Manasquan Wreck - Amity

- Type:

- shipwreck, sailing ship, USA

- Built:

- 1816, New York NY, USA

- Specs:

- 382 tons

- Sunk:

- Saturday April 24, 1824

ran aground in a fog - no casualties - Depth:

- 30 ft

The Amity was the second of the original four Black Ball packet ships. The Black Ball Line was the first company to offer scheduled trans-Atlantic service. Prior to that, ships made the crossing whenever they had a profitable cargo, on no set timetable. The Amity ended her career on schedule, but in the wrong place - hard aground on the beach at Manasquan.

The passengers and crew were rescued, and much of the Amity's cargo was salvaged, except for that in the lower holds, which was abandoned since by then the ship was breaking up. The earliest divers brought up a great deal of old tools and hardware, packed in wooden barrels. What remains today is a low wooden debris field, 330 yards offshore, now buried.

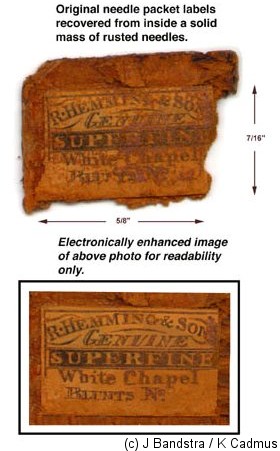

Sewing Needle Packet Labels

These artifacts were important to the actual identification of the site by John Bandstra and Ken Cadmus in 1995. They were recovered from a dried rusted mass of sewing needles that were originally packed in small envelopes as they are to this day. While the envelopes were completely disintegrated after 171 years of being in the ocean, the labels on those envelopes survived, due to the fact that they were printed on "black paper", which is similar to the paper used for currency. After extracting them, they were reconstructed digitally to make the wording more readable. The needles were produced in Redditch, England by the firm, R. Hemming & Son during the 1820s.

Brass Button

This brass gilt button eluded identification for 40 years since the wreck's discovery in 1955, again because of its lack of a name of manufacture. However, the British Button Society was able to identify its style as being made by Smith & Wright of Birmingham, England in the 1820s. The wording on the button, "Extra Rich" meant that it was dipped in gold plating twice ( to make it glisten and be corrosion-free), but the word "London" was simply used for advertising. Nothing of this sort was ever produced in London. Early divers recovered these buttons by the thousands and they were originally thought to be British Revolutionary War uniform buttons. They later proved to be merely gold-plated men's suit buttons of the 1820s. Shipping lists name them as "uniform buttons", which confused previous attempts to identify them.

Artifact images and descriptions courtesy of John Bandstra and Ken Cadmus

Questions or Inquiries?

Just want to say Hello? Sign the .