Carter's Creek (2/2)

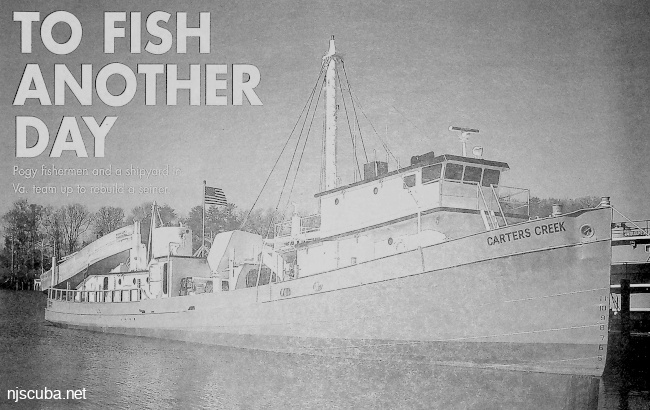

To Fish Another Day

Pogy fishermen and a shipyard in Virginia team up to rebuild a seiner

By Larry Chowning

National Fisherman

November, 2005

After a long sabbatical, a relic of the menhaden fishing industry, the 135-foot Absecon, is back doing what she was built to do - harvesting pogies. Curtis and Jimmy Kellum, Chesapeake Bay menhaden fishermen as well as father and son, are owners of Ocean Bait in Weems, Va. At Ampro Shipyard, also in Weems, they transformed the Absecon, built in 1950, into a modern day menhaden snapper, rig (see sidebar), and renamed her Carters Creek.

"When the state of Florida banned commercial gillnet and purse-net fishing, it opened up more bait markets to us and we have been able to grow," says Jimmy Kellum. As business has grown so has the need for larger boats like the Carters Creek. The Kellums sell all of their bait fish to Pride of Virginia, one of the largest bait and chum companies in the country. Pride of Virginia sells bait from Texas to Maine and has plants in Reedville, Burgess, Callao, and White Stone, all in Virginia.

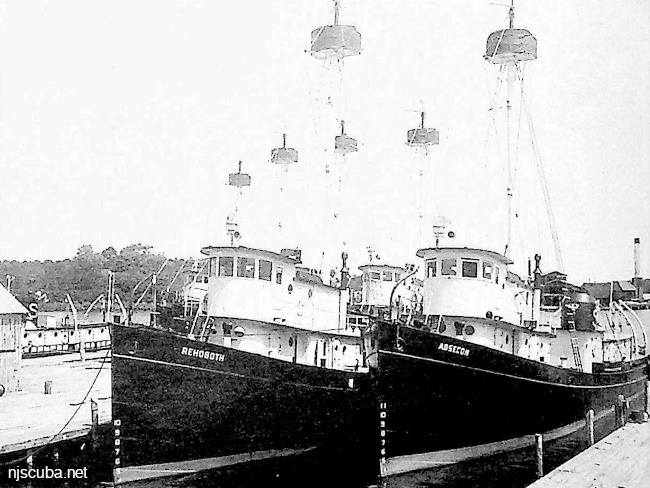

The history of the boat now called Carters Creek began in the early 20th century with the J. Howard Smith Co. of New York's Long Island. The company was one of the main players in the East Coast menhaden fishery for 63 years and built 20 new steel menhaden boats in Camden, N.J., after World War II, and the Absecon was the first.

The Absecon was in the menhaden fishery for 25 years and in 1975 was sold to American Clam Co., in Chincoteague, Va., which rigged her over to fish hard clams in the Atlantic. In the 1980s, the boat was sold to a clam fisherman who, in addition to hard clamming, used the boat to fish for horseshoe crabs. When the government placed a moratorium on horseshoe crabs, the Absecon's fishing days seemed to be over.

'Snapper Boats'

The origin of the word "snapper," as it relates to menhaden fishing, is lost to time. However, it probably has something to do with size, going back to the days when watermen first started calling immature bluefish snappers, in the same way snapper boats are smaller than company-owned menhaden boats. (Also, snapper boats are independently-operated.) The term snapper also refers to how a boat with that name is equipped, and, again, is contrasted with the larger, company-run boats.

A snapper boat has a single purse boat. As it approaches a school of fish, it drops an anchor to hold one end of the seine and then circles the fish, while feeding the net overboard. The leadline keeps the net on the bottom. By contrast, bigger company-owned boats use a pair of 40-foot purse boats that are lashed together, each carrying half of the net. After getting word from a spotter pilot, the boats break away from each other to circle the school of fish. When the boats are rejoined at the head of the circle, a lead "tom," weighing 1,000 pounds is slid down the purse line to hold the net on the bottom.

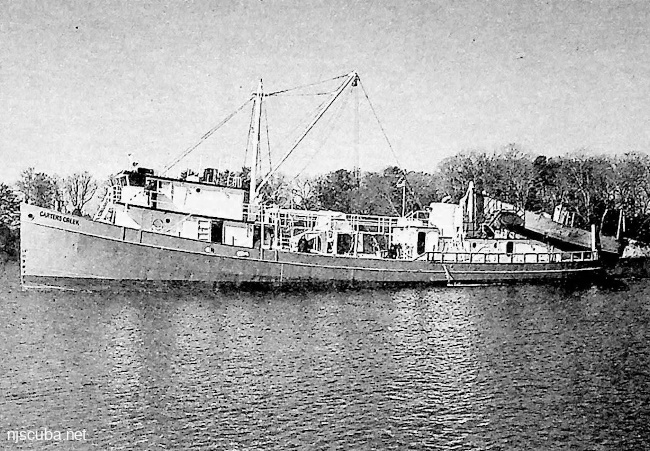

Carters Creek does not fit the traditional idea of a small boat, but it does reflect the changing times of the fishery and the need for larger boats. The 135' x 22' boat is the largest snapper rig on the bay.

- L.C.

When the Kellums found her, the Absecon had been tied up for five years alongside a riverbank near Pocomoke City, Md. The Kellums were looking for a boat that could be used in both the bay and the open ocean. The Kellums sought such versatility because they didn't want to be compelled to buy another boat to fish the Atlantic if regulators limited or cut off their operations in the Chesapeake. In addition, Jimmy, 42, wanted a boat that would take him into retirement. The Absecon fit the bill.

"We already knew right much about the boat," says Jimmy. "We knew the government conscripted right many Smith boats for the war, so after World War II the government provided high quality Cor-Ten steel to build Absecon and other Smith boats." (Cor-Ten is a "weathering" steel with exceptional abilities to resist corrosion.) Jimmy says he also knew Absecon was built off the model of a wooden menhaden steamer named the Little Joe that had been built before World War I and worked on Chesapeake Bay. She was a boat greatly admired by many in the area, he says.

"We went over to look at [the Absecon] and we couldn't believe the good condition of the frames inside of her," Jimmy says. "Still, we knew that all we were getting was a hull and an engine because all the rigging on her was from other fisheries." The American Clam Co. had re-powered the Absecon in 1978 with a Detroit Diesel 16V-149. The engine had been worked but not extensively for the past 20 years, says Jimmy.

The Kellums purchased the boat and brought it to Ampro Shipyard and the boatyard's manager, Lynn Haynie. "We got her over here and started stripping all the gear off it and I realized then what a job we really had on our hands," says Jimmy. "I told Lynn don't spend another dollar until we haul her and take an ultra-sound of the bottom." The ultrasound picked up one spot on the bottom with 10 percent deterioration and that was right over the wheel. Everywhere else, the hull's plate thickness was 3/8-inch or better. "She didn't have a patch on her bottom anywhere," Jimmy says.

A big part of early work on the boat was removing heaps of old clamming and horseshoe crab fishing gear from inside the boat and off her deck. Jimmy says, "When we brought her here she drew 8 feet, 6 inches in the bow and 10 feet in the stern. Now she draws 3 feet in the bow and 8 feet in the stern." Scrap iron amounting to 130,000 pounds was sold, and that wasn't all of it. Jimmy says, "I would say we have another 100,000 pounds of surplus equipment that came off her, such as winches, outriggers, generators, gaffs and more."

Ampro Shipyard allowed the Kellum's crew to work on the boat when they weren't fishing the Kellum's Bay Lady. What the Kellums and their crew couldn't do, Ampro could. "You don't find many yards that will work with you the way they have," says Jimmy.

Because Jimmy lives just a half-mile from the boatyard, he could easily monitor the work. "Not just anybody wants to fool with an old boat, because you don't know what you are going to run into," he says. "We couldn't afford to have someone do all the work. We've used Lynn's labor as much as we have needed it and our own as much as possible. "For a fisherman to afford a major job like this, you have to have that kind of cooperation. It has been good for the yard and good for us. We are very grateful. If Lynn needed her men for another job, they went and no questions were asked."

After five weeks removing all of the boat's old fishing gear, the rebuilding work started. The biggest job was installing bulkheads along the centerline and transversely at the stern. All of the bulkheads were 3/8-inch galvanized steel. Before the bulkheads went in, concrete and insulation in the fish hold were removed down to the bottom plating so the bulkheads could be welded in place. Air-hammers were used to break up the concrete and insulation.

Five feet of the rounded stern was cut off and replaced with a flat transom and a ramp for the purse boat. A new M-12 Pullmaster winch lowers and hauls the purse boat up the ramp. An innovative feature on the Carters Creek is the catwalk between the forward and aft houses, which allows the crew to move from one to the other without having to climb up and down ladders. "The Omega [Protein, a menhaden company] captains are kidding us that we have created a real problem because their crews want that feature too," says Jimmy.

The boat's hull plating might have been in good shape, but a lot of topsides steel had to be replaced. All the 36-inch hatch coamings were torn out and rebuilt with 3/8-inch steel. Three-quarters of the steel deck was removed and new 1/4-inch steel laid down. And most of the steel flooring in the house and galley was cut out and replaced with 1/4-inch steel. The galley also got new doors.

There wasn't any life left in the round, narrow wheelhouse. When it was hoisted up, anywhere there was black iron "it was ate up," Jimmy says. "Everyone had an opinion on how to build the wheelhouse. It had to be redone because it was rotten. Some wanted to leave it round. Some wanted it square and some wanted it square with rounded corners."

Jimmy took a camera over to the Omega Protein docks near Reedville and took photos of the cabin on the menhaden boat Shearwater. Because Jimmy liked the style, he duplicated the square shape of the corners on the Carters Creek. Jimmy says the biggest job was rewiring the boat. "We took every sprig of wiring off and spent $67,000 to have it completely rewired." Four 200-amp services were installed.

One of the Absecon's old generators was rebuilt, and then a new 75-kW generator, running off a rebuilt 6-71 Detroit, was installed. Some refrigeration equipment was pulled off the Bay Lady and installed in the Carters Creek. In addition, three new Wescold chillers came from Seattle, and four refrigerated sea water 4" x 3" circulating pumps were installed. Three new Puretic winches to haul the purse net up were mounted on the deck. A 10-inch Universal fish pump for moving fish from the net into the Carters Creek fish hold came off the Bay Lady. A rebuilt 4-71 Detroit Diesel powers the pump.

As part of the retooling and restoring of Carters Creek, Jimmy installed a horn his grandfather had used on the menhaden steamer Raymond Humphreys. During sea trials, Carters Creek did 13.2 knots and 12.9 coming back. "We think the new wheel would move her about 14.5 knots," Jimmy says. "When we got her we weren't sure about the engine but it turned out good."

Carters Creek hasn't turned out so bad, either. The boat now fishes Cheseapeake Bay, showing an old boat can come back to life if the right people come along.

Larry Chowning is a reporter for the Southside Sentinel in Urbanna Va.

Article courtesy of Deltaville Maritime Museum

258419

Questions or Inquiries?

Just want to say Hello? Sign the .