Identifying The Emerald

New Jersey scuba divers provide evidence of the identity of a popular New Jersey dive site

By Capt. Steve Nagiewicz

Additional Research by Jeffrey Bonnell

Photography by Capt. Steve Nagiewicz, Rich Galiano,

Perry Arts and Harry Roecker

IT HAS BEEN ESTIMATED by many shipwreck sources, that well over two thousand ships lie wrecked along the New Jersey shore. What may be surprising is that these many thousand shipwrecks are mostly un-identified. The shipwreck has long since become a historical footnote or dusty file buried among old boxes in a forgotten corner of an archive room. Their tragedies had been recorded through shipping records, harbor master logs, and insurance reports. Most of these records reside in maritime libraries, museums, historical societies, and even newspaper archives. Most were common, historically insignificant ships. Their comings and goings are of no real interest to anyone except to shipping agents expecting delivery of cargoes or families awaiting the arrival or watching the departure of loved ones. While many of these shipwreck locations are known, for the most part, their true identity remains a mystery.

Herein lies the game, a puzzle if you will, of trying to match artifacts found while scuba diving the old decaying bones of a shipwreck against the records and histories tucked away in some forgotten corner of history in order to place a name upon the old shipwreck. We become detectives in a sense, piecing together many odd and different clues to find a "suspect" and hopefully "convict" our shipwreck. We are looking for a chance to put a name on a wreck, something very few people are able to do. This is the story of one such quest; to identify the wreck of the Emerald Wreck.

Background

The Emerald Wreck is located about 11 miles south of Manasquan Inlet. It is a very small wreck, relatively undistinguished as shipwrecks go. It was once a small coastal steamship, a freighter built to carry cargo to ports along the coastline. She was a wooden-hulled ship, average in almost every sense of the word. The age of the wreckage indicates she was sunk many years ago as can be evidenced by the rotted wood timbers of her hull and rusted iron and steel machinery.

Six years ago several divers started working the wreck in earnest, digging throughout her wreckage looking for artifacts with the idea of trying to find out her true identity. There are several possible stories for how the Emerald first got her name. One account has it that the green glass hue from the many ginger ale bottles found on the wreck lent the name. Another says that early salvage divers were salvaging the brass valves and pipes which had that emerald color or green patina which is very often found on corroded brass and copper. What we will discuss next are our processes that we followed to identify the true name for a shipwreck nick-named the Emerald.

Learning the Shipwreck

A diver's first glimpse of the underwater wreckage (see Figure 1) of the Emerald would be the two large steam engines that stand about 15 feet tall and loom over the remains of the two smashed and flattened steam boilers and bits of wood hull and machinery lying alongside this main wreckage. As you swim forward of the engines and over the boilers, the wreckage thins out, abruptly disappearing into the sandy seafloor. The entire wreckage area covers less than 90 feet. Almost all of what is left of the ship lies buried under three feet or more of sand. The sand itself is like sugar in a bowl, if you scoop a spoonful out of the sugar jar, you can see the remaining sugar slide down into the hole made by your spoon. It is very much the same underwater, as you dig a hole using your hands, a scooter or dredge, you can watch in exasperation as the sand grains quickly slide down the slope of the hole and immediately fill it back in. Any hole we dig is just as quickly covered over by cascading granules of sand maddeningly making most of the work we do impossible from the start.

In order to learn the wreck, we decide that we must make many dives to see what it is we are looking at. Not only has the condition of the wreck fallen apart over the ravages of time and actions of a relentless sea, but the metal, wooden hull, and other parts of the ship have been covered by a living blanket of marine life which has obscured the once recognizable ship. This living blanket is problematic for us. The growth will overgrow the wreck and obscure parts of the wreck which might cover a feature we can use to help put a name to this wreck. The growth covers perhaps a builders plaque, which is a metal plate usually affixed to the engine or similar permanently mounted heavy steel machinery and found on just about every ship ever built, which would have included the date, shipyard, and original name of the newly built ship. This builder's plaque would be an ideal way to name the wreck. So too, would be it be fortuitous for us to find some cargo or ships tools or machinery which has a serial number or ship name embossed.

an Emerald Wreck engine

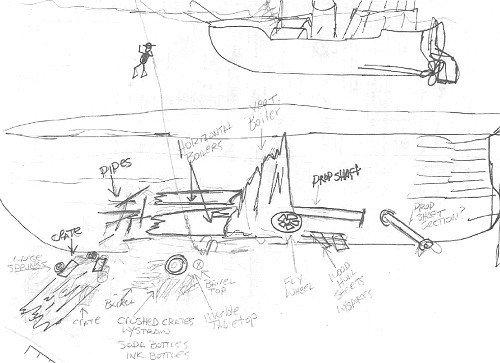

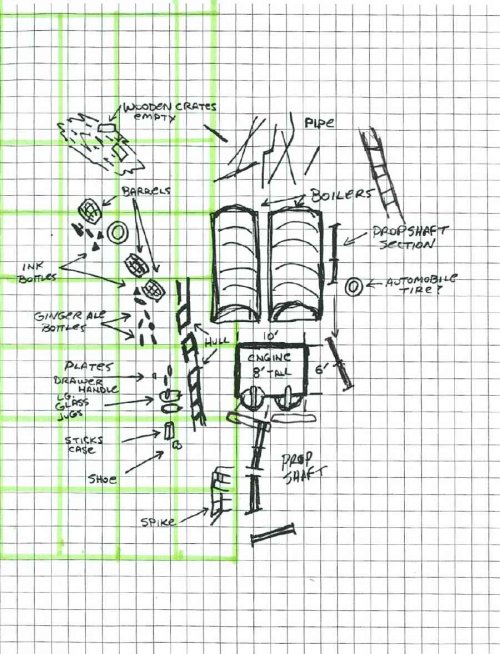

Thus our first step will be to tour the wreck, take an inventory of what we see, and start assembling the images of what is left (see Figure 2). We find, for example, during our many dives a propeller and part of its shaft over 100 feet off the wreck. A clue perhaps? Why is it out here away from the main wreckage? Was it dragged here by some outside source? Many questions, few answers. About 75 feet forward of the boilers we discover a deck winch, indicating we found the bow. In-between we find evidence of low-lying wreckage, some hull, others we were not sure. Like parts of wreckage looking like large spring coils of similar size and design to what you would see on the chassis of a large truck. The wreck is old enough to have been built and sailed long before automobiles. So what are these? This re-construction will help us find out where the cargo holds might be, where the bow is and how the wreck lies embedded into the seafloor and where hopefully we will find potential wreck identifying artifacts.

Developing a Search and Site Plan

Our situational dives told us that in order to find what we were looking for; we need to look at this project just as any underwater archaeologist would. With that in mind, we needed to take measurements of the wreckage. We start to develop a site map and draw out as best we could at depths of 80 feet, often in cold water and poor underwater visibility. This would enable us to figure out how the ship lies. We judged that the bow must have hit first as the wreck sank and buried itself into the soft sand. That hit caused the ship to buckle and we think bend to port somewhat so the sides or hull split and fell outward, essentially laying bare the middle of the ship (see Figure 3). Over time the shifting sands, waves, and storms buried over the wreckage. The wood boring organisms did what they do best, eat through wood timbers. Seawater is a mildly corrosive substance especially when it has a chance to work over long periods of time. It reacts with materials, especially metals, to rust steel and corrode machinery into hardly recognizable lumps of metal.

boilers of the Emerald

With basic measurements, we could now construct the outlines of the wreck and start the process of thinking of her as she once was: a steamship. The other advantage is these measurements would allow us to dig in specific locations and track our progress. A hole dug on one trip would be filled in by the time we returned a week later. Knowing specifically where we previously dug holes would ensure that we would not waste time digging holes in the same spot (see Figure 4).

Searching the Shipwreck

In addition to mapping and wreck orientation, we need to understand how ships were constructed, so as we swim over wreckage we can visualize how it might have looked. Steamships have a particular style and many variations among size and type. It is important that we learn where the galley might be, or her cargo holds, so items we potentially recover might contain a clue to the ship's name. Since the boilers of the wreck are so demolished, we cannot expect much there. So too with the twin steam engines. They are so corroded and covered with Marine life, we feel that by attempting to de-nude this part of the wreck would take too much effort, and most importantly it would destroy habitat for local marine life, something that would be wrong to attempt.

Since we have probably identified the general layout of the wreckage area, we decide to dig in the areas that might represent the galley and main cargo holds. We felt that as we dig we might stumble over (or luck into) the wheelhouse and her identifying artifacts. We also felt that given ever-changing dive conditions, we can alter our plan to dig in places close to the main wreckage when visibility conditions forced us to stay closer to the wreck.

Our plan was to start work about 20 feet ahead of the boilers and 20 to 35 degrees off each boiler so that we were going to cover a swath from port to starboard that measures 75 feet by 10 feet fore to aft - a 750 square foot area. The distance we would cover would be 75 feet across. We expected to dig down two or three feet, but often we found ourselves 5 to 6 feet beneath the seafloor, looking for artifacts. Thus our 76-foot dive would sometimes change into a 82-foot profile mid-dive, a factor we had to consider for gas planning on dives.

Having the Proper Tools

Performing any type of underwater survey, wreck salvage, and artifact recovery would require specialized tools. Initially, we used hand-fanning and ping-pong paddles which were ideal to save divers' hands from the stresses of digging. After a while, we switched to DPV's (Diver Propulsion Vehicle) or a scooter. This device was designed to tow divers who would grab the handles and use the scooter to tour a wreck or reef. By flipping the scooter 180 degrees we used the propeller of the scooter as a motorized fan. It would blow away the sand and dig into the sandy sea bottom. The problem was that the scooter was not designed for this and its thrust was always pushing us backward at two knots. We were constantly tired from the effort and looking for some piece of firm wreck to hang onto. If you dived alone, you had to hold a dive light to see what you were digging into and hold onto the scooter. It was very strenuous work at best (see Figure 5).

It was Enrique Alvarez and the Sea Lion who started using a water dredge to make the work less strenuous and improve the scope of the work and the speed. The water dredge works on the Bernoulli Principle which simply stated injects water flow into a tube and forces the water to jet down and turn back onto itself creating a vacuum effect. This underwater vacuum uses water pumped down from the surface by a water pump down a two or three-inch fire hose. The gun part of the dredge is about 3-6 feet long. The vacuum sucks up sand and material into the length of the tube and out the back end.

Finding Artifacts

As we developed wreck site plans and our digging goals we and several other dive boats and divers recovered hundreds of different artifacts, sometimes by the case lot. We found so much of her cargo that we did not know what to do with all the stuff, but nothing that was out of the ordinary to prove her name. What we did find was several artifacts pictured here that narrowed our search time period down by the years during which they were manufactured, their port of origin, and what they were. The earliest artifacts we found were bottles, lots of them. Then we started finding unique things, like children's items. The glass shoes (see Figure 6) for example, usually contained flavored and colored sugar water. The jewelry (see Figure 7a and 7b) was semiprecious beads and stones. The water bottles helped point to the port the ship probably sailed from. The Congress & Empire Spring Water bottles were made and filled in Saratoga, New York (see figures 8, 9, and 10).

Figure 6 Sampling of some of the artifacts recovered over the years. The small glass shoe was one unique artifact we hoped would give us some clue to her name and origin. It was actually manufactured for a short period of time during the 1850s to 1870s. So it helped in a way to narrow the time period.

Rounded bottom, blob top. Hundreds of these were cargo. Capt. Paul Hepler estimates there are 14 or so different types of bottles with different coloring, wording, or sizes. One bottle is from the Cantrell & Cochran Company, now known as C&C cola.

Researching Information and Then Making Assumptions and Proving Your Thesis

As odd as this will seem, we kind of knew what the wreck's name might be. We did a large amount of research during this time trying to get information, not only on the Emerald but for dozens of other wrecks in which we were interested. The transit of vessels all during this time period was recorded in any number of official records. The wrecking of these vessels was often written up in local and national newspapers and quarterlies. There, for anyone who cared, were the names of several possible candidates for the Emerald. We only had to match up the circumstances to find our best choice. But therein lies the rub. While we could make an educated guess with some certainty, we could not prove without a shadow of a doubt that this was indeed the ship we sought.

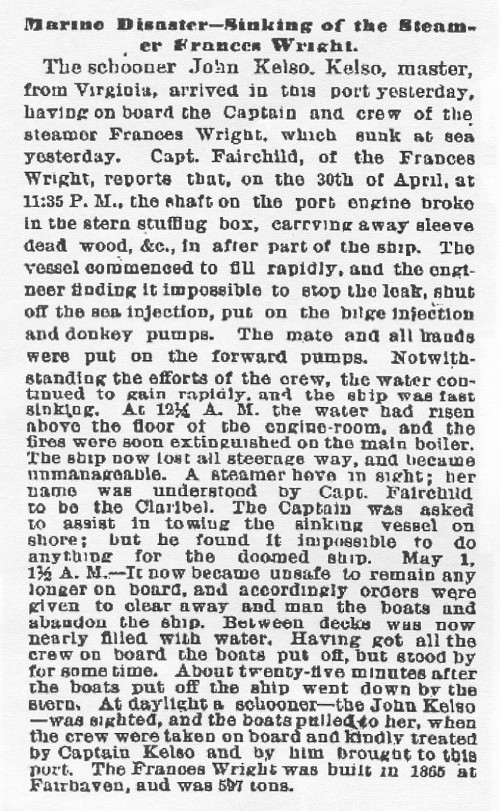

We figured our wreck was the FRANCES WRIGHT. There in the New York Times (see Figure 11) was the story of her sinking. Included was the place, date, and time. Here we had everything we needed. We just did not have the provenance or the proof that this was indeed the ship. Five years of regularly diving the wreck was what it took to gather enough information, process hundreds of clues and research each artifact.

Jeff Bonnell went even further than many of us thought. He visited a fortune-teller. This person took him back to the time where he was a passenger aboard the ill-fated ship (so she claimed anyway). Yes, we did get a bit frustrated and even desperate to lay claim to her true name. Then I found the wood barrel top (see Figure 12). There it listed the year the fish barrel was processed and placed onboard for shipment - 1872. This finally made sense. The packaged fish would not have been processed long before the shipping date.

So let's re-cap. We knew the wreck was 11 miles or so from Barnegat Light in 80 feet of water. The wreck that lays on the seafloor has two small steam engines and has a broken port propeller shaft (see Figure 13). The rest of the shaft and port propeller lay a short distance away from the site. The FRANCES WRIGHT sank after her port propeller shaft broke and fell out of the vessel, thereby creating a large hole for the sea to enter.

Of the many artifacts we recovered, we managed to narrow the wreck's age to a 20 year time period of 1860-1870s. Some artifacts had small Navy anchors, others were only manufactured during this time period. By assembling each clue we could piece together a rough outline of the wreck, but the cornerstone was the top from a fish barrel that put the date to the sinking the thereby narrowing our list of candidates to the FRANCES WRIGHT. The FRANCES WRIGHT sank early on the morning of May 1st, 1873, about 11 miles southeast of the Manasquan inlet.

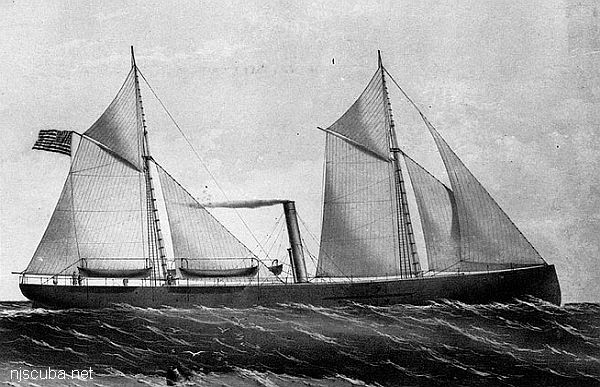

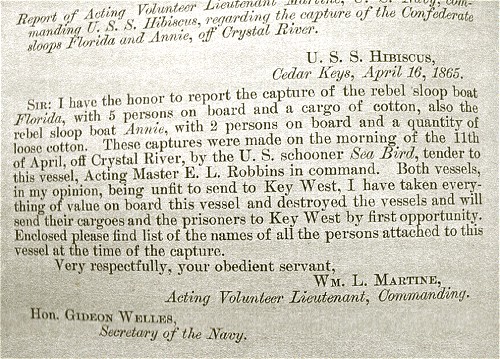

Further research provided the ship's first name, the one which she was initially built under the HIBISCUS. She was built in 1864 at Fairhaven, Connecticut as a wood-hulled steamship, powered by coal-fired twin steam engines with a gross tonnage of 597 and was built to a length of 161ft with a 31 ft beam. She drew 9ft of water. The FRANCES WRIGHT, ex. HIBISCUS was smallish even by the time periods standards, but she plied the coastal trade after steady but reasonably un-eventful service for the Union Navy (see Figure 14).

Armed with this information, we could now trace the brief maritime history of a relatively unknown and insignificant steamship. While we did get to put a real name on her, she will likely always be the EMERALD to divers and especially every diver who helped dig the wreck over the years.

The break is visible at the top of the photograph.

References

Publications & Books

- Americas Maritime Heritage. Eloise Engle & Arnold S. Lott. 1975.

Naval Institute Press - American Merchant Ships 1850-1900 Frederick C. Matthews. 1930-31.

Marine Research Society - Encyclopedia of American Shipwrecks. Bruce D. Berman. 1972.

The Mariners Press - History of American Steam Navigation. John H. Morrisson. 1958.

Stephen Daye Press - Lists of Merchant Steam Vessels of the United States.

The Lytle-Hold-Camper Lists Steamship Historical Society - Maritime New York in 19th Century Photographs, Harry Johnson & Fredrick S. Lightfoot. 1980. Dover Press

- Official Records of the Union & Confederate Navies War of the Rebellion

- Perils of the Port of New York, Jeannette Edwards Rattray. 1973. Dodd,

Mead Books - Shipwrecks off the New Jersey Coast. 1965.

Walter & Richard Krotee - Archaeology Beneath the Sea. George Bass. 1975.

Walker & Company - Nautical Archaeology. Bill ST. John Wilkes. 1971.

Stein & Day - The Underwater Dig. Robert Marx. 1975.

Gulf Publishing

Museums, Historical Societies, and Archives

- Atlantic Mutual Insurance Research Library

- Lloyds Lists 1865 - 1875

- National Archives, Washington, DC

- NJ Historical Divers Research Library

- New York Public Library

- New York Times Archives, New York, NY

- Mariners Museum of Newport News, VA

- Ocean County Historical Society, Toms River, NJ

- South Street Seaport Museum

- Steamship Historical Society and Steamboat Inspection Records

- United States Coast Guard

Reprinted From:

NJHDA JOURNAL

Vol, 6 No. 3

September 2004