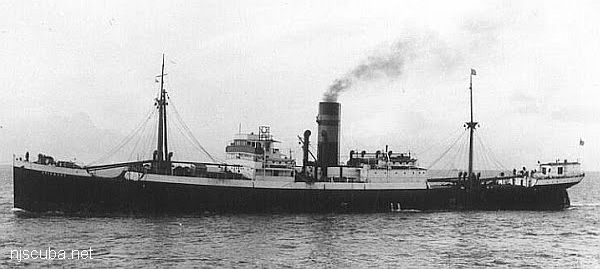

Miraflores

- Type:

- shipwreck, freighter, Britain

- Built:

- 1921, England

- Specs:

- ( 270 x 39 ft ) 2755 gross tons, 34 crew

- Sunk:

- Thursday February 19, 1942

torpedoed by U-432 - no survivors - Depth:

- 165 ft

Lost Without a Trace

The mystery of the S.S. Miraflores is solved

text & images by Gene Peterson - Atlantic Divers

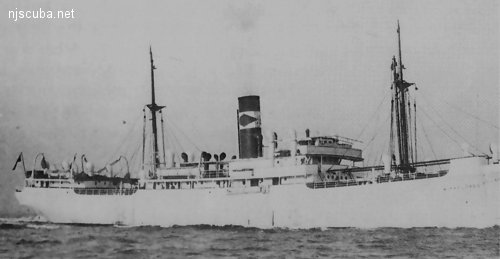

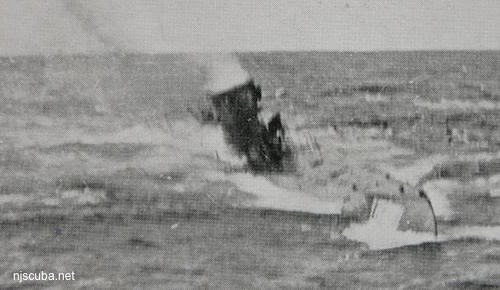

It is February 19, 1942. In the darkness of the cold winter morning, the stealthy German submarine U-432 follows the silhouette of a lone freighter steaming north fifty-five miles east of Cape May, New Jersey. The order to man battle stations is relayed to the crew. Onboard the British steamer, most of the crew members are off duty, settled in their bunks sleeping in the early morning hours. The drone of the pounding steam engine is abruptly interrupted by the detonation of two torpedoes that slam into the targeted ship. Within minutes the force of the sea draws the tortured hull to the sandy bottom. Thirty-four merchant sailors are lost without a word relating the circumstances of their deaths. Only a short entry in the German U-boat's log gives a vague description of the victim with no name. The next day the S.S. Miraflores is reported missing after failing to reach her final destination, New York.

Owned by Standard Fruit Company, Miraflores normally carried a cargo of assorted tropical fruits such as bananas, coconuts and cashews between New Orleans and Central America. On February 6, 1942, Captain Charles Thompson of the S.S. Miraflores left port on a change of orders. These new orders were to dramatically affect the fortune of Captain Thompson and his crew. The S.S. Miraflores was destined to become one of the hundreds of victims lost during the start of World War II. Thompson was to sail to Haiti to load the vessel with a cargo of assorted fruits then sail for New York. On February 14, the vessel departed and was sighted the next day en route by a passing ship. S.S. Miraflores was not seen again until the freighter was discovered and dived nearly fifty years later.

U-432 was credited with sinking the freighter Miraflores, although his logbook entry has no named vessel, only an estimated tonnage. At 3:18 a.m. Schultze positioned his submarine perpendicular to the little fruit ship steaming north and fired two torpedoes. Both struck the freighter with a united explosive power. The first torpedo struck forward of the wheelhouse cutting the ship in two which left the bow intact. The second followed striking amidships obliterating the stern forward of the aft deck house. It is probable that this enormous explosion caused the S.S. Miraflores had to sink within a few minutes.

The possibility of the crew escaping the doomed sinking ship was nil. Had anyone survived the tremendous blast, the icy cold water, and confusion in darkness diminished all hopes of escape to less than a few minutes. Hypothermia would spare no one in such an inhospitable frigid sea so far from land. No distress call could be made due to the direct and devastating blast near the bridge that probably stunned or killed all officers and crew in that proximity instantly. For Captain Thompson and his crew, their luck had run out. There was no hope of rescue this night in the bitterly cold North Atlantic.

By the 20th of February 1942, the S.S. Miraflores failed to report in New York and it was soon evident that her loss was to remain a mystery until investigations by the U.S. government after the war. Even then it was deduced that the ship was torpedoed, but the exact location was based on speculation. It remained that way for several decades. Families would find few answers if any from the shipping company or from any government agencies. Soon the S.S. Miraflores was to become buried beneath the sands of the Atlantic Ocean and her memory was to be muttered only by an occasional word from the faded memories of those that were directly affected by her sinking.

In 1992 Bill Dumeze the captain of the red-hulled clammer Arlene Snow ran over a snag while fishing. He contacted Jim Bowen, an avid wreck fisher, and the two left Cape May inlet following only a compass bearing to the wreck site. Jim believed this was going to be some wild goose chase because Bill had recorded no Loran numbers. After four long hours steaming at 12 knots to the middle of nowhere Captain Bill told Jim to slow the boat down and follow his bearings as he scanned the bottom finder. After what seemed to be a convoluted course of bearing changes over a period of a half-hour, Bill shouted to drop a buoy.

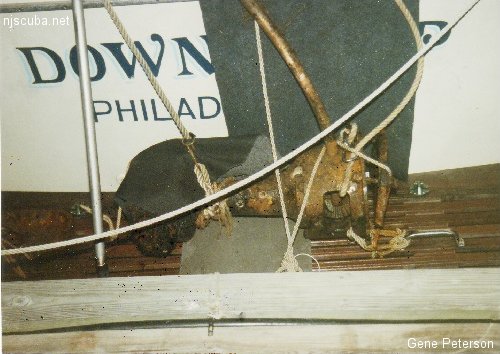

Jim Bowen looked over Bill's shoulder as a large spike appeared on the screen that looked like an ice cream cone with a sprinkle of jimmies. These were in fact fish hovering over the virgin wreck. Jim was amazed that anyone could find a wreck scanning a depth recorder with no land bearings. Bill explained that clammers and scallopers know the bottom of the ocean well, spending 99% of their time looking at the depth recorder searching for their harvest. Jim gave the wreck its first nickname the "Ice Cream Cone". I was able to match the serial numbers from a helm recovered in 1994 from the wreck with a tragic war victim of 1942. The long-lost Miraflores was finally found. The wreck is also known as "Bob's Cold Spot."

Questions or Inquiries?

Just want to say Hello? Sign the .