Searching For Shipwrecks

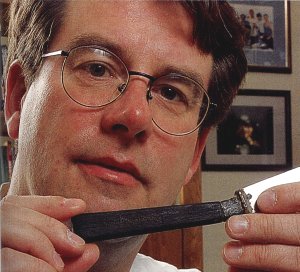

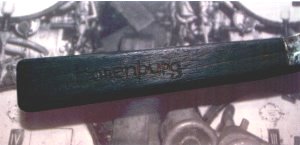

knife, the most tangible clue to the

identity of New Jersey's mystery U-boat.

In 1991, while checking out an obscure site known for hanging up fishing lines, I dropped down the anchor line only to find a virgin German U-boat. A wreck diver's fantasy of discovering a new shipwreck somehow had become a reality, and it was every bit as good as could be imagined. While reveling in the experience, I wondered if I would have enough skill and luck to ever make it happen again. Several discoveries later, the challenge is still irresistible.

by John Chatterton

To be successful at searching for a shipwreck, you must be a creative historical researcher, a precise navigator, and a well-prepared diver. Rely more on planning and less on luck. If you are not willing to be more dedicated than everyone else, then it is pretty much certain you will not dive the wreck until after someone else does.

The Historical Research

Original research is conducted on original documents, without relying on another researcher's interpretation for content and meaning. Although you should be aware of what others have published, original research is where it's at. Locating and interpreting original documents offers a chance to be creative and ingenious.

Getting all of the basic data about the ship is essential, so you can communicate effectively with people who are in a position to help you. You will need to know the dimensions, builder, owners, previous names, and type of vessel.

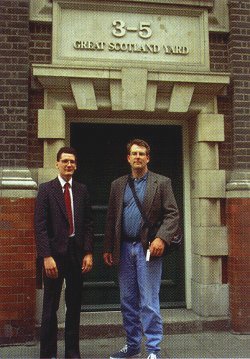

doing U-boat research in London.

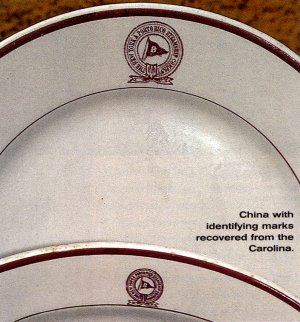

The best sources for data on modern merchant vessels are the American Bureau of Shipping Registry and the Lloyd's Register of Shipping. The ABS tracks American-owned vessels, while Lloyd's tracks foreign-owned vessels. These annual publications list all vessels sailing for any year. Although generally quite accurate, they sometimes contain errors that are repeatedly reproduced. For example, the 1918 ABS, and several popular wreck books, list the S.S. Carolina as being a twin-screw ship. In fact, the S.S. Carolina underwent a major reconstruction in 1914 in which the entire stern was rebuilt and the ship was changed from twin to single screw. This information, although published in several marine engineering journals at the time, was never updated in the ABS.

If the ABS or Lloyd's registries can be in error, then what about newspaper articles or eyewitness accounts? Some popular dive and fishing guides also incorporate data on their ships' histories. Distinguishing accurate from inaccurate information will determine the success or failure of any research project. You might think of yourself as a detective ferreting out the truth.

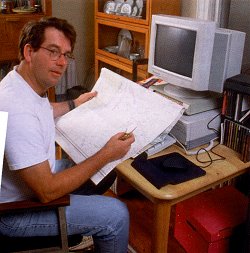

John Chatterton searches for clues to wreck sites in his research office.

Original research is conducted on original documents, without relying on another researcher's interpretation for content and meaning. Locating and interpreting original documents offers a chance to be creative and ingenious.

Learning basic information helps in gaining additional knowledge about a wreck, such as determining the circumstances of its sinking. A good book or article can identify some information resources and point to others. Review books on similar subjects to find potential resources that were used by other researchers, but missed by those who have researched your subject. Make an organized list of sources to investigate.

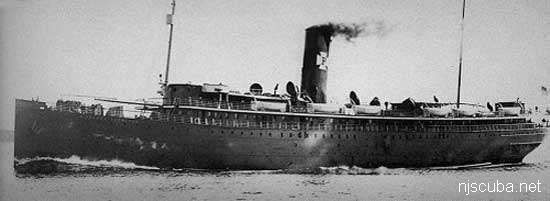

The S.S. Carolina

| Type of vessel: | Passenger freighter owned by the New York and Porto Rico Steamship Co. |

| Official Weight: | 4,515 metric tons 5,017 U.S. tons |

| Date of sinking: | June 2, 1918 |

| Cause of sinking: | Sunk by gunfire from the U-151 |

| Max Depth of dive: | 75 meters / 244 feet |

| Location: | 60 miles east of Atlantic City, NJ, USA |

On what would later be called "Black Sunday, " the German submarine U-151 sank six ships in a single day, June 2, 1918. Of the three sailing vessels and the three steamers, the Carolina was indeed the prize. The Carolina was approached by the U-151 on the surface, and she was ordered to abandon ship. The 218 passengers and 117 crew took to the lifeboats and headed for shore, some 60 miles away. Then the U-151 shelled and sank the abandoned liner. Three women, nine men, and a boy became the first casualties of the U-boat war in America when their lifeboat capsized during the night.

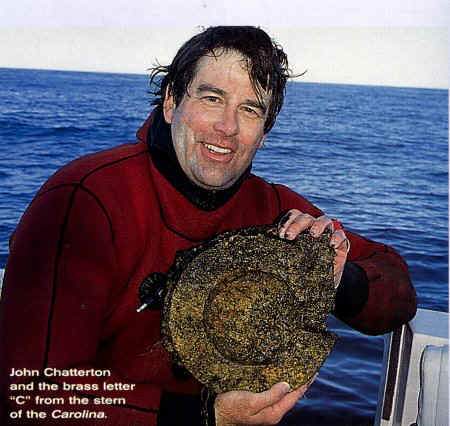

Captain Paul Regula, captain of the fishing charter vessel Bounty Hunter, and I compared my historical data with his hang numbers. In June 1995, he took a boatload of divers to what was believed to be the wreck of the Carolina. On the second dive, I found the brass letters "CAROLINA, NEW YORK" on the stern, and returned to the surface with the letter "C".

On Nov. 2, 1995, I was made the custodian of the wreck after filing admiralty arrest papers.

Most museums or archives insist upon written requests for documents or records, but a wealth of information can be obtained by just talking with the archivists. They are key to your gaining information, so the better you can explain exactly what you want, the easier it will be for them to help you. Nothing is more valuable than an archivist with a genuine interest in your project. Try to form relationships that will be useful for future projects.

Broaden your research beyond archives, museums, and traditional sources of original documents. Make use of electronic resources such as the telephone, facsimile machine, or the Internet. When getting information by telephone, have all research data readily available and be prepared to take further notes. Always be patient and polite. An archivist who thinks you are knowledgeable, organized, and courteous is much more likely to provide a good tip.

Warships, of course, will necessitate the use of government archives and an increased awareness of the legalities of diving and salvage. Admiralty law has some unique provisions for warships. Consulting with a legal specialist might be in order before commencing dive operations.

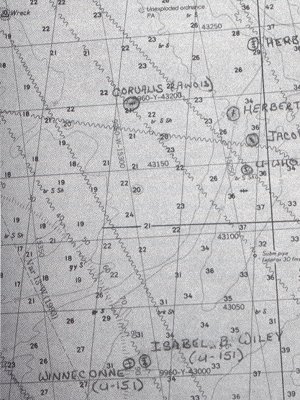

Navigation and Plotting

While compiling historical information, you should seek navigation and positioning data relative to the sinking. An understanding of the basics of navigation and chart reading is essential to put this information into context. Most people know little about navigation, so they will talk about wrecks hundreds of miles away as if they were next door because they don't fully understand latitude and longitude. Know your navigation.

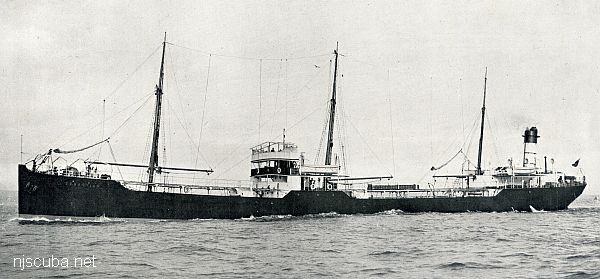

The Norness

| Type of vessel: | Panamanian-owned, German-built oil tanker |

| Official Weight: | 8,619 metric tons 9,577 U.S. tons |

| Date of sinking: | Jan. 14, 1942 |

| Cause of sinking: | Torpedoed by U-123 |

| Max Depth of dive: | 87 meters / 284 feet |

| Location: | 60 miles south of Montauk, NY, USA |

The Norness was the first World War II casualty of the U-boat war on the U.S. side of the Atlantic. She was sent to the bottom by Captain Hardegen of the U-123 with three torpedoes that signaled the beginning of "Paukenschlag" - Operation Drumbeat - the German U-boat offensive against shipping in and around the U.S.

All necessary historical data was compared with information on fishing hangs supplied by numerous sources. In August 1993, while diving from the SEEKER, examined a set of numbers that were received from wreck diving explorer, photographer, and author Brad Sheard. Although the site seemed certainly to be that of the stern of the Norness, positive identification was not made until July 1994, when the wreck fielded a white ceramic with "NORNESS" written across the top in bold letters.

The bow section has yet to be found.

It also is important to know about your targeted dive site. If you don't, then find someone who does. While researching the S.S. Carolina, I was fortunate to hook up with Captain Paul Regula, who runs the fishing charter boat Bounty Hunter. He was not only knowledgeable about the waters but had an interest in the Carolina as well. Between my research and Paul's awareness of local fishing hangs, we were able to figure out the sites of all six of the Black Sunday wrecks, including the Carolina ( see S.S. Carolina specs ), in one afternoon without leaving the dock.

As you collect navigational data, plot it on a chart. In the United States, standard non-laminated paper charts from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration probably are best suited for this work. Plot everything that may be relevant, such as vessel headings, tracks, or other known wrecks in the area. Chart everything in pencil - never use ink - then invest in a good eraser.

Some dive guides have wreck locations included, plus there are numerous commercial wreck number books available. Wrecks and obstructions in the United States are plotted in the Automated Wreck and Obstruction Identification System of the U.S. National Ocean Service. The NOS can provide this data via mail or the Internet, but the numbers are of dubious value. There's no reason to believe that anyone has ever checked any of these locations. However, if you sift through enough rocks, you might find a rare gem. Unknown fishing hang numbers recommended by friends can lead to some adventurous diving, although the odds are against a big score.

into the wooden handle of a dinner

knife ( also known as the Horenburg knife )

remains one of the only clues to

the identification of the U-Who.

Should you find an interesting wreck, the research process works in reverse. All the information must match the historical records. Everything that is important in researching a particular ship is just as important when trying to research the identity of a wreck in this way.

Electronic detection equipment can help to identify promising sites. Proton magnetometers are not all that expensive and are good for working relatively fast search patterns. Of course, they yield little information about what might be found other than the size of the magnetic anomaly, so they are best at locating wrecks that are mostly ferrous metal.

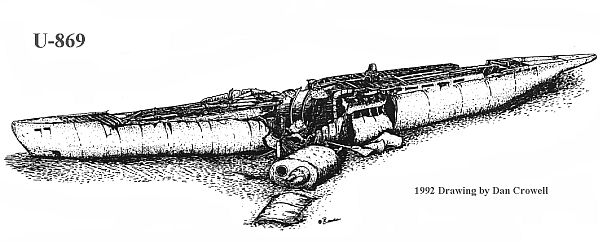

U-Who ( U-869 )

| Type of vessel: | Type IX-c/40 Modified German U-boat |

| Official Weight: | 1,131 metric tons 1,257 U.S. tons |

| Date of sinking: | Unknown - sometime after April 15, 1944 |

| Cause of sinking: | Unknown |

| Max Depth of dive: | 70 meters / 229 feet |

| Location: | 60 miles east of Point Pleasant, NJ, USA |

In September 1991, the late Captain Bill Nagle of the SEEKER took a boatload of deep divers to a set of hang numbers 60 miles offshore. Much to our surprise, it turned out to be a German World War II U-boat, but which one?

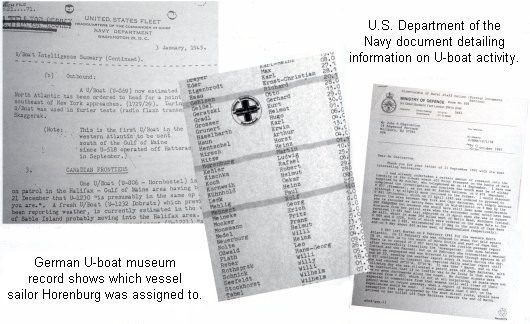

Deep diving explorers and buddies John Yurga and Barb Lander have helped in the extensive research, which has included trips to Germany and England. The current theory is that it is the wreck of the U-869, erroneously reported as being sunk off Gibraltar. A dinner knife with "HORENBURG" carved in its wooden handle was brought to the surface in November 1991. The only sailor in the U-boat service with the last name of Horenburg was radioman Martin Horenburg, who was lost on the U-869. The U-869 might have been sunk by one of her own T-5 acoustic torpedoes on a circular run. This identification still needs to be confirmed with additional artifacts, so the research continues.

Sidescan sonar is a more costly solution, with units starting at about US $25,000. Sidescan gives a more visual idea of what is on the bottom and how it is arranged. In some cases, it has reportedly "seen" wrecks covered in silt. Aside from the cost, another disadvantage is that the side-scan is an extremely slow way to cover large area searches. Sidescan sonar requires good weather and a responsive vessel. This is true to a lesser extent with the magnetometer as well.

Diving the Wreck

Whether you have your own dive boat or charter one, the craft must be suitable for both the destination and the number of people who will be needed for the trip. If you charter a boat, the captain should have a clear understanding of how you wish to conduct the business. Prepare contingency plans for every possible situation. What will you do if you cannot find the target, or if there is bad weather, or what if a diver is injured?

Make certain that only competent divers are on the boat. An exploration trip is not a place for diving instruction. Take only people you know or those who come highly recommended by mutual dive buddies. Not all divers are interested in joining a search, especially if it means that they do not get to dive that day. Make certain that all members of the team know their roles and are aware of all costs ahead of time. This might keep you from losing some of your diving friends. The demands of exploration diving are far greater than those of conventional recreational diving for several reasons. First, you are likely to be the first diver to experience the conditions one the wreck. What if fishing nets await you? In addition, the wrecks tend to be deeper and in more remote locations, so fitness, equipment, and preparation take on increased importance. There may be advantages to using Nitrox or mixed gas, which have additional responsibilities associated with their use.

The Sebastian

| Type of vessel: | British oil tanker |

| Official Weight: | 1,661 metric tons 1,846 U.S. tons |

| Date of sinking: | May 9, 1917 |

| Cause of sinking: | Overwhelmed by gale and fire |

| Max Depth of dive: | 70 meters / 229 feet |

| Location: | 90 miles southeast of Montauk, NY, USA |

Captain Dan Crowell of the SEEKER and I received numbers from a fisherman, who believed them to be the site of a very big wreck. In July 1995, we stopped there after a disappointing dive on the Pan Pennsylvania, a World War II wreck. We were surprised to find an upright, amazingly intact, World War I era tanker. On his first dive on the wreck, underwater explorer and author Gary Gentile found the ship's bell identifying it as the Sebastian.

The Sebastian was disabled by a furious fire astern. Several vessels came to her aid but the weather had turned most foul. U.S. Naval vessels attempted to tow the Sebastian to shore, but she began to lay low in the heavy seas and she went down. All but one of the crew was saved.

If locating the wreck is half the job, then being able to positively identify it is the other half. Study what has been used to identify other similar wrecks. Do not just go down to wander aimlessly around the wreck looking for something to identify it. Be specific: "I am going to look for one of the capstan covers. Photographs and drawings of the ship's bow show that two capstans are located there." the more specific the plan, the better the chance for success. When looking for the bell, capstans, or whatever, know where they were and what they looked like on the ship. Review photos or builders' plans of the part of the wreck you plan to search. Rely more on planning and less on luck.

Last Word

If you are going to be successful at searching for shipwrecks either you are going to have to be very, very lucky, or rely on teamwork and then still be lucky. From archivists to mariners, to boat captains to experienced wreck divers, the more talented people you can involve in a project, the better the chances for success, and the more fun it will be.

There are critics who seem to think that wreck diving, especially deep and technical wreck diving, has too many inherent risks, and that deep technical dives would be better done with saturation systems, NEWTSUITs, and remotely operated vehicles. It is true that there are significant risks involved, and these risks need to be managed by anyone who chooses to participate. There is a personal challenge in rolling over the side with a gas supply on your back, and swimming free into the dark unknown. Besides, few can afford any of that other stuff.