Andrea Doria (6/7)

Everest At the Bottom Of the Sea

reprinted from Esquire magazine, July 2000

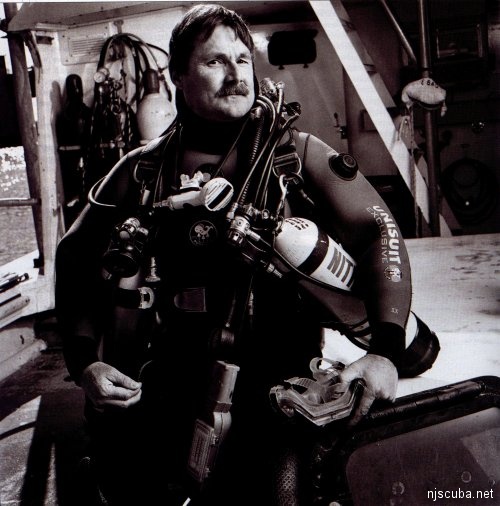

WHEN THE OCEAN LINER ANDREA DORIA SANK SOUTH OF CAPE COD, SHE TOOK FIFTY-ONE WITH HER. SINCE THEN, SHE'S TAKEN TWELVE MORE, FIVE IN THE LAST TWO SUMMERS ALONE. ON THIS VERY DAY, A MAN IS STRAPPING ON TWO HUNDRED POUNDS OF SCUBA GEAR TO MAKE THE DESCENT, TO BRING BACK A LITTLE SOUVENIR FROM THE BOAT'S GIFT SHOP, TO POSSIBLY NEVER RETURN.

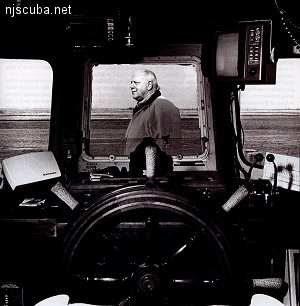

The man in the iron mask is Dan Crowell, captain of the SEEKER, the reigning master of the Doria deep.

ARRIVAL

You toss in your seaman's bunk and dream the oldest, oddest beachcomber's dream: Something has siphoned away all the waters of the seas, and you're taking a cold, damp hike down into the world's empty pool. Beer cans, busted pipes, concrete blocks, grocery carts, a Cadillac on its back, all four tires missing - every object casts a long, stark shadow on the puddled sand. With the Manhattan skyline and the Statue of Liberty behind you, you trek due cast into the sunrise, following the toxic trough of the Hudson River's outflow known to divers in these parts as the Mudhole until you arrive, some miles out, at Wreck Valley.

You see whole fishing fleets asleep on their sides and about a million lobsters crawling around like giant cockroaches, waving confounded antennae in the thin air. Yeah, what a dump of history you see, a real Coney Island of catastrophes. The greatest human migration in the history of the world passed through here, first in a trickle of dauntless hard-asses, and then in that famous flood of huddled masses, Western man's main manifest destiny arcing across the northern ocean. The whole story is written in the ruins: in worm-ridden middens, mere stinking piles of mud; in tall ships chewed to fish-bone skeletons; five-hundred-foot steel-plated cruisers plunked down onto their guns; the battered cigar tubes of German U-boats; and sleek yachts scuttled alongside sunken tubs as humble as old boots.

You can't stop to poke around or fill your pockets with souvenirs. You're on a journey to the continent's edge, where perhaps the missing water still pours into the Atlantic abyss with the tremendous roar of a thousand Niagaras. Something waits there that might explain, and that must justify, your presence in this absence, this scooped-out plain where no living soul belongs. And you know, with a sudden chill, that only your belief in the dream, the focus of your mind and your will on the possibility of the impossible, holds back the annihilating weight of the water.

YOU WAKE UP IN the DARK and for a moment don't know where you are, until you hear the thrum of the diesel and feel the beam roll. Then you realize that what awakened you was the abrupt decrease of noise, the engine throttling down, and the boat and the bunk you lie in subsiding into the swell, and you remember that you are on the open sea, drawing near to the wreck of the Andrea Doria. You feel the boat lean into a turn, cruise a little ways, and then turn again, and you surmise that up in the pilothouse, Captain Dan Crowell has begun to "mow the lawn, " steering the sixty-foot exploration vessel the SEEKER back and forth, taking her through a series of slow passes, sniffing for the Doria.

The Doria entering New York Harbor after her first crossing, January 1953.

Crowell, whom you met last night when you hauled your gear aboard, is a big, rugged-looking guy, about six feet two inches in boat shoes, with sandy brown hair and a brush mustache. Only his large, slightly hooded eyes put a different spin on his otherwise gruff appearance; when he blinks into the green light of the sonar screen, he resembles a thoughtful sentinel owl. Another light glows in the wheelhouse: a personal computer, integral to the kind of technical diving Crowell loves.

The SEEKER's crew of five divvies up hour-and-a-half watches for the ten-hour trip from Montauk, Long Island, but Crowell will have been up all night in a state of tense vigilance. A veteran of fifty Doria trips, Crowell considers the hundred-mile cruise - both coming and going - to be the most dangerous part of the charter, beset by imminent peril of fog and storm and heavy shipping traffic. It's not for nothing that mariners call this patch of ocean where the Andrea Doria collided with another ocean liner the "Times Square of the Atlantic."

You feel the SEEKER's engine back down with a growl and can guess what Crowell is seeing now on the forward-looking sonar screen: a spattering of pixels, like the magnetic shavings on one of those draw-the-beard slates, coalescing into partial snapshots of the seven-hundred foot liner. What the sonar renders is but a pallid gray portrait of the outsized bulk, which, if it stood up on its stern on the bottom, 250 feet below, would tower nearly fifty stories above the SEEKER, dripping and roaring like Godzilla. Most likely you're directly above her now, a proximity you feel in the pit of your stomach. As much as the physical wreck itself, it's the Doria legend you feel leaking upward through the SEEKER's hull like some kind of radiation.

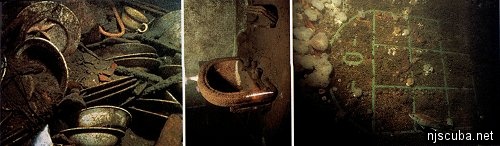

"The Mount Everest of scuba diving, " people call the wreck, in another useful catchphrase. Its badass rep is unique in the sport. Tell a fellow diver you've done the Great Barrier Reef or the Red Sea, they think you've got money. Tell 'em you've done the Doria, they know you've got balls. Remote enough to expose you to maritime horrors - the SEEKER took a twenty-five-foot wave over its bow on a return trip last summer - the Doria's proximity to the New York and New Jersey coasts has been a constant provocation for two generations. The epitome, in its day, of transatlantic style and a luxurious symbol of Italy's post-World War II recovery, the Andrea Doria has remained mostly intact and is still full of treasure: jewelry, art, an experimental automobile, bottles of wine - plus mementos of a bygone age, like brass Shuffleboard numbers and silver and china place settings, not so much priceless in themselves but much coveted for the challenge of retrieving them.

But tempting as it is to the average wreck diver, nobody approaches the Doria casually. The minimum depth of a Doria dive is 180 feet, to the port-side hull, well below the 130 foot limit of recreational diving. Several years of dedicated deep diving is considered a sane apprenticeship for those who make the attempt - that, plus a single-minded focus that subsumes social lives and drains bank accounts. Ten thousand dollars is about the minimum ante for the gear and the training and the dives you need to get under your belt. And that just gets you to the hull and hopefully back. For those who wish to penetrate the crumbling, maze-like interior, the most important quality is confidence bordering on hubris: trust in a lucid assessment of your own limitations and belief in your decision-making abilities, despite the knowledge that divers of equal if not superior skill have possessed those same beliefs and still perished.

CROWELL'S RIVAL, Steve Bielenda, aboard the Wahoo. "If it takes five deaths to be the number one Doria boat, " he says, "I'm happy being number two."

PROPPED UP ON YOUR ELBOWS, you look out the salon windows and see the running lights of another boat maneuvering above the Doria. It's the Wahoo, owned by Steve Bielenda and a legend in its own right for its 1992 salvage of the seven hundred pound ceramic Gambone panels, one of the Doria's lost art masterpieces. Between Bielenda, a sixty-four-year-old native of Brooklyn, and Crowell, a transplanted Southern Californian who's twenty years younger and has gradually assumed the lion's share of the Doria charter business, you have the old King of the Deep and the heir apparent. And there's no love lost between the generations.

"If these guys spent as much time getting proficient as they do avoiding things, they'd actually be pretty good" is Crowell's backhanded compliment to the whole "Yo, Vinny!" attitude of the New York - New Jersey old school of gorilla divers. Bielenda, for his part, has been more pointed in his comments on the tragedies of the 1998 and 1999 summer charter seasons, in which five divers died on the Doria, all from aboard the SEEKER. "If it takes five deaths to make you the number-one Doria boat, " Bielenda says, "Then I'm happy being number two." He also takes exception to the SEEKER's volume of business - ten charters in one eight-week season. "There aren't enough truly qualified divers in the world to fill that many trips, " Bielenda says.

To which Crowell's best response might be his piratical growl, "Arrgh!" which sums up his exasperation with the fractious politics of diving in the Northeast. He says he's rejected divers who've turned right around and booked a charter on the Wahoo. But, hell, that's none of his business. His business is making the SEEKER's criteria for screening divers the most coherent in the business, which Crowell believes he has. Everyone diving the Doria from the SEEKER has to be Trimix certified, a kind of doctoral degree of dive training that implies you know a good deal about physiology, decompression, and the effects of helium and oxygen and nitrogen on those first two. That, or be enrolled in a Trimix course and be accompanied by an instructor, since, logically, where else are you gonna learn to dive a deep wreck except on a deep wreck?

As for the fatalities of the last two summer seasons - "five deaths in thirteen months" is the phrase that has been hammered into his mind - Crowell has been forthcoming with reporters looking for a smoking gun onboard the SEEKER and with fellow divers concerned about mistakes they might avoid. "If you took at the fatalities individually, you'll see that they were coincidental more than anything else, " Crowell has concluded. In a good season, during the fair-weather months from June to late August, the SEEKER will put about two hundred divers on the Doria.

Nobody is more familiar with the cruel Darwinian exercise of hauling a body home from the Doria than Crowell himself, who has wept and cursed and finally moved on to the kind of gallows humor you need to cope. He'll tell you about his dismay at finding himself on a first-name basis with the paramedics that met the SEEKER in Montauk after each of the five fatalities - how they tried to heft one body still in full gear until Crowell reached down and unhooked the chest harness, tightening the load by a couple of hundred pounds. Another they tried to fit into a body bag with the fins still on his feet.

But beyond their sobering effect on those who've made the awful ten-hour trip home with the dead, the accidents have not been spectacularly instructive. Christopher Murley, forty-four, from Cincinnati, had an outright medical accident, a heart attack on the surface. Vince Napoliello, a thirty-one-year-old bond salesman from Baltimore and a friend of Crowell's, "just a good, solid diver, " was a physiological tragedy waiting to happen; his autopsy revealed a 90 percent obstructed coronary artery. Charlie McGurr? Another heart attack. And Richard Roost? A mature, skilled diver plain shit-out-of-luck, whose only mistake seems to have been a failure to remain conscious at depth, which is never guaranteed. Only the death of Craig Sicola, a New Jersey housebuilder, might fit the criticism leveled at the SEEKER in Internet chat rooms and God knows where else - that a super-competitive atmosphere, and a sort of taunting elitism projected by the SEEKER's captain and his regular crew, fueled the fatalities of the last two seasons.

Did Sicola, soloing on his second trip, overreach his abilities? Maybe so, but exploring the wreck, and yourself in the process, is the point of the trip. "You might be paying your money and buying your ticket just like at Disney World, but everybody also knows this is a real expedition, " says Crowell. "You've got roaring currents, low visibility, often horrible weather, and you're ten hours from help. We're pushing the limits out here."

ALL THIS YOU KNOW BECAUSE, like most of the guys on the charter, you're sort of a Doria buff ... well, maybe a bit of a nut. You wouldn't be out here if you weren't. A lot of the back story you know by heart. How on the night of July 25, 1956, the Andrea Doria ( after the sixteenth-century Genoese admiral ), 29,083 tons of la dolce vita, festively inbound for New York Harbor, steamed out of an opaque fogbank at a near top speed of twenty-three knots and beheld the smaller, outbound Swedish liner Stockholm making straight for her. The ships had tracked each other on radar but lined up head-on at the last minute. The Stockholm's bow, reinforced for ice-breaking in the North Sea, plunged thirty feet into the Doria's starboard side, ripping open a six-story gash. One Doria passenger, Linda Morgan, who became known as the miracle girl, flew from her bed in her nightgown and landed on the forward deck of the Stockholm, where she survived. Her sister, asleep in the bunk below, was crushed instantly. In all, fifty-one people died.

Eleven hours after the collision, the Andrea Doria went down under a froth of debris, settling onto the bottom on her wounded starboard side in 250 feet of cold, absinthe-green seawater. The very next day, Peter Gimbel, the department store heir ( he hated like hell to be called that ) and underwater filmmaker, and his partner, Joseph Fox, made the first scuba dive to the wreck, using primitive double-hosed regulators. The wreck they visited was then considerably shallower ( the boat has since collapsed somewhat internally and hunkered down into the pit the current is gouging ) and uncannily pristine; curtains billowed through portholes, packed suitcases knocked around in tipped-over staterooms, and shoes floated in ether. That haunted-house view obsessed Gimbel, who returned, most famously, for a month-long siege in 1981. Employing a diving bell and saturation-diving techniques, Gimbel and crew blowtorched through the first-class loading-area doors, creating "Gimbel's Hole, " a garage-door sized aperture amidships, still the preferred entry into the wreck, and eventually raised the Bank of Rome safe. When Gimbel finished editing his film, the Mystery of the Andrea Doria, in an event worthy of Geraldo, the safe was opened on live TV. Stacks of waterlogged cash were revealed, though much less than the hoped-for millions.

In retrospect, the "mystery" and the safe seem to have been invented after the fact to justify the diving. Gimbel was seeking something else. He had lost his twin brother to illness some years before, an experience that completely changed his life and made of him an explorer. He got lost in jungles, filmed great white sharks from the water. And it was while tethered by an umbilicus to a decosphere the divers called Mother, hacking through shattered walls and hauling out slimed stanchions in wretchedly constrained space and inches of visibility, always cold, that Gimbel believed he encountered and narrowly escaped a "malevolent spirit, " a spirit he came to believe inhabited the Doria.

But while Gimbel sought absolute mysteries in a strongbox, salvagers picked up other prizes - the Andrea Doria's complement of fine art, such as the Renaissance-style life-sized bronze statue of Admiral Doria, which divers hacksawed off at the ankles. The wreckage of the first-class gift shop has yielded trinkets of a craftsmanship that no longer exists today - like Steve Bielenda's favorite Doria artifact, a silver tea fob in the form of a locomotive with its leather thong still intact. A handful of Northeastern deep divers who knew one another on a first-name basis ( when they were on speaking terms, that is ) spread the word that it was actually fun to go down in the dark. And by degrees, diving the Doria and its two-hundred-foot-plus interior depths segued from a business risk to a risky adventure sport. In the late eighties and early nineties, there was a technical-diving boom, marked by a proliferation of training agencies and a steady refinement of gear. Tanks got bigger, and mixed gases replaced regular compressed air as a "safer" means of diving at extreme depths.

Every winter, the North Atlantic storms give the wreck a tough shake, and new prizes tumble out, just waiting for the summer charters. The SEEKER has been booked for up to three years in advance, its popularity founded on its reputation for bringing back artifacts. The most sought-after treasure is the seemingly inexhaustible china from the elaborate table settings for 1,706 passengers and crew. First-class china, with its distinctive maroon-and-gold bands, has the most juju, in the thoroughly codified scheme of things. It's a strange fetish, certainly, for guys who wouldn't ordinarily give a shit about the quality of a teacup and saucer. Bielenda and Crowell and their cronies have so much of the stuff that their homes look as if they were decorated by maiden aunts.

Yet you wouldn't mind a plate of your own and all that it would stand for. You can see it in your mind's eye - your plate and the getting of it - just as you saw it last night on the cruise out, when someone popped one of Crowell's underwater videos into the VCR. The thirty-minute film, professionally done from opening theme to credits, ended beautifully with the SEEKER divers fresh from their triumphs, still blushing in their drysuits like lobsters parboiled in adrenaline, holding up Doria china while Vivaldi plays. A vicarious victory whose emotions were overshadowed, You're sorry to say, by the scenes inside the Doria, and specifically by the shots of Doria china, gleaming bone-white in the black mud on the bottom of some busted metal closer who knew how far in or down how many blind passageways. Crowell had tracked it down with his camera and put a beam on it: fine Genoa china, stamped ITALIA, with a little blue crown. The merit badge of big-boy diving, the artifact that says it best: I fuckin' did it - I dove da Doria! Your hand reaches out ...

THE CABIN DOOR OPENS and someone comes into the salon, just in time to cool your china fever. It's Crowell's partner Jenn Samulski, who keeps the divers' records and cooks three squares a day. Samulski, an attractive blond from Staten Island who has been down to the Doria herself, starts the coffee brewing, and eyes pop open, legs swing out over the sides of the bunks, and the boat wakes up to sunrise on the open sea, light glinting off the steely surface and the metal rows of about sixty scuba tanks weighing down the stern.

On a twelve-diver charter, personalities range from obnoxiously extroverted to fanatically secretive - every type of type A, each man a monster of his own methodology. But talk is easy when you have something humongous in common, and stories are the coin of the lifestyle. You know so-and-so? someone says around a mouthful of muffin. Wasn't he on that dive back in '95? And at once, you're swept away by a narrative, this one taking you to the wreck of the Lusitania, where an American, or a Brit maybe - somebody's acquaintance, somebody's friend - is diving with an Irish team. He gets entangled, this diver does, in his own exploration line, on the hull down at 280 feet. His line is just pooling all around him and he's thrashing, panicking, thinking - as everybody always does in a panic - that he has to get to the surface, like right away. So he inflates his buoyancy compensator to the max, and now he's like a balloon tied to all that tangled line, which the lift of the BC is pulling taut. He's got his knife out, and he's hacking away at the line. One of the Irish divers sees what's happening and swims over and grabs the guy around the legs just as the last line is cut. They both go rocketing for the surface, this diver and his pumped-up BC and the Irishman holding on to him by the knees. At 160 feet, the Irishman figures, Sorry, mate, I ain't dying with you, and has to let him go. So the diver flies up to the top and bursts internally from the violent change of depth and the pressurized gas, which makes a ruin of him.

Yeah, he should never have been diving with a line, someone points out, and a Florida cave diver and a guy from Jersey rehash the old debate - using a line for exploration, the cave diver's practice, versus progressive penetration, visual memorization of the wreck and the ways out. Meanwhile, a couple of the SEEKER's crew members have already been down to the wreck to set the hook. The rubber chase boat goes over the bow, emergency oxygen hoses are lowered off the port-side rail, and Crowell tosses out a leftover pancake to check the current. It slaps the dead-calm surface, spreading ripples, portals widening as it drifts aft. Because the Doria lies close to the downfall zone, where dense cold water pours over the continental shelf and down into the Atlantic Trench, the tidal currents can be horrendously strong. Sometimes a boat anchored to the Doria will carve a wake as if it were underway, making five knots and getting nowhere. An Olympic swimmer in a Speedo couldn't keep up with that treadmill, much less a diver in heavy gear. And sometimes the current is so strong, it'll snap a three-quarter-inch anchor line like rotten twine. But on this sunny July morning, already bright and hearing tip fast, Crowell blinks beneath the bill of his cap at the bobbing pancake and calculates the current at just a couple of knots - not too bad at all, if you're ready for it. Crowell grins at the divers now crowded around him at the stern. "Pool's open, " he says.

The DIVE

YOU CAN NEVER GET USED TO the weight. When you wrestle your arms into the harness of a set of doubles, two 120 cubic foot capacity steel tanks yoked together on metal plates, you feel like an ant, one of those leaf-cutter types compelled to heft a preposterous load. What you've put on is essentially a wearable submarine with its crushed neoprene drysuit shell and its steel external lungs and glass-enclosed command center. Including a pony-sized emergency bottle bungee-strapped between the steel doubles and two decompression tanks clipped to your waist, you carry five tanks of gas and five regulators. You can barely touch your mittened hands together in front of you around all the survival gear, the lift bags, lights, reels, hoses, and instrument consoles. And yet, for all its awkwardness on deck, a deep-diving rig is an amazing piece of technology, and if you don't love it at least a little you had better never put it on. It's one thing you suppose you all have in common on this charter-stockbrokers, construction workers, high school teachers, cops - you're all Buck Rogers flying a personal ship through inner space.

The immediate downside is that you're slightly nauseated from reading your gauges in a four-foot swell, and inside your drysuit, in expedition-weight socks and polypropylene long johns, you're sweating bullets. The way the mind works, you're thinking, "To hell with this bobbing world of sunshine and gravity" - you can't wait to get wet and weightless. You strain up from the gearing platform hefting nearly two hundred pounds and duckwalk a couple of steps to the rail, your fins smacking the deck and treading on the fins of your buddies who are still gearing up.

Some of the experienced Doria divers from Crowell's crew grasp sawed-off garden rakes with duct-taped handles, tools they'll use to reach through rubble and haul in china from a known cache. Crowell gestures among them, offering directions through the Doria's interior maze. Your goal is just to touch the hull, peer into Gimbel's Hole. An orientation dive. You balance on the rail like old Humpty-Dumpty and crane your neck to see if all's clear on the indigo surface. Scuba lesson number one: Most accidents occur on the surface. There was a diver last summer, a seasoned tech diver, painstaking by reputation, on his way to a wreck off the North Carolina coast. Checked out his gear en route - gas on, take a breath, good, gas off - strapped it on at the site, went over the side, and sank like a dirt dart. His buddies spent all morning looking for him everywhere except right under their boat, where he lay, drowned. He had never turned back on his breathing gas.

And there was a diver on the SEEKER who went over the side and then lay sprawled on his back in the water, screaming, "Help! Help!" What the fuck was the matter with the guy? Turns out he'd never been in a drysuit before and couldn't turn himself over. Crowell wheeled on the guy's instructor. "You brought him out here to make his first drysuit dive on the Doria? Are ya crazy?" then the instructor took an underwater scooter down with him, and he had to be rescued with the chase boat. Arrgh! Crowell laments that there are divers going from Open Water, the basic scuba course, to Trimix in just fifty dives; they're book-smart and experience-starved. And there are bad instructors and mad instructors, egomaniacal, guru-like instructors.

"You will dive only with me, " Crowell says, parodying the Svengalis. "Or else it's a thousand bucks for the cape with the clouds and the stars on it. Five hundred more and I'll throw in the wand." "Just because you're certified don't make you qualified" is Steve Bielenda's motto, and it's the one thing the two captains can agree on.

You take a couple of breaths from each of your regs. Click your lights on and off. You press the inflator button and puff a little more gas into your buoyancy compensator, the flotation wings that surround your double 120s, and experience a tightening and a swelling up such as the Incredible Hulk must feel just before his buttons burst. Ready as you'll ever be, you plug your primary reg into your mouth and tip the world over ... and hit the water with a concussive smack. At once, as you pop back up to the surface before the bubbles cease seething between you and the image of the SEEKER's white wooden hull, rocking half in and half out of the water, you're in conflict with the current. You grab the floating granny line and it goes taut and the current dumps buckets of water between your arms and starts to rooster-tail around your tanks. This is two knots? You're breathing hard by the time you haul yourself hand over hand to the anchor line, and that's not good. Breath control is as important to deep divers as it is to yogis. At two hundred feet, just getting really excited could knock you out like a blow from a ball-peen hammer. As in kill you dead. So you float a moment at the surface, sighting down the parabola of the anchor line to the point where it vanishes into a brownish-blue gloom. Then you reach up to your inflator hose and press the other button, the one that splutters outgas from the BC, and feel the big steel 120s reassert their mass, and calmly, feet first, letting the anchor line slide through your mitts, you start to sink.

FOR the THIN AIR OF EVEREST, which causes exhaustion universally and pulmonary and cerebral events ( mountain sickness ) seemingly randomly, consider the "thick" air you must breathe at 180 feet, the minimum depth of a dive to the Doria. Since water weighs sixty-four pounds per cubic foot ( and is eight hundred times as dense as air ), every foot of depth adds significantly to the weight of the water column above you. You feel this weight as pressure in your ears and sinuses almost as soon as you submerge. Water pressure doesn't affect the gas locked in your noncompressible tanks, of course, until you breathe it. Then, breath by breath, thanks to the genius of the scuba regulator - Jacques Cousteau's great invention - the gas becomes ambient to the weight of the water pressing on your lungs. That's why breathing out of steel 120s pumped to a pressure of 7,000 psi isn't like drinking out of a fire hose, and also why you can kick around a shallow reef at twenty feet for an hour and a half, while at a hundred feet you'd suck the same tank dry in twenty minutes; you're inhaling many times more molecules per breath.

Unfortunately, it's not all the same to your body how many molecules of this gas or the other you suck into it. On the summit of Everest, too few molecules of oxygen makes you light-headed, stupid, and eventually dead. On the decks of the Doria, too many molecules of oxygen can cause a kind of electrical fire in your central nervous system. You lose consciousness, thrash about galvanically, and inevitably spit out your regulator and drown. A depth of 216 feet is generally accepted as the point at which the oxygen in compressed air ( which is 21 percent oxygen, 79 percent nitrogen ) becomes toxic and will sooner or later ( according to factors as infinitely variable as individual bodies ) kill you. As for nitrogen, it has two dirty tricks it can play at high doses. It gets you high - just like the nitrous oxide that idiot adolescents huff and the dentist dispenses to distract you from a root canal - starting at about 130 feet for most people. "I am personally quite receptive to nitrogen rapture, " Cousteau writes in the Silent World. "I like it and fear it like doom."

The fearsome thing is that, like any drunk, you're subject to mood swings, from happy to sad to hysterical and panicky when you confront the dumb thing you've just done, like getting lost inside a sunken ocean liner. The other bad thing nitrogen does is deny you permission to return immediately to the surface, every panicking person's solution to the trouble he's in. It's the excess molecules of nitrogen lurking in your body in the form of tiny bubbles that force you to creep back up to the surface at precise intervals determined by time and depth. On a typical Doria dive, you'll spend twenty-five minutes at around two hundred feet and decompress for sixty-five minutes at several stopping points, beginning at 110 feet. While you are hanging on to the anchor line, you're off-gassing nitrogen at a rate the body can tolerate. Violate deco and you are subject to symptoms ranging from a slight rash to severe pain to quadriplegia and death. The body copes poorly with big bubbles of nitrogen trying to fizz out through your capillaries and bulling through your spinal column, traumatizing nerves.

Enter Trimix, which simply replaces some of the oxygen and nitrogen in the air with helium, giving you a life-sustaining gas with fewer molecules of those troublesome components of air. With Trimix, you can go deeper and stay longer and feel less narced. Still, even breathing Trimix at depth can be a high-wire act, owing to a third and final bad agent: carbon dioxide. The natural by-product of respiration also triggers the body's automatic desire to replenish oxygen. When you hyperventilate - take rapid, shallow breaths - you deprive yourself of CO2 and fool the body into believing it doesn't need new oxygen. Breath-hold divers will hyperventilate before going down as a way to gain an extra minute or two of painless 02 deprivation. But at depth ( for reasons poorly understood ), hypercapnia, the retention of C02 molecules, has the same "fool the brain" effect. It's a tasteless, odorless, warningless fast track to unconsciousness. One moment you are huffing and puffing against the current, and the next you are swimming in the stream of eternity.

Richard Roost, a forty-six-year-old scuba instructor from Ann Arbor, Michigan, one of the five Doria fatalities of the last two seasons, was highly skilled and physically fit. His body was recovered from the Doria's first-class lounge, a large room full of shattered furniture deep in the wreck. It's a scary place, by all accounts, but Roost seemed to be floating in a state of perfect repose. Though he had sucked all the gas from his tanks, there was no sign that he had panicked. Crowell suspects that he simply "took a nap, " a likely victim of hypercapnia.

SO IT IS THAT YOU STRIVE TO SINK with utter calm, dumping a bit of gas into your drysuit as you feel it begin to vacuum-seal itself to you, bumping a little gas into the BC to slow your rate of descent, seeking neutrality, not just in buoyancy but in spirit as well. Soon you've sunk to that zone where you can see neither surface nor bottom. It's an entrancing, mystical place - pure inner space. Things appear out of nowhere - huge, quick things that aren't there, blocks of blankness, hallucinations of blindness. Drifting, drifting ... reminds you of something Steve Bielenda told you: "The hard part is making your brain believe this is happening. But, hey, you know what? It really is happening!" You focus on the current-borne minutiae - sea snow, whale food, egg-drop soup - which whizzes by outside the glass of your mask like a sepia-colored silent movie of some poor sod sinking through a blizzard.

Your depth gauge reads 160 feet, and you hit the thermocline, the ocean's deep icebox layer. The water temp plunges to 45 degrees and immediately numbs your cheeks and lips. Your drysuit is compressed paper-thin; you don't know how long you can take the cold, and then something makes you forgetful about it completely: the Doria, the great dome of her hull falling away into obscurity, and the desolate rails vanishing in both directions, and a lifeboat davit waving a shred of trawler net like a hankie, and the toppled towers of her superstructure. And it's all true what they've said: You feel humbled and awed. You feel how thin your own audacity is before the gargantuan works of man. You land fins-first onto the steel plates, kicking up two little clouds of silt. Man on the moon.

You've studied the deck plans of the Grande Dame of the Sea - her intricacy and complexity and order rendered in fine architectural lines. But the Doria looks nothing like that now. Her great smokestack has tumbled down into the dark debris field on the seafloor. Her raked-back aluminum forecastle decks have melted like a Dali clock in the corrosive seawater. Her steel hull has begun to buckle under its own weight and the immense weight of water, pinching in and splintering the teak decking of the promenade, where you kick along, weaving in and out of shattered windows. Everything is moving: bands of water, now cloudy, now clear, through which a blue shark twists in and out of view; sea bass darting out to snatch at globs of matter stirred up by your fins. They swallow and spit and glower. Everywhere you shine your light inside, you see black dead ends and washed-out walls and waving white anemones like giant dandelions blowing in a breeze.

You rise up a few feet to take stock of your location and see that on her outer edges she is Queen of Snags, a harlot tarred up with torn nets, bristling with fishermen's monofilament and the anchor lines of dive boats that have had to cut and run from sudden storms. She's been grappled more times than Moby Dick, two generations of obsessed Ahabs finding in her sheer outrageous bulk the sinews of an inscrutable malice, a dragon to tilt against. In your solitude you sense the bleak bitch of something unspeakably larger still, something that shrinks the Doria down to the size of Steve Bielenda's toy-train tea fob: a hurricane of time blowing through the universe, devouring all things whole.

ON the AFT DECK OF the WAHOO, Steve Bielenda, a fireplug of a man, still sinewy in his early sixties, is kicked back in his metal folding-chair throne. He wears his white hair in a mullet cut and sports a gold earring. He was wild as a kid, by his own account, a wiseguy, wouldn't listen to nobody. The product of vocational schools, he learned auto mechanics and made a success of his own repair shop before he caught the scuba bug. Then he would go out with fishermen for a chance to dive - there weren't any dive boats then - and offered his services as a salvage diver, no job too small or too big. When he sold his shop and bought the Wahoo, it was the best and the biggest boat in the business. Now, as the morning heats up, he's watching the bubbles rise and growling out Doria stories in his Brooklyn accent. "When you say Mount Everest to somebody, " he says, "you're sayin' something. Same with da Doria. It was the pinnacle wreck. It was something just to go there."

TEACUPS and saucers and delicate trinkets might seem a strange fetish for tough guys, but they are bounty that say one thing: I did it! I dove the Doria!

And go there he did - more than a hundred times. The first time in '81, with a serious Doria fanatic, Bill Campbell, who had commissioned a bronze plaque to commemorate the twenty-fifth anniversary of the sinking; and often with maritime scholar and salvager John Moyer, who won salvage rights to the Doria in federal court and hired the Wahoo in '92 to put a "tag" on the wreck - a tube of PVC pipe, sealed watertight, holding the legal papers. Tanks were much smaller then, dinky steel 72s and aluminum 80s, compared with the now-state-of-the-art 120-cubic-foot-capacity tanks. "You got air, you got time, " is how Bielenda puts it. And time was what they didn't have down at 180 feet on the hull. It was loot and scoot. Guys were just guessing at their decompression times, since the U. S. Navy Dive Tables expected that nobody would be stupid or desperate enough to make repetitive dives below 190 feet with scuba gear. "Extrapolating the tables" was what they called it; it was more like pick a lucky number and hope for the best. But Bielenda's quick to point out that in the first twenty-five years of diving the Doria, nobody died. Back then the players were all local amphibians, born and bred to cold-water diving and watermen to the nth degree. Swimming, water polo, skin diving, then scuba, then deep scuba - you learned to crawl before you walked in those days.

A thousand things you had to learn first. "You drive through a tollbooth at five miles an hour - no problem, right? Try it at fifty miles an hour. That hole gets real small! That's divin' da Doria. To dive da Doria it's gotta be like writin' a song, " the captain says, and he hops up from his chair and breaks into an odd little dance, shimmying his 212 pounds in a surprisingly nimble groove, tapping himself here, here, here - places a diver in trouble might find succor in his gear. "And you oughta wear yet mask strap under yer hood, " he tells a diver who's gearing up. "There was this gal one time ..." and Bielenda launches into the story about how he saved Sally Wahrmann's life with that lesson.

She was down in Gimbel's Hole, just inside it and heading for the gift shop, when this great big guy - John Ornsby was his name, one of the early Doria fatalities - comes flying down into the hole after her and just clobbers her. "He rips her mask off and goes roaring away in a panic, " Bielenda says. "But see, she has her mask under her hood like I taught her, so she doesn't lose it. It's still right there around her neck."

The blow knocked Wahrmann nearly to the bottom of the wreck, where an obstruction finally stopped her fall seven sideways stories down. But she never panicked, and with her mask back on and cleared, she could find her way out toward the tiny speck of green light that was Gimbel's Hole, the way back to the world. "She climbs up onto the boat and gives me a big kiss. 'Steve, ' she says, 'you just saved my life.' "

As for Ornsby, a Florida breath-hold diver of some renown, his banzai descent into Gimbel's Hole was never explained, but he was found dead not fit from the entrance, all tangled up in cables as if a giant spider had been at him. It took four divers with cable cutters two dives each to cut the body free. Bielenda has been lost inside of wrecks and has found his way out by a hairbreadth. He and the Wahoo have been chased by hurricanes. One time he had divers down on the Doria when a blow came up. He was letting out anchor line as fast as he could, and the divers, who were into decompression, they were scrambling up the line hand over hand to hold their depth. The swells rose up to fifteen feet, and Bielenda could see the divers in the swells hanging on to the anchor line, ten feet underwater but looking down into the Wahoo! A Doria sleigh ride - that's the kind of memories the Doria's given him. Strange sights indeed. He knows he's getting too old for the rigors of depth, but he's not ready to let go of the Doria yet, not while they still have their hooks in each other.

UP IN the PILOTHOUSE of the SEEKER, Dan Crowell is fitting his video camera into its watertight case, getting ready to go down and shoot some footage inside the wreck. He tries to make at least one dive every charter trip, and he never dives without his camera anymore if he can help it.

The more you learn about Crowell, the more impressed you are. He's a voracious autodidact who sucks up expertise like a sponge. He has worked as a commercial artist, a professional builder, a commercial diver, and a technical scuba instructor, as well as a charter captain. His passion now is shooting underwater video, making images of shipwrecks at extreme depths. His footage of the Britannic was shot at a whopping depth of 400 feet. When Crowell made his first Doria dive in 1990, a depth of 200 feet was still Mach 1, a real psychological and physical barrier. He remembers kneeling in the silt inside Gimbel's Hole at 210 feet and scooping up china plates while he hummed the theme from Indiana Jones, "and time was that great big boulder coming at you."

In '91, Crowell didn't even own a computer, but that all changed with the advent of affordable software that allowed divers to enter any combination of gases and get back a theoretically safe deco schedule for any depth. "In a matter of months, we went from rubbing sticks together to flicking a Bic, " Crowell says. It was the aggressive use of computers - and the willingness to push the limits - that separated the SEEKER from the competition. When Bill Nagle, the boat's previous captain, died of his excesses in '93, Crowell came up with the cash to buy the SEEKER. He'd made the money in the harsh world of hard-hat diving.

Picture Crowell in his impermeable commercial diver's suit, with its hose-fed air supply and screw-down lid, slowly submerging in black, freezing water at some hellish industrial waterfront wasteland. The metaphorical ball cock is stuck and somebody's gotta go down and unstick it. Hacksaw it, blast it, use a lift bag and chains - who the fuck cares how he does it? Imagine him slogging through thigh-deep toxic sludge hefting a wrench the size of a dinosaur bone. His eyes are closed and he can't see a damned thing down there anyway - and he's humming a tune to himself, working purely by touch, in three-fingered neoprene mitts. Think of him blind as a mole and you'll see why he loves the camera's eye so much, and you'll believe him when he says he's never been scared on the Andrea Doria.

"Well, maybe once, " Crowell admits. "I was diving on air and I was pretty narced, and I knew it. I started looking around and realized I had no idea where I was." He was deep inside the blacked-out maze of the wreck's interior, where every breath dislodges blinding swirls of glittering rust and silt. "But it just lasted a few seconds. When you're in those places, you're seeing things in postage-stamp-sized pieces. You need to pull back and look at the bigger picture - which is about eight and a half by eleven inches." Crowell found his way out, reconstructing his dive, as it were, page by page.

YOU'VE ALWAYS THOUGHT that the way water blurs vision is an apt symbol of a greater blurring, that of the mind in the world. Being matter, we are buried in matter - we are buried alive. This is an idea you first encountered intuitively in the stories of Edgar Allan Poe. 'Madman! Don't you see?' cries Usher, before his eponymous house crashes down on top of him. And the nameless penitent in the Pit and the Pendulum first creeps blindly around the abyss, and then confronts the razor's edge of time. He might well be looking into Gimbel's Hole and at the digital readout on his console; he is literature's first extreme deep diver, immersed in existential fear of the impossible present moment. But the diver's mask is also a miraculous extra inch of perspective; it puts you at a certain remove from reality, even as you strike a Mephistophelian bargain with physics and the physical world.

You're twelve minutes into your planned twenty-five-minute bottom time when the current suddenly kicks up. It's as if God has thrown the switch - ka-chung! - on a conveyor belt miles wide and fathoms thick. You see loose sheets of metal on the hull sucking in and blowing out, just fluttering, as if the whole wreck were breathing. If you let go, you would be whisked away into the open sea, a mote in a maelstrom. The current carries with it a brown band of bad visibility, extra cold, direly menacing. Something has begun to clang against the hull, tolling like a bell. Perhaps, topside, it has begun to blow. Keep your shit together. Control your breath. Don't fuck up. And don't dream that things might be otherwise, or it'll be the last dream you know. Otherwise? Shit ... this is it. Do something. Act. Now! You're going to have to fight your way back to the anchor line, fight to hold on for the whole sixty-five minutes of your deco. And then fight to get back into the boat, with the steel ladder rising and plunging like a cudgel. What was moments ago a piece of cake has changed in a heartbeat to a life-or-death situation.

Then you see Dan Crowell, arrowing down into Gimbel's Hole with his video camera glued to his eyes. You watch the camera light dwindle down to 200 feet, 210, then he turns right and disappears inside the wreck. Do you follow him, knowing that it is precisely that - foolish emulation - that kills divers here? Consider the case of Craig Sicola, a talented, aggressive diver. On his charter in the summer of '98, he saw the crew of the SEEKER bring up china, lots of it. He wanted china himself, and if he'd waited, he would've gotten it the easy way. Crowell offered to run a line to a known cache - no problem, china for everybody. But it wouldn't have been the same. Maybe what he wanted had less to do with plates than with status, status within an elite. He must've felt he'd worked his way up to the top of his sport only to see the pinnacle recede again. So he studied the Doria plans posted in the SEEKER's cabin and deduced where china ought to be - his china - and jumped in alone to get it. He came so close to pulling it off, too.

Dropping down into Gimbel's Hole, he found himself in the first-class foyer, where well-dressed passengers once made small talk and smoked as they waited to be called to dinner. He finessed the narrow passageway that led to the first-class dining room, a huge, curving space that spans the width of the Doria . He kicked his way across that room, playing his light off lumber piles of shattered tables. Down another corridor leading farther back toward the stern, he encountered a jumble of busted walls, which may have been a kitchen - and he found his china. He loaded up his goody bag, stirring up storms of silt as the plates came loose from the muck. He checked his time and gas supply - hurry now, hurry - and began his journey back. Only he must have missed the passage as he recrossed the dining room. Easy to do: Gain or lose a few feet in depth and you hit blank will. He would've sucked in a great gulp of gas then - you do that when you're lost; your heart goes wild. Maybe the exit is inches away at the edge of vision, or maybe you've got yourself all turned around and have killed yourself, with ten minutes to think about it.

Sicola managed to find his way out, but by then he must've been running late on his deco schedule. With no time to return to the anchor line, he unclipped his emergency ascent reel and tied a line off to the wreck. Which was when he made mistake number two. He either became entangled in the line, still too deep to stop, and had to cut himself free, or else the line broke as he ascended. Either way, he rocketed to the surface too fast and died of an embolism. Mercifully, though, right up to the last second, Sicola must have believed he was taking correct and decisive action to save himself. Which, in fact, is exactly what he was doing.

But with a margin of error so slender, you have to wonder: Where the hell does someone like Crowell get the sack to make fifty turns inside that maze? How can he swim through curtains of dangling cables, twisting through blown-out walls, choosing stairways that are now passages, and taking passages that are now like elevator shafts, one after another, as relentlessly as one of the blue sharks that school about the wreck? By progressive penetration, he has gone only as far at a time as his memory has permitted. Only now he holds in his mind a model of the ship - and he can rotate that model in his mind and orient himself toward up, down, out. He's been all the way through the Doria and out the other side, through the gash that sank her, and brought back the images. This is what it looks like; this is what you see.

But how does it feel? What's it like to know you are in a story that you will either retell a hundred times or never tell? You decide to drop down into the black hole. No, you don't decide; you just do it. Why? You just do. A little ways, to explore the wreck and your courage, what you came down here to do. What is it like? Nothing under your fins now for eighty feet but the mass and complexity of the machine on all sides - what was once luminous and magical changed to dreary chaos. Drifting down past the cables that killed John Ornsby, rusty steel lianas where a wall has collapsed. Dropping too fast now, you pump air into your BC, kick up and bash your tanks into a pipe, swing one arm, and hit a cable, rust particles raining down. You've never felt your attention so assaulted: It is everything at once, from all directions, and from inside, too. You grab the cable and hang, catching your breath - bubble and hiss, bubble and hiss. Your light, a beam of dancing motes, plays down a battered passageway, where metal steps on the left-hand wall lead to a vertical landing, then disappear behind a low, sponge-encrusted wall that was once a ceiling. That's the way inside the Doria.

There is something familiar about that tunnel, something the body knows. All your travels, your daily commutes, the brownian motion of your comings and goings in the world, straining after desires, reaching for your beloved - they've all just been an approach to this one hard turn. You can feel it, the spine arching to make the corner, a bow that shoots the arrow of time. In the final terror, with your gauges ticking and your gas running low, as dead-end leads to dead-end and the last corridor stretches out beyond time, does the mind impose its own order, seizing the confusion of busted pipes and jagged edges and forcing them into a logical grid, which you can then follow down to the bottom of the wreck and out - in a gust of light and love - through the wound in her side? Where you find yourself standing up to your waist in water, in the pit the current has gouged to be the grave of the Andrea Doria. Seagulls screech in the air as you take off your gear piece by piece and, much lightened, begin to walk back to New York across the sandy plain. And it comes as no surprise at all to look up and behold the SEEKER flying above you, sailing on clouds. On the stern deck, the divers are celebrating, like rubber-suited angels, breaking out beers and cigars, and holding up plates to be redeemed b the sun.

This story also appears as a chapter in the book

Deep Blue: Stories of Shipwreck, Sunken Treasure

and Survival ( Adrenaline Series )

by Nate Hardcastle.