision seemed more persuasive. The evidence indicated that "The schooner was on the port tack, that is, with the wind blowing over her port side, and with her sails bellying out to starboard. The two vessels were approaching each other on the lines of an oblique angle." Mrs. Hurst's observation of a red light could be explained as a sailing ship's port running light. Among the dissenters of' this interpretation of events was the Chief Officer of the Dorset, who was quite emphatic: "I am morally certain from my own experience of 20 years that she couldn't have seen it through the dead light of her cabin, but that she saw what often deceived old mariners - the reflection of the light in her stateroom. I won't believe such a red light was afloat on the unsupported statement of any woman."

While it is true that lights are often reflected on glass, his comment appears to be more an indictment of the sex of the observer rather than what she claimed to have seen. I wonder if he was man enough to admit his prejudice when it developed at the official inquiry that the red light was also seen by at least two seamen who were dragging up mail sacks. Several seamen testified to seeing a white light, and one, William Howgate, saw a green light. Seaman John Rogers saw the jib-boom strike the hull, and quartermaster John Cunningham, who was stationed in the wheelhouse, distinctly saw a three-masted schooner under all sail except the headsails, which had been carried away. Thus it was established that the Oregon collided with a three-masted schooner which was displaying the required navigation lights.

Moreover, from the testimony of witnesses there seemed no doubt that the unseen schooner rebounded after first striking the Oregon. Then struck the liner's hull a second and a third time. Seafarers rushed to their blackboards and calculated that at the speed the Oregon was traveling she would have advanced a distance equivalent to her own length in about three seconds. which "would have carried her beyond a point at which a schooner could have struck her again." It might have looked good in chalk, but the figures did not fit the facts. With the schooner's sails full of wind and her masts in the act of crashing forward, by the evidence she must have recoiled with sufficient speed to account for the other two crashes.

Elsewhere it was estimated that the vessel "that struck the Oregon could hardly have been smaller than a one-thousand-ton schooner" which, loaded with coal, "would have gone to the bottom at once." the search for this unidentified schooner continued. More outlandish theorists surmised that the Oregon might have struck a mine ( at that time called a torpedo ) which had gone adrift from "somewhere" or which had been placed by wreckers hoping to cash in on salvage: or that "dynamite or some other explosive in her hold was exploded." the Oregon carried neither dynamite nor explosive of any kind, A coal bunker explosion was also ruled out.

As can be imagined, the sinking of the Oregon created quite a furor in the press, in shipping circles, and among the general populace. There was the usual hue and cry about the liner not carrying enough lifeboats to provide space for everyone aboard. Both Cunard and the Board of Trade insisted that she carried more than was required by law for a vessel her size. Nor was there official condemnation of the shortage of life belts; the Oregon had but 813 when she normally carried twice that many people. ( She also had 205 life rings .) Why is it, I ask, that it makes perfect sense to every human being in the civilized world to provide enough lifeboats for all passengers and crew, except to those who run shipping companies and who are empowered to enact laws for the greater safety of life at sea?

One self-professed expert. R.B. Forbes, made some rather short-sighted criticisms based solely upon newspaper accounts of the accident. Much of his advice was academic considering the outcome. For example, he thought that rescue craft should have tied off to the Oregon to prevent them from drifting away and that pumps should be fitted with manual overrides so that the muscle of steerage passengers but not passengers of first or second class ) could be used to pump out the holds by hand. Forbes also believed that ships should not slow down in fog, but should increase to their fullest speed because "The sooner we get over the many dangers in our path. The better in the long run." Imagine racing through a dense fog on the highway at eighty miles per hour in order to get out of the fog area sooner, and thereby lessening your chances of collision!

To give him credit where it is due, Forbes in his long career also proposed many sensible recommendations: the establishment of shipping lanes, the addition of airtight seats which would float off the upper decks when a ship went down, seat cushions which could double as floats ( like those in commercial aircraft today ), and a method of blowing off a ship's boilers not only to reduce the weight of the water they contained but to convert them to buoyant tanks which could conceivably extend the amount of time for a vessel to take its final plunge, thus allowing more time to launch lifeboats or to wait for rescue craft. If the Titanic could have remained afloat for a few more hours, the greatest maritime disaster in history might have become instead a famous rescue operation.

One British sea captain suggested that the Oregon's iron plating may have been made of a type called "pot metal" plate, which "has as much ductibility or pliability as plate glass." and which is therefore likely to shatter upon being struck rather than to dent or bend. This is not as outlandish a suggestion as it might seem, as many British vessels were constructed of such plate because it was cheaper to manufacture than the kind of plate which does not fracture when struck. Others promoted the use of steel plate for ships' hulls instead of wrought iron because steel is stronger. stiffer, and more elastic; also, more expensive.

Then there arose the question of why the Oregon did not steer for shoal water to the north, perhaps to be beached. The boiler fires were not instantly inundated. For this, there was no answer. Only because everyone survived did this issue not take on more importance.

Now every port community was concerned about overdue schooners. The first one nominated as a suspect was the Abbott F Lawrence, bound for Taunton, Massachusetts across the Oregon's path and a week overdue. This was three days after the accident. The next day more possibilities were added to the list: B.C. French, C.A. Briggs, Mabel Phillips, Job Jackson, Eva L. Ferris, Taulane, Charles H. Haskell. Spartan, Maud Sherwood, and Kloto. On March 19 the schooner Hudson, Philadelphia to Boston, became a potential victim.

Some concrete evidence came to light on March 20, when the fishing smack Henry Morgenthau picked up a schooner's yawl about twenty-five miles southeast of the wreck site. "The boat is a good one, built of cedar, and 30 feet long. The gunwale is painted black, the body white, and the bottom dark green. When found the boat was bottom-up. There are indications that she was hurriedly cut loose from the vessel to which she belonged. The painter and gripes and all other connecting tackle had been hacked through clumsily with a knife, and a plug which fits the hole in the bottom of the boat was found in the locker. The yawl bore no name."

That same day a large lot of wreckage floated past Asbury Park, New Jersey, and one-piece washed ashore: the cutwater of a sailing ship which "bore no marks by which it could be identified."

On March 24, fully ten days after the accident, and after many of the missing schooners had arrived at their destinations, their crews totally unaware of the collision or of the concern they had caused their shipping companies and loved ones, another vessel was posted missing: the three-masted schooner Charles H. Morse ( sometimes erroneously reported as the Charles R. Morse, which is a different vessel entirely ). The Charles H. Morse left Baltimore on March 6 with a cargo of coal bound for Boston. At Hampton Roads, she joined the company of the schooner Florence J. Allen. The two ships were in sight of each other until the night of the accident and in the vicinity of where the collision occurred. The Florence J. Allen arrived in Boston two days later, but nothing had since been heard of the Charles H. Morse.

The Charles H. Morse was 152.7 feet in length. had a beam of 36.2 feet, and a draft of 13.8 feet; her tonnage was registered at 508 gross tons. She was built in Bath, Maine in 1880, and constructed of oak and yellow pine. She was under the command of Captain Alonzo Wildes. Onboard as a passenger was her former master, Captain Alfred Manson. A mate and a crew of six completed the complement.

The Kloto was still unaccounted for. She left Baltimore on February 22, hound for New York with coal. To place her at the collision site on March 14. she would have to have been held up a long time by bad weather and to have taken a long eastward tack. The Kloto was never seen again, but shipping circles were inclined to believe that the Charles H. Morse was the schooner in collision and that the Kloto foundered. A wooden schooner grossing 508 tons sinking an iron-hulled mammoth grossing 7,375 tons is equivalent to a tricycle taking out all eighteen-wheeler. Stranger things have happened.

Then came a discovery which fairly well clinched the collision-with-a-schooner scenario. Three masts were discovered sticking out of the water southwest of Shinnecock Light. The Hydrographic Office assigned Lieutenant Field to investigate and take bearings. He found that the distance from the protruding masts to the wreck of the Oregon was sixteen and one-half miles, with the sailing ship lying southwest of the steamer. The depth of water at the site of the sunken sailing ship was 138 feet.

The Charles H. Morse being a small vessel, her masts "would hardly show above water if she lay on the bottom. An explanation of this is offered by the theory that she may have caught on a ledge or that the masts may be wrenched from their fastenings, and are now hanging by the shrouds."

Unfortunately for history, no positive identification was ever made of the sunken sailing ship. It could have been the Kloto or some other, larger vessel. If only a diver could have gone down and read her name board the proof could be positive instead of circumstantial. But at that time all available divers were busily engaged in salvaging what they could from the Oregon.

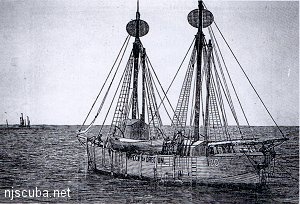

Cunard engaged the services of the Merritt Wrecking Company the day after the liner sank. The wrecking steamer Rescue located the wreck quickly because two of the masts protruded above the surface, the mainmast as high as fifteen feet. A third mast was standing just below the surface. The wreck lay at a depth of 130 feet.

The sea was adrift with flotsam. "Several pieces of baggage. six cases of dry goods, three life rafts, and a lot of life-preservers were found floating in the vicinity. Several mail bags, which were being tossed about by the rolling sea about four miles southwest of the wreck, were also picked up." Everything was taken to Cunard's offices for safekeeping except the mail bags. which were turned over to the post office for drying and delivery. The post office had its work cut out. A few of the densely packed letters were found to be dry, but most were soaked nearly beyond recognition, especially those letters written on thin, nearly transparent paper. Some 100.000 letters had to be spread out on tile floor and dried, then the bleeding inked addresses had to be deciphered. One letter from Cork was filled with shamrocks: three people showed up to claim it. but as the address could not be read none could have it. so it was sent to the Dead Letter Office. One package filled with cigars was confiscated because it was illegal to send cigars through the mail. One letter contained a will written on sheepskin; fortunately, the writing was still legible. Most. of the newspapers were ruined.

Pilot boats and other wrecking vessels found "a large quantity of wreckage, consisting of cases, barrels, mail bags, trunks, &c. The crew's of pilot boat T.S. Negus, No. 1, and of the brig Fidelia were engaged in fishing out the drift." the Francis Perkins, pilot boat No.13, scooped up thirty-five bags of mail. The SS Tonawanda picked up one bag, the schooner Henry Morgenthau another. About twenty-five miles off Barnegat. New Jersey, the brigantine Samuel Welch came across "life preservers, beds, oranges, and other small articles.." the schooner Nellie J. Dinsmore picked up two bags of mail and carried them to her destination, Portland, Maine, from which point they had to be shipped back to New York. The pilot boat Loubat brought in four packing cases marked B. & L. Two weeks after the collision the Coast Wreck Company's schooner Edwin Post fished up nine bags of mail. Eventually, more than half the mail was recovered, some by divers.

Pilot William Lewis was sailing in the vicinity of the wreck when he came across a mailbag which contained "$250,000 of Erie second consolidated bonds, addressed to L. Von Hoffman & Co. Mr. Lewis thought that he was entitled to salvage, and Von Hoffman & Co. offered him $500, which he declined to accept, deeming it an insufficient reward. His claim for salvage is still unsatisfied."

Because the masts presented a hazard to navigation, the Lighthouse Board marked the wreck with a lighted buoy. This was soon superseded by mooring a lightship next to the wreck. The lightship remained on station until November I 1886, by which time the Merritt Wrecking Company had knocked down the Oregon's masts and funnels, and there was at least 60 feet of water over the obstruction.

Divers sent down to examine the wreck immediately ascertained that total hull salvage was out of the question, for the hull was broken in two "abaft the fore rigging." there followed a period of unusually had weather which prevented divers from conducting a more thorough examination of the hull until mid-April. Then they "found that the vessel had broken in two between hatches Nos. 2 and 3. The after part of the hull had been twisted out of line from the forward part. showing that the vessel had probably sheered over as she went down and had then broken. About 25 feet aft of the break and in line with the fore part of the bridge was found the hole which had caused the vessel to sink. It was covered with canvas, which had been secured by two cords running under the keel, and five cords which had been attached to the rail. The canvas was cut away, and a break 6 feet long and 3 1/2 feet wide was found.

"The break commenced at two dead lights about 12 feet below the main deck. The iron plates of tile side bulged in at the hole and had smashed in some of the cargo, which was evidently steel or iron in boxes. No debris was found near the wreck, but along the middle line of the side fore and aft there were long scratches in the paint, which appeared as if they had been made by the fluke of an anchor."

Cunard had full coverage on the Oregon so the only loss the company incurred was unearned future revenues until a replacement vessel could be purchased or built. It was the responsibility of individual shippers and consignees to insure freight which belonged to them. But the passengers were left without recourse for the recovery of lost belongings beyond what Cunard was voluntarily willing to give them. Regarding such reimbursement. Cunard expressed the opinion that it would make fair compensation for losses if moderate claims were presented. The two key words here are "fair" and "moderate, " for the implication was that if the claimants were too many or asked for too much, Cunard would pay nothing.

Consider the plight of the poor immigrants who were traveling steerage with all they owned, arriving in the United States to begin life anew with nothing but the clothes they wore on their backs. They lost everything. But Cunard did not have to deal with them because they did not have the financial resources to put forth their claims. Cunard replaced their lost train tickets, then sent them on their way west: most were settlers bound for Minnesota, Nebraska, and Dakota. Those who hung around the offices pleading for money for lost clothes and personal belongings received no satisfaction, nor could they afford the services of a lawyer.

The first-class passengers were the ones who hired attorneys to seek restitution for personal effects which went down with the liner. And while I can certainly understand why one would not accept anything less than full replacement value for that fancy tweed suit or diamond brooch, I cannot help but point out the irony of the situation in which those who were so well off in life complained the bitterest about their losses.

Asked for an unofficial opinion on the matter, Chief Justice David McAdam replied, "The carrier across the seas of passengers or merchandise is not an insurer, and is not therefore liable for any loss of the goods entrusted to his charge without affirmative proof that the loss was occasioned by his fault or neglect. If the collision which caused the Oregon to sink was without any fault or neglect on the part of those in charge of the steamer, there is no responsibility on the owners either for the loss of goods shipped as freight or for passengers' baggage. If the ship had gone down by the 'act of God, ' such as a tempest at sea or a stroke of lightning, it is clear that no liability would attach, but as such was not the case with the Oregon, the question of responsibility hinges upon the determination of the question as to whose fault caused the loss, and this is a question of fact rather than of law.

"As a general rule, a steamer meeting a sailing vessel must take measures to avoid the latter, which has a right to keep its course. If, therefore, those in charge of the Oregon saw in time the vessel which collided, or if they might have seen it by the exercise of proper care and due diligence, then the collision was caused by the fault of those in charge of the steamer; but if, after exercising every care, those on board the Oregon, either by darkness or the fact that by reason of the sailing vessel not carrying proper lights, its presence could not be discovered in time, then, of course, those in charge of the steamer were not guilty of fault or neglect. In case of a suit against the owners, it would be sufficient, in order to establish a prima facie cause of action, to show that the baggage or merchandise was delivered to the steamer on the other side and that the steamer failed to deliver it here. This would cast upon the steamship company the onus of excusing the non-delivery. The company could only do this by affirmatively proving the fact of the collision and that it occurred without its fault. If it proved this, it would be a valid defense. If it failed to do so, its owners would be held liable for all losses."

Cunard was also slammed with a suit from North German Lloyd, which sought to capitalize on the Fulda's rescue efforts. Although the company charged Cunard no money for its services, it filed a salvage claim against the diamonds which the Oregon's purser had saved. The diamonds were taken to the Customs House where Deputy Collector Berry assumed charge of them. This meant that their owners, some of New York's finest and most well-respected jewelers, could not claim their goods until North German Lloyd's case against Cunard was settled.

These legal wranglings endured for years. Cunard's best defense against all claimants was a case then pending in the Supreme Court involving a collision between the Scotland and the Kate Dyer, which occurred in I 866. That's right, the courts had been trying to render a final decision for twenty years. The litigation was, as always, befuddling and labyrinthine, but the crux of the action was a statute which limited a ship owner's liability to the value of the owner's vessel after the accident ( and not against any of the owner's other vessels or holdings ). If the defendant vessel sank, as in the case of the Scotland and the Kate Dyer, the value of the vessel after the collision was essentially nothing. To make a modern analogy, if you owned a beat-up jalopy worth $500 and you smashed up two Cadillacs and a Rolls Royce then careened through a storefront and killed two people and started a lire which burned down the block, the most you would have to pay for damages would be the value of your vehicle after the accident. If the vehicle was totaled, you would walk away scot-free.

How supposedly sane minds managed to foist such an absurd statute on the civilized world is beyond me. Moreover, the statute was upheld, is still on the books today, and is often invoked in order to limit liability in maritime cases involving property loss.

Unfortunately, I was unable to find any court documents leading to a resolution of the Oregon's suit. However, since the British Board of Inquiry absolved the Oregon's officers from blame, the case was likely settled out of court to the dissatisfaction of all concerned. The passengers justifiably felt that, since the British court refused to hear testimony from the passengers, and heard testimony only from the officers and crew, the inquiry was a farce intended to whitewash the truth. Certainly, no reasoned and proper verdict can be reached in any case in which only selected facts are admitted into evidence.

Nor was that the only injustice dispensed. There was bureaucratic meddling as well. The Merritt Wrecking Company stored all salvaged goods and items in a warehouse owned by Bartlett, then, as was customary, tiled a salvage claim against them. The lot was sold at auction and the proceeds deposited in the name of the court to await disposition and disbursement. The Custom House collector, named Heddon. "put in a claim for duties, and when a second lot of goods were landed and libeled by Capt. Merritt, the Collector decided that the manner of waiting for the Government to get its money was too long. He decided to step in, sell the goods, deduct the duties, and turn what was left over to Capt. Merritt. When the sale took place Marshal Tate was present and informed the purchasers that they could not have the goods. as they had been seized under an attachment. The buyers didn't scare a bit, but bid off the goods and paid their money. When they sent to the storehouse for the packages, however, Marshal Tate would not give them up and the purchasers came back to Collector Heddon to complain. 'Pooh, ' said the Collector. 'Go get your goods. You have paid for them, and all you want is a "nervy" man to go and seize them.' A few days later the 'nervy' man went over to Bartlett's Stores, but there he met Marshal Tate and concluded not to take the goods. So the matter still hangs fire. The Marshal has the goods, the Collector has the money, and the purchasers have only receipts." Some things never change, and the petty contrivances of minor bureaucrats seems to be one of them.

Today the wreck of the Oregon is a broken down hulk, and it has been for quite a number of years.

( Photo by Mike DeCamp. )

Thirty years ago - in the mid-1960s - Michael de Camp wrote a popular article about what it was like to dive on the Oregon. That was eighty years after the sinking. Because the decks had long since caved in and the hull had completely collapsed, he described the wreck pretty much as it exists today. The major difference between then and now is not so much in structural deterioration as in the sheer abundance of artifacts which lay scattered about at the time. Loose portholes lay among great piles of china plates, bowls, and cups; and glass bottles were as numerous as weeds in a poorly kept lawn. Relics were there for the taking, and divers did not recover individual items but collected them by the bagful. This is difficult to imagine for today's divers, who see barren rusty hull plates with circular holes which were once occupied by brass portholes. and who thrill over the discovery of a broken bottle or china shard. Yet it was so.

Despite the ease with which divers used to stock their shelves with Oregon mementos, and the relative paucity in the volume of finds at the present time, the Oregon remains one of Long Island's most interesting and most visited dive sites--in addition to which divers now find artifacts far more unique and intrinsically valuable than any which have been found here. For those patient enough to pick a spot to "work" by fanning the sand or digging in the mud come the rare rewards of items which were previously buried or hidden by hull plates and therefore not accessible to the cursory explorers of yesteryear. Passengers' luggage, trunks, and suitcases have rotted away and left behind concentrations of personal articles such as gold rings, exquisite jewelry, brass buttons, silver coins, porcelain souvenirs, and innumerable belongings of unending variety. The major cache is in the starboard bow area, in what used to be the forward holds.