Lillian (2/2)

The Wreck of the Lillian

by John Geiser

Press Outdoor Editor

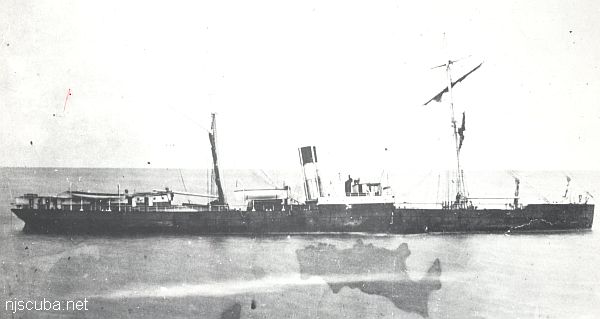

One of the most productive cod and pollock fishing spots in Shore area waters was created in a horrifying crash of steel on a foggy. February evening in 1939. Capt. Frank Boyer was peering through the glass of his wheelhouse on the 3,482-ton, oil-fired steam freighter Lillian at 6:53 p.m., Feb. 26 when he was shocked to see a larger ship bearing dead ahead only 100 yards away. The other vessel was the 6,568-ton North German Lloyd Line freighter Wiegand with Capt. Leopold Ranitz at the helm. Boyer later testified that he put his wheel hard over, stopped his engines, and went into reverse. Ranitz said he ordered full speed and attempted to maneuver out of the way. The tactics did not work.

The 238-foot American A.H. Bull Steam Ship Co. vessel drove its bow into the starboard side of the 370-foot Wiegand so violently that the steel plates of the larger vessel were rammed through the forecastle and out on the opposite side. The Wiegand had a huge gash torn in her side, but it was above the reach of the fairly calm seas. The Lillian, on the other hand, was badly damaged in the bow and began taking water rapidly. Boyer identified himself to Ranitz and checked for damage. At 7:12 p.m. he felt the Lillian was sinking and that he must abandon ship. A wireless SOS was sent immediately. The Wiegand stood by to help.

William Hembold, wireless operator on the Lillian, continued to send the SOS signals until Boyer decided that the vessel would stay afloat only 10 or 15 minutes more. With the water lapping around his ankles, Hembold locked his wireless key on a continuous homing signal to aid rescuing vessels and abandoned the ship with Boyer less than two hours after the collision ...

The Wiegand picked up the first 11 men in a deepening fog and rescued the second lifeboat load of 15 men shortly before 10 p.m. There were no injuries. Meanwhile, the Coast Guard cutter Campbell and several other ships rushed toward the scene of the original collision some 13 miles from the Barnegat Lightship, and, strangely, the Lillian remained afloat, drifting north-northeast.

The Lillian had been en route from Puerto Rico to New York City with a cargo of sugar. One of the first vessels to join the Coast Guard cutter on the scene was another Bull Line vessel, the Emilia, also carrying sugar from Puerto Rico. The Wiegand, with a load of scrap iron destined for Moji, Japan, turned at this point and limped back to Pier 5, Brooklyn.

But the Lillian proved to be more buoyant than expected. At 3 AM, the vessel was still afloat with its radio shrilling its signal over the airwaves. The Coast Guard finally silenced the radio by shooting the insulators off the Lillian's antenna. The Lillian continued to settle slowly, but it was not until a salvage ship, the Relief, had steamed from New York to within the length of a football field of the stricken vessel that it finally disappeared beneath the surface, over 18 hours and 17 miles from its position at the time of the collision. It was 25 miles from Manasquan Inlet.

And there the Lillian rested for 20 years, its position unknown to anglers. But following the war, party and commercial boat owners began to utilize some of the early sonar and long-range navigation systems developed during the war. Instead of a compass and an alarm clock to find fishing spots, the boats were equipped with depth recorders and Loran-A systems.

They ranged farther and farther offshore looking for better fishing. Capt. Howard Bogan, a skipper in his 20s at the time, was fascinated with the new electronic equipment and what it could do. His Jamaica out of Bogan's Basin, Bride, was fitted with the latest gear and he used it to find wrecks, rocks, and ridges beyond the traditional inshore grounds. "It was a challenge," he said. "We were all looking for new wrecks, and I found a lot of them. I loved it, and we always tried to keep them a secret."

One of the wrecks be was interested in was the Lillian. He had heard of its sinking, knew where the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey said it was supposed to be ( it was actually three miles away, ) and had looked for it on occasion. He found numerous other wrecks, including the famous Resor, but he did not find the Lillian.

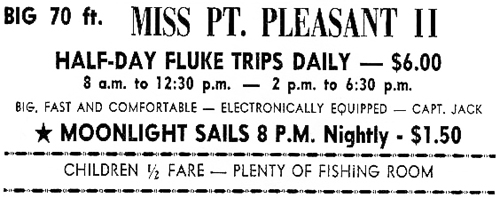

Capt. Jack Endean, skipper of the Miss Point Pleasant II out of Ken's Landing, Point Pleasant Beach, at the time, also knew about the Lillian, but had never actually looked for it. Then, in 1956, he learned from Neils Rassmunsen, captain of Edwin I. Osmundsen's Elsa C, a commercial dragger out of Point Pleasant Beach, of a big wreck that the commercial men knew as the "Dutchman."

Rassmunsen had found the wreck by accidentally hanging his commercial gear in it some 25 miles from Manasquan Inlet. The wreck was in roughly 150 feet of water, and he gave Endean the Loran-A numbers to find it. "I had the numbers for a couple of years, but the wreck was a ways offshore for us in those days, and I didn't go out looking for it until sometime in February of 1958," Endean said.

On that day he had only seven fishermen aboard and they suggested that he look for the Lillian while they played cards in the cabin. The agreement was that, even if he did not find the wreck, they would pay for a fishing trip. Little did they know that it would probably be the fishing trip of their lives. "I ran out and started making figure eights and found it in less than an hour," Endean said. "There it was, big as life. Kenny Keller ( present captain of the Norma K III out of Ken's Landing ) was mate on the boat then and he was so excited he almost threw the buoy through the wheelhouse window. We anchored right on it."

The card game was forgotten in minutes. The action was furious and the fish big. "It was the best wreck I'd ever fished on," Endean said. "Every time you dropped down you had a fish on. It was loaded with cod and pollock" When they returned to the dock with the huge catch, which included cod to 50 pounds and pollock to 30 pounds, the word. spread like a brush fire in a high wind: Jack Endean had found the Lillian!

The find and the great catch made headlines on outdoor columns throughout the state. Everyone with a yen to fish for cod and pollock wanted - to fish the Lillian, which immediately created a problem for Endean. He wanted to keep the wreck's location a secret, but fishing was not good that winter, and other captains, particularly Howard Bogan, wanted to fish the Lillian. They were watching Endean and his Miss Point Pleasant II. "It blew northeast for a couple of days; so we didn't get out," Endean said. "The third day I fished the Tolten and the Logwood (wrecks), trying to keep it a secret; then I had to go back to the Lillian. The people were ready to kill me; they were saying I didn't find a wreck and so forth."

Endean was first out of the inlet that morning and anchored over the Lillian before the Jamaica appeared on the horizon. "I was about four miles away when Jack saw me," Bogan said. "But I had heard the depth of water the Lillian was in, and I knew about where it was. I was coming out that morning to find the Lillian." Endean hurriedly picked up and left the scene to fish elsewhere, but the Lillian was a secret no longer. "The Lillian is tough to find even after you know where it is and have fished it," Bogan said. "I ran right over it on the first shot."

Using his Loran-A and his old Bendix depth recorder, just as Endean had, Bogan anchored on the wreck and then called his brothers, John and David, who were fishing in the Mud Hole nearby with the Paramount II and Pennsy, respectively. Endean quickly came back, and as Bogan described him: "He was wild," but added "It happened to me on the Resor. That's part of the game."

The four skippers shared the wreck for the rest of the winter, consistently bringing in heavy catches of cod and pollock and the spot has remained productive to this day, not only for the winter species but also for sea bass, ling, bluefish, bonito, tuna, and albacore. "We always had trouble finding it until we got better equipment," Endean said. "Sometimes we'd circle around for a long while before someone would locate it." Bogan explained that after a few days they worked out a system whereby the first boat to find it would be allowed to anchor without hurrying, but leaving enough room for the second.

While the party boat captains had an idea what lay on the ocean floor, the true picture of the Lillian today is best described by veteran scuba diver Steve Nagiewicz, a scuba diving guide and owner of the 30-foot dive boat Diversion out of Point Pleasant Beach. "It's a big underwater junkyard today," he said. "I dive on it three or four times a year. I was out on it Sept. 10 and there were fluke, codfish, small pollock, sea bass, sea robins, ocean pout, and lobsters on it."

It is believed that the wreck has been hit with Navy depth charges, wire-dragged by the Coast and Geodetic Service, ripped by the nets of Soviet trawlers, torn by scallop dredges, banged by countless anchors, and laced with the nets of many small domestic trawlers. "It's a metal graveyard, covered with mussels," Nagiewicz said. "It lies on a flat plane with the bow up at a 40- to 50-degree angle. it comes up about 20 to 25 feet, but the rest is pretty hard to identify. "With the boilers and engines you can get an idea of their location because of their height, but there are metal plates on top of each other all over and nets and lines and cables are draped over them.

"It's full of derelict lobster pots and it's covered with monofilament line," he said. "Two weeks ago we were out there and our anchor got stuck in two or three pounds of monofilament." He said the wreckage is spread over 300 to 500 feet on the ocean floor now, though it still retains the general layout of a ship.

"It's pretty much fallen apart," he said. "But you can still find artifacts there, portholes and valves and things, and there are still plenty of fish on it. The cod like to hide in all of the holes." Nagiewicz said the wreck is in 156 feet of water. Most boaters with modern Loran-C navigation equipment and accurate depth recorders have little trouble finding it.

Divers claim the Loran-C numbers for the Lillian are 26xxx.x and 43xxx.x, but Endean says they are 26xxx.x and 43xxx.x, a small difference, but perhaps fitting for a wreck that was so hard to find for so many years.

Questions or Inquiries?

Just want to say Hello? Sign the .