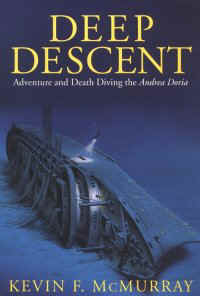

Andrea Doria (5/7)

Chapter Two:

The Wreck Of the Andrea Doria

reprinted from Deep Descent, by Kevin McMurray

"Despite all the safety gadgets, the mind is supreme

and the mind is fallible."

- Captain Harry Manning, SS United States

The eastern and central section of New York's Long Island is a myriad of expressways, parkways, and turnpikes, the kind of urban sprawl that enlightened city planners love to point to as the epitome of poor vision. You have to look no further than Jericho Turnpike to understand their thinking. Flanking this multi-laned blacktop, whose serpentine path winds eastward to the more benign and pastoral stretches of eastern Long Island, is a seemingly unending string of fast-food restaurants, auto-body and muffler shops, and gas stations. Then smack dab in the middle of the concrete morass in the town of Syosset, there is the Caracalla Restaurant.

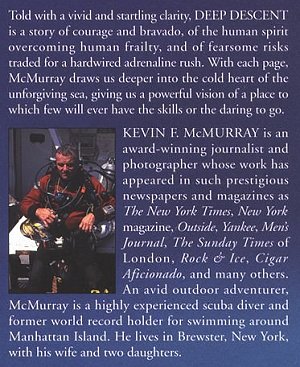

The Caracalla's faux Italian Renaissance decor may strike some as kitschy, but it is a welcome visual respite from the glut of indistinguishable architecture that greets the eye on the Jericho Turnpike. The free-standing building is overseen by chef Vincenzo Della Torre, surviving first-class sous-chef of the Andrea Doria.

Vincenzo is a little man, not more than 5'2". He is 66-years old and spry for his age. He has that debonair European demeanor and the Italian propensity for wrapping his arms around perfect strangers. On my first visit, he escorted me to the bar and without sparing a word asked me, "Who do you think was responsible?"

I had come to talk to him about his experiences aboard the Doria and what happened that night, I was not ready to render a decision about where the blame was to be laid. But in his embrace and under his piercing stare I uttered, more out of intimidation than anything, that it must have been the Stockholm's fault for sending the ship to the bottom. It did, after all, I reasoned, breach the Italian beauty's vitals with its ice-breaking bow, analogous to broad-siding another automobile at an intersection after running a red light. He smiled and patted me on the back. It was the answer he wanted to hear.

Dressed in his kitchen whites, with a kerchief nattily tied around his neck and his balding pate ribboned by a wisp of graying hair and a goatee impeccably maintained, I could envision him hard at work over a stove on the flagship of the Italia Line almost a half-century ago.

Vincenzo hosts a yearly party for Doria survivors at his restaurant on the anniversary of the sinking. "It was the best ship in the world", he told me as he told anyone who asked, "but everybody knows that. But the thing is when you write this book you got to tell the truth about what happened. Captain Calamai was right."

A natural response for the aggrieved, one might suppose. Vincenzo Della Torre was no sailor. He was a 22-year old cook aboard a luxurious ocean liner and knew little about the intricacies of maritime right-of-way. But who was to blame for the sinking of a pride of a nation is serious business to people like Della Torre. And rightly so. The Andrea Doria was not only a magnificent ship, she was emblematic of the times, and most of all she was the product of a proud people from a struggling nation who wanted the world to see that it was still capable of producing a masterpiece.

Genoa has always been Italy's window to the sea. Once a mighty city-state that rivaled Venice for power and prestige in the Mediterranean, Genoa produced Italy's two greatest mariners, Christopher Columbus and Andrea Doria (1468-1560). While Columbus' name is more recognized around the world, Andrea Doria had the more swashbuckling career.

Doria was captain-general of the Genoese navy from 1512 until the city was taken over by the Spaniards in 1522. By 1528 he helped restore independence in allegiance with the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. Once liberated from the oppressive yoke of Spain, he went on to lead the sea battles in the bloody wars against the French and the Barbary pirates. Andrea Doria also helped Charles V capture Tunis and saved the Holy Roman Empire from a disastrous expedition against the North African city of Algiers in 1541. As a statesman, he was not above immersing himself in the bloody Genoese feuds and conspiracies. Much like his American counterpart George Washington, Andrea Doria is often referred to as "The father of his country." Doria is also credited for being the first mariner to devise a method for sailing a ship against the wind.

After a distinguished career, Andrea Doria retired to a monastery at 87. Such monastic retreats were the rewards for exemplary public service, but his service to his city was not over. When France tried to annex the nearby island of Corsica, Doria was called to duty and once again successfully led the fleet to victory. Andrea Doria finally died at 93, an extraordinarily long life at the time.

None too surprisingly the name Andrea Doria would grace the transom of many an Italian ship. A brig called the Andrea had the honor of being the first foreign ship saluted by the independent United States.

In 1949 Italy was still struggling to raise herself from the ruins of World War II. World tourism was blossoming and bringing incredible wealth to many nations. Italy had many cultural and architectural treasures to lure tourists to her shores. The reconstructed country turned to Genoa, to provide a vessel of transportation to bring hordes of dollar-laden tourists to Italy.

There was plenty of competition for transatlantic tourism: England, France, the Nordic countries, and the United States all had stately ships to entice travelers. Not to be outdone, the world-famous Ansaldo Shipyards in the Genoese suburb of Sestri laid the keel for what was to be the most elegant ship of her time, to be named after the naval hero, statesman, and innovator Andrea Doria. On May 22, 1950, to the cheers of the proud Genoese, the newly christened Andrea Doria slipped into the shimmering waters of the Ligurian Sea.

It took another eighteen months for the ship to be outfitted for transatlantic service. The owners of the ship, the Societa di Navigazione Italia (Italia Line), decided against competing with the British and the Americans in building the largest and fastest of ships. Instead, the Italia Line wanted to entice their passengers with luxury and art and built what was to later be described as a "floating art palace." they also wanted their ship to incorporate the latest techniques in shipbuilding, and spared no expense.

The Andrea Doria had a revolutionary design: the fore-body section incorporated a radical flare, which terminated forward in a knuckle and a bulbous bow - a feature designed to reduce drag and increase speed. The well-immersed cruiser stern allowed for a free flow of water over the propellers, and the propeller shafts were fully enclosed in bossings that were arranged to suit the streamlined flow.

The Ansaldo yards used a new technique of prefabrication in association with electronic welding, with some assemblies weighing in at 27 tons. The hull was divided into eleven watertight compartments by means of transverse watertight bulkheads extending to the main deck, with a collision bulkhead carried to the upper-deck level. The bulkheads were distributed to provide a two-compartment standard of floodability. The hull contained seven decks, the superstructure had four and rose over a hundred feet above the waterline. The Andrea Doria also had a double bottom extending almost the entire 697'2" of the ship.

The power and speed the ship produced was mind-boggling. Her massive twin turbine engines were fired by high-compression steam generated by four main water-tube boilers and two auxiliary boilers. She cranked out 35,000 horsepower and could maintain an average speed of 23 knots for the duration of her Atlantic crossing. In the process, she burned ten to eleven tons of fuel oil an hour.

The Andrea Doria sailed with a complement of officers and crew of 575, a one to three ratio in crew to passengers. Shipbuilders did not like to use the term "unsinkable" since the Titanic disaster 40 years before, but the term, an echo of history, got bandied about nevertheless.

In event of a maritime accident, her Italian builders spared no expense in safety equipment. Twenty lifeboats accommodated over 2,000 passengers, or more than the ship carried. She had 33 fire safety zones. Each one of them could be sealed off in case of a fire within. In an age before they were required, the Andrea Doria had an automatic sprinkler system and a carbon dioxide fire-smothering system. The ship even had its own hook-and-ladder fire fighting company.

As far as creature comforts, the Andrea Doria was without equal. Antiques and modern art by Salvatore Fiume, Luzzatie, and Ratti were evident everywhere. Paintings, murals, mirrors, ceramics, and crystals adorned the walls of the massive ship. The 31 public rooms provided an average of 40 square feet of recreational space for each of the 1,290 passengers that the ship could comfortably accommodate.

For the moneyed elite, the Italia Line provided four unique deluxe First Class staterooms that were designed by Italy's top artist-designers, each consisting of a bedroom, sitting room, powder room, and bath.

As for the rest of the ship, luxury was broken down into three classes, first-class, cabin class ( second class, ) and tourist class ( third class. ) First class could accommodate 207 passengers, cabin class 376, and tourist class 707. All first and cabin class staterooms had private showers and toilets. The entire ship was air-conditioned, and each class had its own dining room, bar, lounge, movie theater, recreational area, and swimming pool. The three swimming pools sat terraced in the stern section of the ship, as one contemporary account described, "in country club settings of tables, sun umbrellas, pool bars, and white-waistcoated waiters." Construction costs for hull and machinery alone reached $30 million, and the art and furnishings equaled that.

Perhaps the most striking thing about the Andrea Doria was not her detail, her machinery, or even her inboard treasures, but the image she struck steaming across the horizon in her full glory. I was a witness to that very vision on more than one occasion. I grew up in the Rockaways, a sandy spit of land extending out from the western end of Long Island. Sitting on the jetty-girded beaches of the Rockaways I witnessed many of the glorious entrances of the proud ocean liners, now long since gone.

The Cunard's Queen Mary, and Queen Elizabeth, the French Ile de France, and the SS United States, and America, all fell under my spellbound view sitting there on the ocean's edge. But it was the Andrea Doria that took my breath away. Her jet-black hull, and the gleaming white superstructure, the rakish single smokestack emblazoned in Italy's colors of green, white, and red made for entrancing a sight as I had ever seen. Those long elegant sweeping lines would forever characterize Italian design for me.

Sitting on that Rockaway beach so many years ago I never dreamed that I would visit that exquisite ship, half-a-lifetime later, in her grave at the bottom of the Atlantic.

( photo courtesy of the Mariner's Museum. )

At 58, Superior Captain Piero Calamai had spent 39 years of his life at sea. A merchant marine cadet, he was awarded the Italian War Cross for military valor during World War I when he was only 18 years old. As a reserve lieutenant commander during World War II, he was awarded again the War Cross for valor. Over his career, he served as an officer aboard 27 ships in the Italian merchant marine before being rewarded with the command of the pride of the Italia Line - the newly launched Andrea Doria.

Captain Calamai was not the gregarious sort. "Dignified but distant" was how his Senior Chief Officer Luigi Oneto described him. He found the social obligations aboard a luxury ocean liner distasteful. A shy, introverted man and a teetotaler, he preferred sharing meals with his officers in their private dining area to the ostentatious soirees in the passenger dining rooms that had become the obligatory duty for any ocean liner master. Ever the proud captain, however, he was always willing to give tours to those interested in the machinations of navigating an immense floating city, from his command center on the bridge.

Calamai was revered by his subordinates. He was always discreet enough to take a man aside and advise him of his mistakes rather than humiliate him in front of his peers. He had the aristocratic demeanor of a polished, concerned, and educated man. His swarthy, sea-weathered countenance was a habitual presence on the bridge of the Andrea Doria, and he rarely took refuge in his comfortable captain's quarters.

After weighing anchor at Genoa on July 17, 1956, the Andrea Doria made three scheduled stops at Cannes, Naples, and Gibraltar. At precisely 12:30 pm Friday, July 20 the Doria bid adieu to Europe with 1,134 passengers and 401 tons of freight. Among the cargo was a very special automobile: the Norseman, an experimental prototype designed and constructed by the Ghia plant in Turin for the Chrysler Corporation. It represented an investment for the Detroit automobile giant of $100,000 and they were anxiously awaiting its arrival stateside.

Captain Calamai piloted his ship on what was called the "Great Circle Route." After skirting the Azores to the northwest, the Andrea Doria steered a course due west for the Nantucket Lightship, the welcoming beacon to the New World.

Captains of ocean liners were always under tremendous pressure to arrive at port on time. Arrival times were carefully calculated with the ship at full speed and any delays meant cost overruns. The additional costs were fuel, meals for passengers, and 200 longshoremen who were hired for the day and who had to be paid. Those were just part of the problem if the ship arrived at dock late. There was also the public relations nightmare of irate passengers late for connections if the ship was delayed in docking. Such were Captain Calamai concerns on the evening of July 25.

One hundred and sixty miles east of the Nantucket Shoals, the Andrea Doria began to run into light patchy fog conditions. Calamai had seen the conditions deteriorate for himself from the exposed bridge wings that extended out from the bridge. The captain knew conditions would worsen once the ship approached the Nantucket Lightship, which was anchored on the southern tip of the shoals. The shoals were infamous for their hazardous fog conditions during July, when the warm, moisture-saturated southwestern breeze blew over the frigid Labrador currents emanating from the North Atlantic. Although Captain Calamai had encountered them before, he was always a worrier. Unlike many other shipmasters, he did not leave fog watch to junior officers. He remained on the bridge.

( photo courtesy of the Mariner's Museum. )

Earlier that day, some 300 miles away, the Swedish-American Liner Stockholm had departed from the 57th Street Pier on the west side of Manhattan at 11:31 am on a hot and muggy summer day. The Stockholm was not in the class of a ship such as the Andrea Doria. Built in 1948, the stark white ship, with its single yellow smokestack, was 525 feet long and her top speed was a respectable 18-19 knots. Her sharply pointed bow was reinforced for following ice breakers, a necessity for the northerly routes she had to take to reach her Nordic destinations.

The Stockholm, a compact ship, was a testament to the frugal ways of the Swedes. She carried only 534 passengers, spread out over her efficiently laid-out seven decks. Her passenger quarters were comfortable but certainly would not be described as luxurious. Because of her unique design - she resembled a very large yacht as opposed to an ocean liner - her cabins for passengers and crew alike all had portals to the sea. The Stockholm had only one indoor swimming pool and just the necessary number of public rooms for her passengers. Overseeing the ship with typical Swedish-American Line efficiency was the austere Captain H. Gunnar Nordenson.

Captain Nordenson, 63 years old and a veteran of 46 years at sea, was a taskmaster. Fraternization between officers and crew was forbidden, as was smoking and coffee drinking while on duty on the bridge. The only words heard in the nerve center of the Stockholm were the orders of the officers and the requisite responses from the crew.

The Stockholm followed the Ile de France down the Hudson River. The 793-foot Ile de France was one of the more storied ocean liners of the century. Though an aging lady of the sea and a behemoth by anyone's standards, the much faster French ocean liner left the Stockholm in her dissipating wake. By the time the Stockholm had reached the Ambrose Lightship, outside of the New York Harbor entrance, the Ile had already disappeared over the horizon. Full speed ahead, the next stop for the Stockholm was Copenhagen, Denmark, then on to her home port of Gothenburg, Sweden.

The Swedish-American line was one of the few transatlantic lines that only required one officer to stand watch while the ship was underway. Most ocean liners had two on duty. The frugal-minded Swedes felt their officers could discharge their duties without redundancy. Seven hours and 130 miles out from Ambrose Lightship, Third Officer Johan-Ernst Carstens-Johannsen relieved Senior Second Officer Lars Enestrom for his four-hour watch.

Seeing to the passengers' needs prior to departure and the loading of cargo and negotiating the tricky narrows of New York Harbor had worn out all the officers aboard the Stockholm. Captain Nordenson had already retired to his quarters for some paperwork but continued to make unannounced visits to the bridge and to check on the ship's heading and scan weather reports.

Carstens-Johannsen, or simply Carstens to his shipmates, had been revived by a few hours of rest, a filling meal, and a steam bath. Before joining the helmsman, lookout, and standby-lookout on the bridge, he had checked out the navigational chart spread in the chartroom just behind the bridge. He also noted the weather forecasts and was not surprised to learn that heavy fog could be expected ahead. Surveying the empty ocean in front of him, Carstens settled into a routine he relished. The tall and robust 26-year old expected his first turn as commander of the Stockholm for the voyage eastward to be uneventful.

Twenty-year-old Ingemar Bjorkman manned the wheel of the Stockholm. In front of him, past the windows of the bridge, was the twilight gloom of the open seas. Bjorkman, who had only three years of sea experience, glanced regularly at the gyrocompass, making sure the course was true to the 90 degrees indicated by the course box which contained three wooden cubes that resembled oversized dice and read "090."

At 9:40 pm Captain Nordenson arrived at the bridge and without ceremony ordered Carstens to change course to 87 degrees. Carstens immediately arranged the wooden cubes to read "087." Bjorkman turned the wheel so the gyroscope headings coincided with the numbers in the course box. Carstens did not question his captain's change of course. He assumed he wanted to cut closer to the Nantucket Lightship before heading east into the open Atlantic.

Approaching the lightship that close was against the 1948 International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea. However, the Swedish-American Line was not a signer of that convention, nor was the Italia Line. The convention would have dictated a course 20 miles further south.

Carstens switched his radar scope's range from 15 to 50 miles. The Stockholm was now plying one of the busiest sea lanes in the world. After a few minutes, with just a few blips on his radar screen, he switched it back to the 15-mile range. He checked the helmsman's gyrocompass, then returned his gaze to the featureless seas in front of him, wondering when they could expect the curtain of fog to fall on them.

Captain Nordenson once again left the bridge, but not before telling Carstens that he was to be notified once the lightship was sighted. Carstens took a reading of the ship's position by dead reckoning. Ascertaining the position of the ship by dead reckoning was a reasonably accurate and common navigational practice aboard ships at the time - LORAN was still new and not totally trusted and GPS (global positioning satellites) unheard of. In dead reckoning, the present position was determined by the distance traveled in relation to the last known position. Carstens calculated that the Stockholm was over two miles north of their desired position due, no doubt, to tidal drift.

The Stockholm was now in a deep fog bank. At 10:04 pm Carstens compensated for the drift north by changing the course to 89 degrees, turning the ship in effect more to the south, or to the right. By this time Peder Larsen had exchanged his lookout post with Bjorkman at the wheel. This was the young Larsen's first voyage aboard the Stockholm. At 10:30 pm, after a position determination from the lightship's radio beacon, Carstens adjusted the ship's course to 91 degrees, since he thought the Stockholm would be approaching the lightship within the two-mile safety range. The Stockholm was now deep in the fog bank. With almost zero visibility, the radar, fog horn, and navigational lights would compensate for the loss of vision. Glancing at his radar scope, still set at the 15-mile range, Carstens noticed a blip on the screen.

Aboard the Andrea Doria Captain Calamai still paced his bridge. The heavy cloud of water particles clinging to the ocean's surface had forced Captain Calamai to order his lookout down from the mast's crow's nest to the bowsprit so he would have a better view of what lay ahead. The fog whistle was set to boom its warning every 100 seconds. From a control panel in the bridge, all eleven watertight compartments were shut.

The speed of the ship was slowed down to 21 knots from 23 knots, not enough of a speed reduction to satisfy the Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea, an internationally recognized agreement. The regulations were somewhat nebulous about the reduction of speed, since it was simply stated that the ship should slow to a "reasonable speed." The general rule of thumb was a ship should slow to a speed where it could stop in half the distance of its visibility. But visibility was virtually nil which meant if the rule-of-thumb were to be followed to the letter the Doria would have to had come to a complete stop. That, of course, was unthinkable. The Andrea Doria was already a projected hour behind its 9 am scheduled arrival. The minimal reduction of speed, nevertheless, was a compromise of safety that would later haunt Captain Calamai.

Fourteen miles west of the Nantucket Lightship, Captain Calamai ordered his helmsman, 59-year old Carlo Domenchini, to follow a course of 261 degrees, which brought them abeam one mile south of the lightship at 10:20 pm. Calamai then changed the course to 268 degrees, on a direct line to the Ambrose Lightship, now only 200 miles away.

At approximately 10:40 pm Second Officer Curzio Franchini noticed a blip on his radar scope. He alerted Captain Calamai of the position of the unknown ship, which was four degrees to starboard and 17 miles away and closing. No officer on the bridge of the Andrea Doria was alarmed, since a single ship in front of them - even a ship on a parallel course - posed no serious threat.

The "Rules of the Road", maritime right-of-way, called for ships on head-on courses to turn right for a port-to-port (left-to-left) passing. Captain Calamai determined there was ample distance between the ships, so he continued on his course, which veered left, or out to open sea. The Andrea Doria's master might have acted differently had he known the ship bearing down on his was a small fishing vessel, as he was led to believe, but another fast-moving ocean liner also intent on keeping to a tight schedule.

Second officer Franchini switched his radar scope from a twenty-mile to a seven-mile radius. Surprised at what he saw, he informed his captain that the ship was bigger and moving faster than they had initially surmised. Still, the second officer projected that they would pass each other a mile apart. Helmsman Domenchini was relieved at the wheel by seaman Giulio Visciano. Calamai then made a critical decision.

Calamai instructed Visciano to turn four more degrees to the left, "and nothing to the right." That meant helmsman Visciano was to execute a slow even turn to the left. Such a maneuver was a fuel-saving and smoother turn, but it was also harder to decipher on radar by another ship.

Informed by officer Franchini that the approaching ship was only two miles away and still on a parallel course, Calamai and Third Officer Eugenio Giannini made their way to the wing bridge to see if they could see the ship or hear its fog whistle. Giannini caught sight of its masthead lights. Moments later, the lower forward masthead light and the aft higher masthead light on the Stockholm appeared to reverse themselves. Adding to his horror Giannini saw the red light affixed to the port side.

The Stockholm was turning directly into the path of the Andrea Doria! Giannini cried out, "She is turning, she is turning. She is showing the red light! She is coming toward us !" Captain Calamai ordered his helmsman a "Tutto sinistre ... all left." Visciano frantically turned the wheel hard left.

Hoping to outrace the oncoming vessel, Calamai opted not to attempt to stop the ship or reduce speed, knowing it would take at least three miles to do so. In a split-second decision, he also decided against the accepted turn toward the oncoming ship, or turning to his right. Such a seemingly dangerous maneuver was considered preferable when collision was imminent: better to chance a bow-to-bow glancing strike than a potentially mortal blow to the ship's flank.

Because of her mass and forward motion, it took half a mile before the Andrea Doria began to respond to the radical course change. The white-knuckled crew on the bridge of the Italian ship watched in horror as the sharply raked bow of the Stockholm appeared out of the fog. All that was left for them to do was to brace themselves. The Stockholm knifed into the Doria, directly under the right wing of the bridge with a sickening, jolting crunch.

( © Harry Trask / Mariner's Museum. )

( © Harry Trask / Mariner's Museum. )

( photo courtesy of the Mariner's Museum. )

Vincenzo Della Torre was relaxing, puffing on a cigarette as he leaned over the ship's port side railing, staring out into the fog. His kitchen duties had ended fifteen minutes earlier. He recalled that night from the comfort of his own restaurant and from forty-three years of hindsight.

"I was thrown by the tremendous impact and ran to the opposite side of the ship where we were hit," he told the New York Times. "Fog was heavy. At first, I saw nothing, but then I could make out the Stockholm's bow stuck deep in our side. People were rushing onto the deck from inside, panicking and screaming in Italian. 'Calmatevi! Calmatevi!' I hollered. 'Be calm!, Be Calm!' I was wearing my white kitchen jacket and they could see I was crew. Most obeyed me. But, to tell the truth, I was just as scared and panicky as they were."

The memories of that night were still vivid 44 years later in the mind of Pat Mastrincola, of West Milford, NJ. The nine-year-old was watching a movie in the tourist class theater that had earlier served as their dining room with his mother. "All of a sudden, the ship made a tremendously hard turn. We all knew something was wrong. The movie screen and projector tumbled over. Dinnerware on shelves behind us avalanched down. The whole audience broke into a panic."

The young boy and his mother scrambled for the exit through crowds of panicked people back to their cabin, at the other end of the ship, where Pat's younger sister was left to sleep. They fought their way through the hordes of frightened passengers to their cabin. Smoke and white powder from the burning insulation ignited by the friction of steel against steel filled the corridors. Amazed, they found the little girl still asleep even though she had been thrown from her bed. Because of the severe list of the ship she had found repose against a tilting cabin wall.

"Eventually, my mom, sister, and I worked our way out to the ship's fantail. Then the ship dipped further, to 25 degrees. B and C decks were completely flooded. That's when terror really set in. Mother, sister, and I clung to the ship's high side. The interior was filled with smoke. Splintered steel and lumber were everywhere. There was nowhere to go. It was foggy and dark. Visibility was zero. There was no sign of help."

Walter G. Carlin, a retired lawyer from Brooklyn, was getting ready for bed in first-class cabin #46 located on the starboard-side upper deck. He had just entered their private bathroom to brush his teeth. His wife was propped up in bed reading a book. The next thing he knew he was sent sprawling to the floor. Staggering back into the stateroom he found his wife, her bed, her night table all gone. In horror, he stared out of the gaping hole where his wife had been, into the black void of night air, fog, and sea.

Several doors down, Thure Peterson, a chiropractor from New York, had been sleeping in his cabin when the Stockholm struck. He had just fallen off to sleep when he was awoken by a "tremendous thud, the sound of ripping steel". Then he saw a mass of white steel brush by him. He felt as if he were flying through space. He then lost consciousness.

Aboard the Stockholm Captain Nordenson with his officers surveyed the damage to his now idle ship. Stunned to wordlessness, they found that 75 feet of the bow had been reduced to a jumble of twisted and broken steel. Ten crewmen had been asleep in their forward quarters. The ones that were not found to be crushed to death in the accordioned bow had been plucked from their bunks and swallowed up by the sea. In the crush, the Stockholm had lost her anchor chains, spilling all 700 feet of the heavy links onto the ocean floor. The anchor winches were obliterated in the collision. Then they made a shocking discovery.

Swedish sailors heard a plaintive voice calling out in a strange language from the wreckage of the bow. They found a young girl wearing tattered pajamas. No one knew who she was, her name nowhere to be found on the passenger roster. Fourteen-year-old Linda Morgan had been traveling with her mother and sister aboard the Andrea Doria!

The teenager had been catapulted by the bow of the Stockholm at impact, and the withdrawing wreckage of the bow had somehow scooped the girl up. She was found some 80 feet from what had been the peak of the bow, huddled behind a sea breaker wall. Her younger sister and mother perished in the collision and their bodies were lost to the sea. The New York tabloids christened Linda Morgan the "Miracle Girl." Under her own power, the Swedish ship eventually limped back to New York with hundreds of survivors from the Andrea Doria.

Although Thure Peterson regained consciousness and managed to free himself from under the debris of what remained of his cabin, forty-three passengers on the "unsinkable" Italian ship did not. With its ice-breaking bow, the Stockholm cut deep into the heart of the Andrea Doria. All seven lower decks had been exposed to the sea in the shape of a "V" below the wheelhouse. The bulkhead deck, or A deck, was where the bulkheads separating the ship into the eleven watertight compartments ended. The steel cap at the A-Deck was suffused with seventeen stairways to accommodate passengers. On a military ship, small hatches could quickly be battened down. But the seventeen cavernous stairways of the Doria became conduits for the rush of water and ruptured oil tanks that spilled down, flooding neighboring watertight compartments on the listing ship. The Andrea Doria had been built to survive the flooding of only two of the eleven watertight compartments.

Hollywood movie star Ruth Roman was dancing in the first-class ballroom on the Belvedere Deck, the very top of the ship. She later told a reporter from the New York Times that without warning, "We heard a big explosion like a firecracker". Seeing smoke, she left the dance floor in her nylon-stocking feet and rushed aft to her cabin, where her three-year-old son Dickie slept. Awakening the little boy, she told him they were "going on a picnic." In the crush of panicked passengers, she got separated from her son. Only when she arrived in New York the next day, exhausted and in a state of maternal hysteria, was she reunited with the boy.

Ruth Roman's escape from the stricken ship was far easier than the poor souls in the cheaper cabins below decks. In the bowels of the ship, passengers in B and C decks had to fight their way up pitch-black narrow staircases filled with their terrified neighbors. Cold seawater, fouled by engine oil, cascaded down the stair and passageways forcing them to pull themselves hand over hand up to the boat deck of the ship, across slippery steel rises. The horrible ordeal took many of them over an hour to complete. On A, B, and C decks, the majority of the forty-three victims perished. Most were poor immigrants dreaming of a new life in America; some were nuns returning from a pilgrimage to Rome.

The last person to leave the Andrea Doria was not the officers and captain as thought on that morning of July 26. That dubious honor went to an American seaman by the name of Robert Hudson.

The 35-year old sailor had been injured in an accident aboard a freighter en route to Europe. He had been taken aboard the Doria at Gibralta and quartered in the ship's hospital for his trip home. Without telling the ship's hospital staff, Hudson had taken a more comfortable bunk abutting the ship's hospital and had fallen into a heavily sedated sleep.

Hudson's slumber was not disturbed by the collision or the pandemonium aboard his comfortable sea-going ambulance. When he awoke early the next morning he was alone on the severely listing ship. Hudson struggled with his debilitating injuries for over an hour to reach the stern.

A lifeboat dispatched by the late-arriving tanker Robert E. Hopkins to search for survivors spotted Hudson. The seamen manning the boat were afraid to approach the sinking ship for fear that if the Doria capsized they would be sucked under with it. Hudson alternated between begging for help and cursing his would-be rescuers for an hour and a half. Finally spurred to action, the lifeboat plucked the injured Hudson from the dying Doria and escaped its suction by some ferocious rowing. It was 7:30 am. The Andrea Doria was now a ghost ship waiting to be received by the ocean bottom.

( photo courtesy of the Mariner's Museum. )

What was later described as a billion-to-one chance accident was the first collision between two ocean liners in history. The rescue of the surviving 1200 passengers and crew from the doomed ship is considered to be the greatest peacetime sea rescue of all times. Besides the Stockholm, four other ships answered the Andrea Doria's distress call. One of those ships was the Ile de France. She raced from her position 44 miles away to help in the heroic rescue mission.

There is still some mystery today as to how these two huge ships managed to collide. The collision would never have occurred had the Swedish-American Line subscribed to the Convention of the Safety of Life at Sea. As William Hoffer said on the collision in his book Saved! : "The Stockholm was, in effect, legally driving in the opposite direction on a wide, but potentially dangerous one-way street. Had they [the Swedish-American Line] followed the 1948 Convention, the Stockholm and the Andrea Doria would have passed each other safely at a distance of twenty miles." After a lengthy litigation in a New York court in 1957, the Italia and Swedish-American Lines agreed to an out-of-court settlement, but the controversy continues to this day.

Some maritime experts blame the Italian captain for excessive speed in less than optimum conditions, and for failing to execute the port-to-port passing. Captain Robert Meurn, a professor at the United States Merchant Marine Academy in Kings Point, New York, takes a different view. Captain Meurn is a recognized authority on the Andrea Doria-Stockholm collision. He teaches a course in Bridge Simulation Training at the Merchant Marine Academy, and he says the Andrea Doria's sinking is a textbook example of what can go wrong when two ships are on a collision course. Meurn is of Swedish descent, and his grandfather taught at the Swedish Merchant Marine Academy. He even remembers meeting the Stockholm's Captain Nordenson as a boy in Sweden. He says he had all the built-in prejudices when he began to examine the accident. Still, he came away with a surprising conclusion: "The majority of the blame I attribute to Carstens-Johannsen."

Meurn has inputted all the data from both ships into the ship's bridge simulator computer at the Merchant Marine Academy. The computer projects images onto a screen and the two ships were put at the distances apart and times that both the Italia and Swedish-American Lines concurred on. Carstens testimony at the inquiry, according to Meurn, did not gibe with the facts.

Meurn explains that Carstens had initially claimed he saw the blip of the Andrea Doria at twelve miles when it was actually only four miles away. In 1956 radar scopes had range scales, which were adjusted by turning a knob. You needed a flashlight to see what scale you were on in a darkened bridge. Carstens, in testimony given at the official inquiry, said he picked up the Andrea Doria on the fourth range ring from the center of the scope. Meurn says Carstens wrongly assumed he was on the fifteen-mile scale where the fourth ring would have indicated the blip was twelve miles away, when in actuality it was on the five-mile scale, making the fourth ring just four miles away.

In accordance with the Rules of the Seas, Carstens testified, he then came about right at 23:05 (11:05 pm) at the supposedly 12-mile mark when he realized the ships were on reciprocal courses. Captain Calamai had the Stockholm correctly plotted from as far away as seventeen miles and rightly assumed if the courses were held the two ships would safely pass each other starboard-to-starboard three-quarters of a mile apart. Still, the Italian captain came left to increase the distance between the two ships.

As to the charge the Andrea Doria did not reduce speed significantly in fog conditions Captain Meurn has only to point to the SS United States. In 1952 the American ship set a transatlantic record with an average speed of 35.59 knots even though the ship was in heavy fog half of the time that she took to cross the Atlantic. Captain Meurn explained: "In those days they all went at full speed through the fog. If they [ocean liners] slowed down every time they encountered fog they [ship captains] would have been relieved of duty. They had schedules to maintain."

Five minutes before the collision, the Stockholm had changed position and came right toward them without signaling with the two sharp blasts of the fog whistle as required. According to Captain Meurn, at that very moment, the Andrea Doria's fate was sealed.

Meurn also believes Carstens was afraid to call the captain when the blip of the Doria was first seen. Meurn describes Nordenson as having an intimidating presence. Carstens, a third officer, should not have been alone on the bridge under such conditions with another ship rapidly approaching it in an opposite direction.

According to Meurn, Carstens "fabricated" his account of seeing the Andrea Doria's red light (on the port side) when he made his last desperate turn to starboard minutes before the violent encounter. The computer simulator proves that the turn was made later, some 30 seconds before impact, much too late to avoid it.

Meurn believes that some good came out of the tragedy. An agreement by all ocean lines shortly after the accident required two officers on the bridge during a watch and VHF radio contact between ships was established.

Hearing of Captain Meurn's conclusions brought a sad smile to the face of Vincenzo Della Torre. As with any tragic mishap or senseless act of violence, there is the term closure for the victims. But for Della Torre there is some satisfaction in knowing the love of his young life was not responsible for her untimely end. Nevertheless, the thought that the sea is now her grave is an unbearably sad thought for the Italian expatriate. He still grieves the loss.

For those of us who love the sea, the loss of human life is tragic but there is no disgrace for an ocean-going vessel to find rest under the waters. Had the Andrea Doria been able to avoid the bow of the Stockholm she would have certainly gone on to serve transatlantic passengers for many more years. They would have been wowed by her structural beauty, her service, her elegance, and her artwork. But eventually, her utility would have come to an ignominious end, as it does for all successful ships. If not for the jet airliner, it would have been age that would have done the grande dame in. Had the whims of fate not interfered, the Andrea Doria would have been stripped of her artistic trappings soon enough and her hull would have been scrapped - the ultimate indignity for any proud ship.

To divers like me the only real tragedy of that night of July 25, 1956, was the loss of those lives aboard the two ships. But the Andrea Doria still lives. It is just that her life goes on many fathoms under the sea where only an intrepid few get the chance to relive her charms.