Teredo (Shipworm)

Teredo navalis

Size: to 5 "

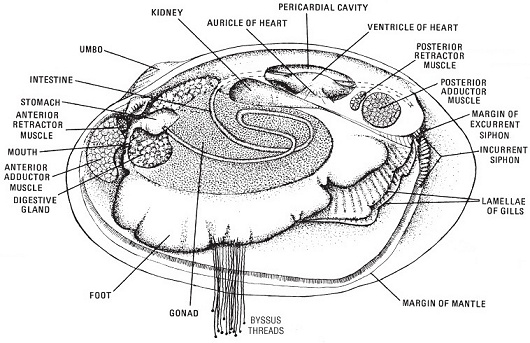

This worm-like creature is actually a bivalve mollusk with a greatly reduced shell, which it uses to bore tunnels into wood. They typically spend their entire lives in a tunnel in a single piece of wood. In addition to feeding off the wood, they can also filter feed like ordinary bivalves.

In the age of wooden ships, teredos and other wood-borers were a tremendous problem. In our area, more wood-boring is done by crustaceans than Teredos.

'Termites' of Sea Tell Rotten Tale

Shipworms, Gribbles Devour Bulkheads At Alarming Rate

By Ana M. Alay

Star-Ledger

January 27, 2004

For decades, the Hudson River and the waters of the metropolitan area ran thick with the contaminants of industry and the piers and wharves reeked of the foul fumes of factories. As pollution ebbed, the waterfront turned from toxic to gold, giving rise to luxury condominiums, marinas, hotels, and ferry terminals among the shipping ports. But lurking below the water is a new threat - the shipworm. Known as "termites of the sea, " the tiny, wood-eating creatures have become a growing nightmare for waterfront property owners, devouring millions of dollars worth of underwater timber.

As pollution has waned on the Hudson and New Jersey's coastal waters, shipworms and another type of marine borer known as the gribble are on an alarming comeback, officials say, transforming the wood in wharves, bulkheads, piers, and boats into a brittle honeycomb. "If you go back 25 years ago, marine borers weren't a problem, " said Casimir J. Bognacki, who heads a marine borer-monitoring program for the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. "There was too much pollution." Now, they're more widespread, Bognacki said. "They started showing up 15 years ago. In the past two years, they've been showing up in areas they didn't before."

The shipworms are forcing agencies and private owners to spend millions to repair or replace timber structures. Solutions can be pricey. In some cases, concrete is used to reinforce pilings, the long wood poles that are driven into a riverbed to support piers and wharves. In other cases, different types of plastic sheaths are wrapped around the underwater pilings to block the voracious marine mites.

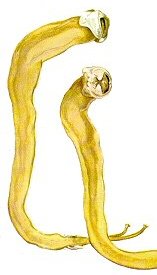

Shipworms, also called Teredos, are actually not worms. They are mollusks similar to clams, with worm-like bodies that live in saltwater or brackish water. They invade wood when they are at a larval stage and then start devouring the cellulose interior, growing up to a foot long, until the wood disintegrates. "Wherever you have untreated timber, you're going to have problems with shipworms, " said David M. Cacoilo, a partner and design engineer at Mueser Rutledge Consulting Engineers in New York, which has worked on a dozen marine borer projects. "Once they're there, the potential for the population to explode is tremendous."

Shipworms are not new. They've been a scourge for sailors and pier builders for centuries until pollution drove them away. During Columbus' fourth voyage to the Caribbean, he was forced to abandon two ships because of shipworm infestation. Another wood muncher giving marina owners grief is the gribble, also called Limnoria. This tiny saltwater isopod attacks the wood surface, reducing a piling to an hourglass shape.

Attack of the Marine Borers

Laurie Triefeldt,

Star Ledger

Shipworms Teredo navalis, also known as the sea worm or sea termite. Shipworms look like worms but are really bivalve mollusks related to clams. They invade wood when they are tiny larvae. Once inside the wood, this animal grows quickly and ranges in size from 6 inches to 6 feet in length. Shipworms create a honeycomb of holes in wood. The wood may look fine, except for a few small holes, but be entirely eaten away inside. It only takes two or three months for severe damage to occur. |  Gribbles Limnoria Iignprum, also known as a sea mite. Gribbles are tiny, almost microscopic crustaceans that resemble a woodlouse with seven pairs of legs and four pairs of mouthparts. They make up for their small size by attacking in huge numbers. They damage wood more slowly than the shipworm, but the damage is just as devastating. |

The gribbles and shipworms concern the Port Authority, which is currently overseeing three multimillion-dollar maintenance projects that include marine borer damage control. One project entails wrapping pilings with plastic at two Brooklyn piers. Another involves concrete reinforcement of pilings at a pier near the Holland Tunnel. At the Port Newark Marine Terminal, the authority is spending about $8 million on repairs, some specifically targeted to reduce borer damage to berths where ships load.

While the berths are not in danger of collapsing at the terminal, the Port Authority wants to protect them from further damage. "No one can predict the rate of loss, " said Robert C. Gill, an environmental analyst for the Port Authority. Variables that affect the rate of infestation include the type of wood, he said. Some piers and berths, often built with Douglas Fir or Southern Yellow Pine in the 1950s or '60s, are untreated. Others were treated with creosote, a distillate of coal tar that prevents borer attacks until the chemicals leach into the water.

In New York, the city's Department of Transportation spent $6.1 million for underwater surveys of borer damage to thousands of pilings supporting the Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harlem River Drives and two small bridges and is preparing to bid a multimillion-dollar contract for repairs. "The whole idea of this is to do it before it becomes unsafe and, quite frankly, to do it before it becomes expensive, " said Henry D. Perahia, deputy Transportation Commissioner for engineering in New York City.

NJ Transit has also been monitoring the marine borer problem since the mid-1990s and will replace infested pilings at the Hoboken Ferry Terminal with concrete-filled steel pipe pilings as part of a $79 million restoration project, according to Ken Hitchner, a spokesman for the agency. "The steel pipes will totally mitigate any kind of shipworm issue, " Hitchner said. "Steel isn't part of their diet."

Donald Launer, a lifelong sailor in Forked River, spent $18,000 to replace a shipworm-infested bulkhead with treated wood and vinyl parts. According to the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission, various studies agree that heated effluent from the Oyster Creek Nuclear Generating Station have increased the abundance of a tropical wood-boring species in the Barnegat Bay area. "It was obvious that the bulkhead was failing and when I went under to look, I found all these holes in it, " said Launer, an author who lectures on shipworms and other nautical issues. "The shipworms have attacked nearly every bulkhead in my lagoon."

In Edgewater, the shipworms have taken the spotlight in a multimillion-dollar civil suit. Owners of the 514-unit Independence Harbor Condominiums claim the developer is responsible for $18 million worth of repairs to the shipworm-damaged pier on which the homes were built. Dale Ludwig, president of the condo association, said when he bought his luxury home on the 1,500-foot pier in Edgewater, where a Ford Motor plant once shipped cars, trucks, and tanks in the 1920s, he was attracted to the Manhattan skyline and scenic river view. He didn't know about shipworms. "I had no clue, " said Ludwig. "We're homeowners, not experts in everything." Lawyers for the developer, Hartz Mountain Industries, claim the marine borer infestation is not at a level that threatens the structural integrity of the pier. They claim the salinity of the water is lower there than in the lower Hudson River, where most of the serious borer damage is occurring.

Andy Willner, the NY-NJ Baykeeper, said despite the cost of the shipworm problem, environmentalists are cheering the return of the marine borers because they indicate the river is cleaning up. "I guess it's called hubris when people build something they think can't be attacked by wind or water, " Willner said. "Nature wins in the end. I guess you could say this is a very late lunch bill coming in."