Brightliner Subway Cars (2/3)

Atlantic City Reef Collapse Yields Lessons

By RICHARD DEGENER, Jul 26, 2009

Press of Atlantic City

ATLANTIC CITY - Evidence suggests the connections are to blame.

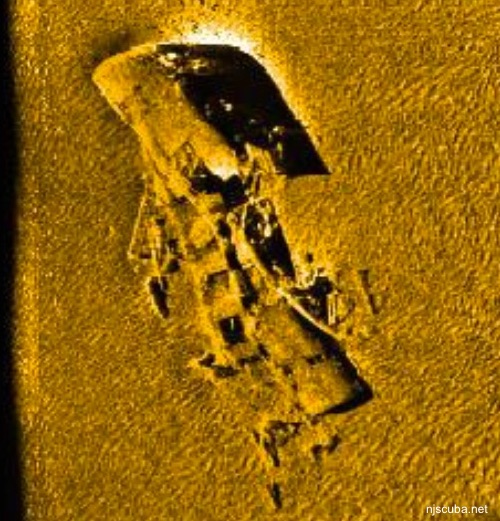

Subway cars deployed at the Atlantic City Reef and other reefs along the East Coast are collapsing into a pile of rubble, after mere months in the water, and it likely is because the connections - such as rivets and spot welding, engineered for subway cars to haul commuters down a track - cannot hold up in a harsh marine environment. Structural framing made of low-alloy steel may also be rusting out, causing the cars to collapse.

It wouldn't be the first time a material hailed by the builders of artificial reefs turned out to only be as strong as its weakest material.

New Jersey and other East Coast states jumped at the offer by the New York Transit Authority for free stainless steel "Brightliner" subway cars as reef material.

Why wouldn't they? Earlier "Redbird" subway cars made of lower alloy carbon steel had been sitting on New Jersey's reefs since 2003 and were holding up well. One study estimated they would be 67 percent structurally intact after 14 years in the ocean. Most figured stainless steel would work even better. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency said the stainless cars should be viable for 25 to 30 years.

New Jersey deployed about 100 of them on reefs off Atlantic City and Cape May and ordered another 500 for three other reefs. South Carolina, Virginia, Delaware, and Maryland also deployed the subway cars off their coasts.

New Jersey gets credit for discovering the problem just seven months after the first cars were deployed in April 2008 and canceling the order for 500 more cars. That led other states to check their reefs, and they found the same problem.

"It's how the components of the cars are connected to each other. The rivets and spot welding are the weak link. The stainless steel skin peels right off," said Daniel Sheehy of Aquabio, a Massachusetts firm that for 30 years has evaluated reefs around the world.

It may take a metallurgist to confirm the problem Sheehy has seen while reviewing underwater video and side-scan sonar reports, but Sheehy said, "It's a common problem with reef programs. People look at the materials and forget the materials are attached to other parts. We need to capture these lessons and learn to get smarter about these things."

The most famous case was the Osborne Reef off Broward County, Fla. where 2 million bundled tires were dumped in the 1970s. The tires were banded together with steel, which rusted out and left 2 million tires to wash ashore in storms, battering ecologically sensitive coral reefs. The military is now helping to recover the tires.

Tire reefs on the Great Lakes and Puget Sound failed for similar regions. Even though New Jersey anchored its tires in concrete, it stopped using them as reef material upon the realization that the concrete would fall apart before the tires.

Information about the subway cars may have been available before they were used as reefs. Sheehy noted the petroleum industry, which often works in the marine environment, has documented problems dealing with stainless steel. Some grades of the metal are not suited for the marine environment, and connections can be difficult.

"People think stainless steel will last forever. The best reef materials pose difficult questions and lots of intangibles," noted Sheehy.

A few years ago, Army tanks were the reef material of choice. Nothing is as durable as a tank, right? But Sheehy said Maryland deployed them in muddy bottom, and they sank right out of sight.

While tanks deployed off New Jersey have been pretty stable on the state's sandy seafloor, it points to another issue. The best reef materials can be put in the wrong place. The wrong place can involve the makeup of the ocean floor, currents, or other marine conditions. Even ships have been known to break up due to strong currents.

"This happened off Florida where pieces of a ship dragged across coral and damaged it. They use to blow ships up to sink them until they found out it destroyed their structural integrity," said Sheehy.

Retired reef expert Bill Figley, who ran New Jersey's reef program for decades, said one problem is reef builders don't always get the ideal sites due to considerations such as commercial fishing grounds.

"It's not always the best spot but the best acceptable spot," said Figley.

Currents can be a problem at some of the state's 15 reefs. Figley also noted that, eventually, everything breaks up or sinks into the sand. One ship the state deployed has descended 25 feet into the ocean floor.

"Everything eventually goes down. There's a constant battle with gravity. In a storm, the sand liquefies and it won't hold anything up," Figley noted.

One rule Figley always followed is that the component parts of any reef addition must be stable on their own. He noted New Jersey mostly uses rocks these days; and as they sink, more can be piled on top. Lessons have been learned.

"Concrete, steel, and rock is what New Jersey has learned. No plastic, no lightweight stuff, no rubber, and no wood. Ninety-five percent of what we use now is bedrock, natural bedrock," Figley said.

The beauty of rock is that it doesn't just attract fish. One debate on artificial reefs is whether they merely attract marine life already in the area or create it. Rock piles are known for growing marine biomass on the lower end of the food chain, and their many crevices serve as hiding places for juvenile marine life. They may create more than attract.

One thing is clear, reef builders are still learning.

"In the old days, it was just pitching tires overboard. There's been a lot of progress," Sheehy said.

The lack of marine growth shows just how quickly these cars disintegrated.

Even in this collapsed state, the Brightliners continued to support fish and marine life, as evidenced by fishing reports, although the low relief of a collapsed car offers just a fraction of the hoped-for benefit. Also, such low-lying rubble will soon disappear into the bottom. The big problem though was jagged sheets of stainless steel drifting for miles around, and damaging commercial trawlers' nets.