Northern Pacific (2/2)

Chapter 29: Northern Pacific

reprinted from Shipwrecks of Delaware and Maryland by Gary Gentile

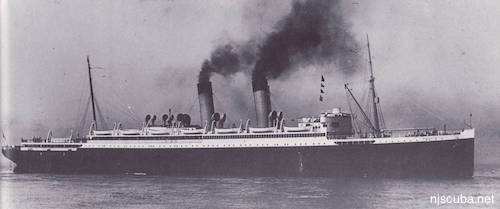

| Built: | 1915 |

| Previous names: | None |

| Type of vessel: | Liner |

| Gross tonnage: | 8,256 |

| Dimensions: | 509' x 63' x 21' |

| Power: | Three oil-fired steam turbines |

| Builder: | William Cramp & Sons, Philadelphia PA |

| Owner: | U.S. Govenment ( Army Department ) |

| Sunk: | February 8, 1922 |

| Cause of sinking: | Fire |

| Depth: | 140 feet |

The Northern Pacific and her sister ship, the Great Northern, were originally built for the Great Northern Pacific Steamship Company, which itself was an extension of James Hill's Great Northern Railway. The sumptuous liners could accommodate 550 first-class passengers, 108 second-class, and 198 third-class; each carried a crew of 224.

During the summer the sisters ran between Flavel ( near Astoria, ) Oregon, and San Francisco; in the colder months, they steamed the San Francisco-Honolulu route. At twenty-three knots, both sisters set speed records that held for years afterward.

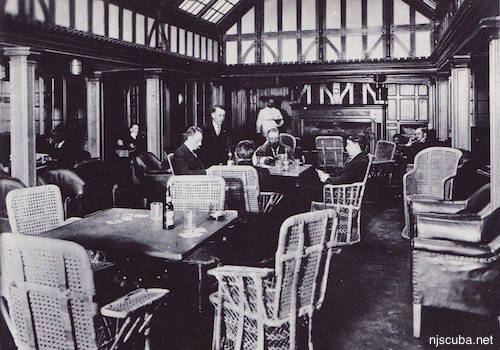

When America entered the Great War, the U.S. Shipping Board took over both triple-screw vessels for use as troops transports. The peacetime furnishings were removed, luxurious staterooms were converted into barracks, and all provision was made for the increased number of passengers, including solid-core life rafts lashed vertically onto the boat deck. The Northern Pacific was commissioned into the U.S. Navy on November 3, 1917. She was armed with four 6-inch guns, two 1-pounders, and two machine guns. She now boasted a crew of 420 men and forty officers; during one transatlantic crossing, she carried as many as 2,780 soldiers. The cooks worked overtime.

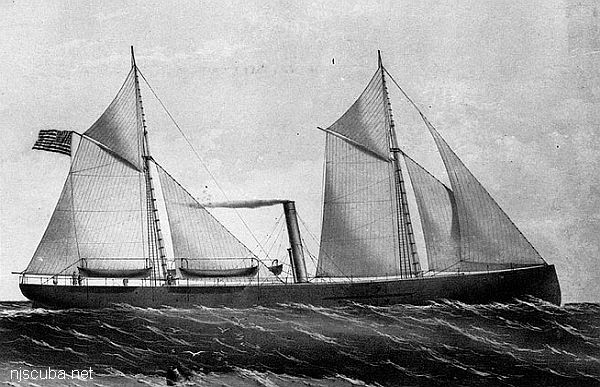

( Both courtesy of the San Francisco Maritime Museum )

( Courtesy of the San Francisco Maritime Museum )

The Northern Pacific made an admirable service record. During eleven round trip voyages between New York and Brest, France she carried 22,866 troops and passengers "over there" and returned 5,683 wounded soldiers. She was fast enough to outrun any U-boat, and because of her speed was soon dubbed the "Ghost Ship."

During one trip to Brest ( in September 1918 ) an epidemic of influenza broke out on board. Sickbay was overflowing, so cots were set up in the corridors and the brig. Seven soldiers died during the crossing, as well as three crewmen; 350 stretcher cases were put ashore in France. The bodies of the dead were brought back to the States.

Another disaster struck on January 1, 1919. She was returning to the States with 2,973 servicemen, most of whom were wounded or sick, when she ran aground off Fire Island in a dense, nighttime fog. With so many patients aboard, the Navy wasted no time dispatching help. Doctors were sent by train, while the hospital ships Solace and Seneca, the troopship Mallory, the cruiser Des Moines, a dozen destroyers, and a fleet of sub chasers and naval tugs rushed to the scene.

Lifesavers from the Point O'Woods, Oak Island, and Fire Island stations converged with their equipment on the beach opposite the stranded vessel. The sea was calm, but they shot across a line for a breeches buoy should the weather take a sudden change for the worse. A surfboat put out from shore; lifesavers found the ship in no immediate distress, and the men enjoying a happy New Year's party.

Only sub chasers had a shallow enough draught to get inshore of the Northern Pacific. Most of the bed-ridden sick and stretcher cases were transferred to these boats by basket litter; some ambulatory patients came ashore in the surfboats. One boat capsized, and it was only through the heroic efforts of Lieutenant John Roullot, who jumped into the frigid water three times, that there were no casualties. The entire operation took four days. Everyone was offloaded safely.

Seamen Percy Eger and Glenn Gates described the salvage operations:

"Three tugs were employed at each tide to pull on each side and we had five kedge anchor lines made fast to our heavy hawsers. We pulled on these, and if there was any slack we held it. Barges were sent out from New York and we commenced putting liferafts, boats, boat davits, and our four six-inch guns aboard of them to lighten the ship. We also cut our signal towers down. The ship would move astern and out toward deep water at each pull. Some pulls were made as follows: Sixteen feet, 9 feet, 20 feet, 11 feet, 60 feet, 107 feet, 2 feet, and so on. After about ten days it began to look as if we were to stay on the sand for a good while. Finally, on the evening of the 18th, at 8:05, we had moved 250 feet, and a little later she started to move more rapidly, and at 8:57 P.M. she was afloat. The crew went wild with cheering and you never saw a happier bunch in all your life, for we had spent 18 days on the sand."

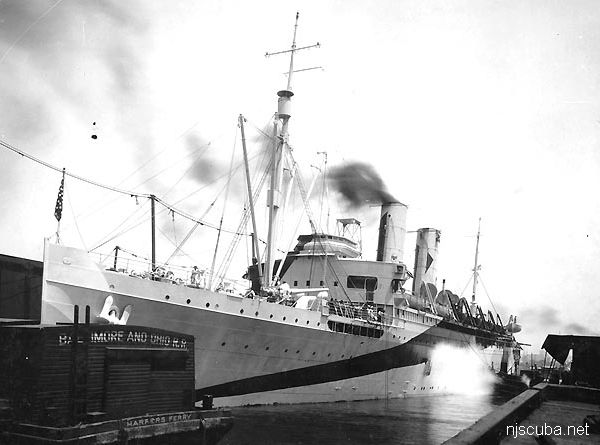

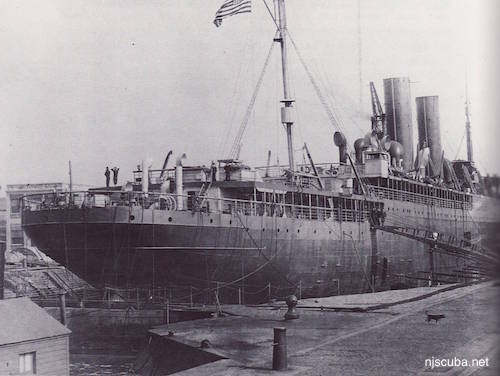

( Courtesy of the San Francisco Maritime Museum )

( Courtesy of the Naval Photographic Center )

The Northern Pacific was towed to New York and drydocked at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Her sternpost and after frames were severely damaged, requiring more than six months of repair work. By that time the Navy no longer needed her. On August 20, 1919, she was decommissioned from the Navy and transferred to the Army Transport Service, which she served for the next two years.

The New York Times later reported that "on Jan. 20, 1920, the transport was returning with the last contingent of American troops from France when she picked up an S.O.S. call from the American steamship Powhattan, which was drifting helplessly off the Nova Scotian coast, and rescued her passengers and brought them to New York. In the summer of the same year, the Northern Pacific was carrying General John J. Pershing on his trip through the Antilles when she went ashore at the entrance to the harbor of San Juan, Porto Rico, closing the port for several days until she was hauled off."

On November 22, 1921, the Northern Pacific was returned to the Shipping Board, which sold her on February 2, 1922, to the Pacific Steamship Company ( Admiral Line. ) The Shipping Board agreed to pay half a million dollars to have the ship reconditioned for passenger service, and for that purpose she was to sent to the Sun Ship Building and Dry Dock Company at Chester, Pennsylvania.

At 6 p.m. on February 7, with a skeleton crew of twenty-eight men, the Northern Pacific pulled out of her New York pier and headed south. The run was expected to take twelve hours.

Shortly after midnight, officer of the watch A.B. Wilson thought he smelled smoke and reported it to Captain Lustie in the chart room. The captain instructed First Officer Jellison to check it out. Jellison followed the pungent odor aft and down several decks until he ran into thick, black smoke pouring out of the lower holds. He had to crawl back on his hands and knees. He raced for the crew's quarters to warn off-duty personnel of the danger.

Meanwhile, Captain Lustie took over the bridge and ordered Wilson to assist Jellison in his inspection. So fast had the fire taken hold that Jellison's route was cut off. Wilson was nearly overcome by flames and smoke boiling out of a companionway common to all decks. The entire midships was a burning cauldron. "While reporting this to the master on the bridge it was necessary to shut themselves in the wheelhouse to avoid suffocation." Wilson said that he "thought the ship was gone." This was no more than four minutes after the first indication of trouble.

Captain Lustie ordered an immediate turn toward shore, twenty miles away. The new course had not yet been steadied when the lights died and the telemotor blew out; the helmsman was injured by the blast, and the captain no longer had control of the ship's rudder. There was no communication with the engine room, either by telegraph or speaking tube. The stern of the ship was cut off by the blaze. Jellison returned, with a report that agreed with Wilson's. The smoke was now so thick in the wheelhouse that the men were forced outside.

As the ship lost way and swung broadside to the wind, the men swung out and lowered No. 1 lifeboat. The captain ordered Jellison and four men to take the boat aft and take off the engineers he hoped were mustered on the other side of the blaze. Heavy smoke engulfed No.3 lifeboat, but No. 4 was cleared away and lowered, again with instructions to head aft.

Captain Lustie remained aboard with No. 2 lifeboat for nearly an hour, until the entire boat deck was aflame. He reluctantly abandoned ship. Not knowing whether the rescue had been effected aft, he and the men with him tried to steer along the hull toward the stern. But because of high winds, the ship drifted faster than the lifeboat, and soon the captain's boat was swept away.

Nearby, from the bridge of the SS Transportation, Captain Seth Chase saw a ship that "was in flames from end to end. We made all speed to her assistance. "

At 2:45 a.m., Captain Lustie and his men were picked up by the Transportation. Already aboard were the First Officer and the men from NO.1 lifeboat. Half an hour later, they came upon a motor launch that had onboard the Chief Engineer and a dozen crewmen who had been stranded on the Northern Pacific's fantail. A few minutes later they received a radio call from the SS Herbert G. Wylie that she had picked up No. 4 lifeboat. When the roll call was entered, four men were still missing: employees of the Sun Ship Building Company whose cabins had been situated just above where the fire had broken out.

Captain Chase maneuvered the Transportation close to the Northern Pacific's stern. Searchlights stabbed out at the burning decks, but there was no sign of life. After dawn, the Transportation again approached the liner, with the same result. Captain Chase maintained a constant vigil on the burning ship until nearly 10 a.m. when he proceeded on his way to Newport News. At that time the liner was listing thirty degrees.

The Coast Guard cutter Kickapoo arrived at the scene and continued the lookout for survivors. She searched as far as fifteen miles down current for rafts or floating men. When she returned to the drifting ship, the heat emanating from the red-hot hull was so intense that the Kickapoo could approach no closer than a quarter-mile. The cutter was still standing by at 3 p.m. when the Northern Pacific rolled over and sank.

The four Sun Ship men were presumed to have been overcome by smoke and to have gone down with the ship.

A Department of Commerce board of inspectors was unable to ascertain how or precisely where the fire started. The Northern Pacific was valued at nearly two million dollars; insurance had been transferred at the time of sale.

The wreck of the Northern Pacific was first dived in 1967, by John Dudas and Bill Scheibel. They were looking for the destroyer Jacob Jones, whose wreckage at that time had not been located. In the course of checking out unidentified obstructions, they accidentally wound up on the liner. Scheibel later identified the Northern Pacific from his first-hand exploration of the sunken hull, and by matching accounts of the position of her sinking with the location of the wreck.

The three huge propellers were still in place at that time and must have presented an impressive sight. They were later blown off and salvaged.

Because of the distance from shore, the Northern Pacific is often overlooked as a prospective dive site. Over two decades after her discovery she remains relatively unexplored. Yet, she is a fascinating wreck to behold. Her upside-down hull is almost perfectly intact, although several broad breaks allow access to the interior; one large crack bisects the engine room. The starboard side of the wreck appears like a long vertical wall right down to the level of the sand and runs unbroken nearly the entire length of the ship.

The port side is ripped outward, exposing her portholes (many of which lie loose in the sand) and offering a place to crawl under collapsing steel plates to the vast interior. It is along here that divers concentrate their efforts; large lobsters are found in the debris field that extends out into the sand.

As the wreck continues to deteriorate it will become even more exciting to explore. Falling hull plates will eventually allow easy access to the inside corridors and machinery spaces where a wealth of brass artifacts lie waiting to be recovered.

The Admiral Line also bought sister ship Great Northern (known as the "Galloping Ghost") and re-converted her for passenger service. She served in that capacity for nearly two decades. At the outbreak of World War Two, she was again taken over by the U.S. government for use as a troop transport, this time under the name of George S. Simonds. After serving admirably in two world wars, she was ignominiously scrapped in 1948.

GARY GENTILE'S POPULAR DIVE GUIDE SERIES

Shipwrecks of Delaware and Maryland

As suggested by the title and series name, this volume covers the most well-known wrecks sunk off the geographical coasts of Delaware and Maryland.

For each of the wrecks covered, a statistical sidebar provides basic information such as the dates of construction and loss, previous names ( if any ), tonnage and dimensions, builder and owner ( at time of loss ), port of registry, type of vessel and how propelled, cause of sinking, location ( loran coordinates if known ), and depth. In most cases, a historical photograph or illustration of the ship leads the text. Throughout the book is scattered a selection of color underwater photographs, some of the wrecks, more often of typical marine life found in the area.

Each volume is full of fascinating narratives of triumph and tragedy, of heroism and disgrace, of human nature at its best and its basest. These books are not about wood and steel, but about flesh and blood, for every shipwreck saga is a human story. Ships may founder, run aground, burn, collide with other vessels, or be torpedoed by a German U-boat. In every case, however, what is emphatically important is what happened to the people who became victims of casualty: how they survived, how they died.

Wrecks covered in Shipwrecks of Delaware and Maryland (2002 Edition) are:

DELAWARE: Asenath A. Shaw, B.F. Macomber, Brinkburn (and Siam), Brooklyn, Cherokee, China Wreck, City of Georgetown, Cleopatra, Crystal Wave, De Braak, Elizabeth Palmer, Faithful Steward, Gypsum Prince, Hvoslef, India Arrow, Jacob Jones, John R. Williams, King Cobra, Misty Blue, Mohawk, Moonstone, New Orleans, Nina, Northern Pacific, Poseidon, S-5, Sarah W. Lawrence, Singleton Palmer, Southern Sword, Sutton, and Thomas Tracy

MARYLAND: African Queen, Blenny, Galga, Gordon C. Cooke, Manhattan, Muff Diver, Oklahoma, Saetia, San Gil, Solvang, St. Augustine, Washingtonian, and W.L. Steed.

Plus there are two bonus sections: one on Unidentified Wrecks, and one on Artificial Wrecks.

To order this book and others like it, visit Gary Gentile's website at https://ggentile.com

Questions or Inquiries?

Just want to say Hello? Sign the .