How to Make a Reef

Building artificial reefs is a lot more than just throwing junk in the ocean. The material needs to meet standards for cleanness and suitability, and it needs to end up where it is intended, and not somewhere else. Concrete and stone are easy, as they go straight down wherever they are dropped.

went to pieces within months

The stainless-steel 'Brightliners' were expected to last for 25-30 years. Fortunately, the program was aborted before too many of them were reefed, and rolling-stock is no longer considered suitable reef material. It seemed like a good idea at the time ...

Army tanks have been used with great success, as long as they are placed on a hard-enough bottom to support their weight. Maryland dropped tanks on a mud bottom, and they disappeared in short order.

The problem with military vehicles is that they usually require a great deal of cleaning before they can be sunk. If the Army didn't do it themselves, the cost would be prohibitive. Such vehicles are interesting, but really too small and few to be important.

This is a side-scan sonar image of many overlapping barge-loads of rock dredged from the bottom of New York Harbor. The specialized barge opens its bottom and drops the rock right out. These are on the Sandy Hook reef.

While rock and concrete last forever, they do slowly sink into the bottom. Simply dropping more on top takes care of that problem; between New York and Philadelphia, the supply is inexhaustible.

One reef material that has been disastrous at times has been automobile tires. Underwater, rubber lasts forever, but not so the materials used to bind the tires into 'tire units'. When these break apart, the tires roll around the bottom, and it's just a mess, as they are not heavy enough to sink in and disappear. Only very large heavy earth-mover tires are suitable at all, and nowadays rubber tires of any kind are not used for artificial reefs.

Floatables must be avoided. For example, when the old wood fishing schooner American was sunk, the hull stayed down, but the masts popped out of their sockets and floated away and had to be retrieved. Wood boats are no longer used as reef subjects; they don't last long anyway. Fiberglass is no better.

However, vessels of all kinds are really the jewel in the crown of any artificial reef program. The goal in sinking a ship is to get it upright in approximately the place you want it. That means mooring it in some way, and then flooding it so it goes down on an even keel. Once you get it sunk right, a steel ship can have a useful life as an artificial reef for 30-50 years or longer.

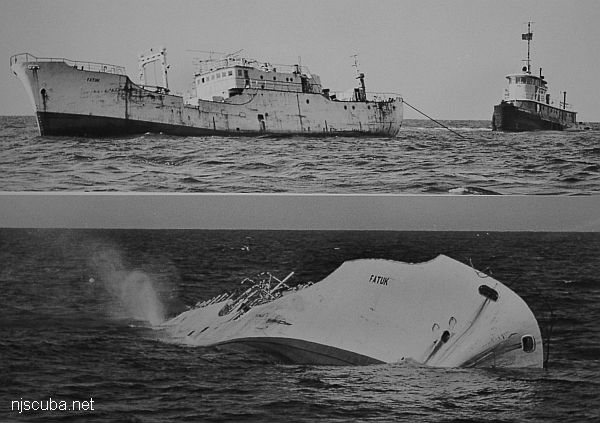

Sometimes, things don't go as planned - the Onondaga flips over - 1993

It is important to make sure the vessel is not top-heavy, as once it sinks it loses any stability it had at the surface and could flip over before it hits the bottom. Even a flat-bottomed deck barge can flip over if it is overloaded. This page seems like a compendium of artificial reef mistakes, and it is. Making mistakes is how you learn, and a lot of this had never been done before. The bad thing is not making a mistake, but making the same mistake twice.

This is one reason why emptied-out tugboats and trawlers make such great reef subjects - with their heavily-constructed hulls, no matter how crooked they seem to go down, they always right themselves on the bottom. The same is not true for trawlers that sink 'naturally' - many of those do end up upside-down because overloading is often the cause of the sinking in the first place.

So how do you fill a ship up with water so it sinks?

with explosives !!! The Algol - 1991

As far as I'm concerned, this is the best way to make a reef. The Navy used to use these sinkings as training for their demolitions people, free-of-charge. But sadly it is no longer politically correct and hasn't been done in years. Even the enormous USS Radford (2011) was quietly scuttled without the benefits of modern chemistry. A warship should have gone out with a bang, not a whimper.

Then how do you sink a ship if you can't blow it up properly? Well, here's the wrong way: the Steven McAllister (2000) was sunk just by opening her sea-cocks. It took hours and hours, and hours, and hours. And hours. It took a long time. Everyone was exhausted just from waiting, and ravenous as every last crumb on the boat got eaten, and some of the woodwork as well.

The crew of the Mary L McAllister even tried hosing water into the wreck to speed things up. Too bad they didn't have a real fire-fighting hose, that might have actually helped.

Finally, moments before sinking, the Mary L untied and moved away. And then - BLOOP! - as soon as the water topped the back rail, the Steven sank so fast, I didn't even get a picture.

We were planning to dive the new reef right away, but by the time it finally went under, everyone just wanted to go home. And the Steven McAllister was not the only time I endured a debacle like this, the Captain Bill above took over four hours to sink by seacocks. The assisting tug even tried bumping and 'waking' it, but nothing helped.

There has to be a better way, and it turns out there is.

In the picture above, you can see three rectangular tan patches that are weakly welded over three holes that were cut in the hull above the (new) waterline. There are three matching ones on the other side. They are located to open up any compartments inside the hull. This allows the boat to be seaworthy enough to be towed out to the reef site. Inside, any watertight bulkheads have been similarly holed for even flooding.

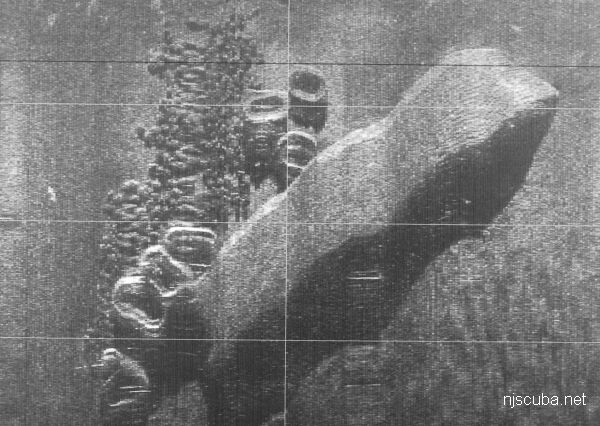

In the next picture, you can see the patches have been knocked out from inside with a sledgehammer. Then the seacocks are opened to start the flooding process. Flooding by seacock is slow, sometimes water is also pumped in from a supporting vessel. Wave action can also help.

Once the first hole reaches the waterline, the process accelerates greatly. The holes can also act as air vents once the hull starts flooding really fast over the rail. Knocking out the patches is a safe enough job though - the ship is not going to sink right away. In the video of the Radford above, you can see enormous holes being cut in the hull for the same reason.

This system works very well, but I still prefer explosives.

So that covers how to sink a ship. But what about holding it in place while it sinks? You can't have it drift away, and you don't want to use an anchor - those are expensive. If you expect a quick sinking, you can hold the new reef in place with the attending vessel, but as we've seen - there is no guarantee of a quick sinking.

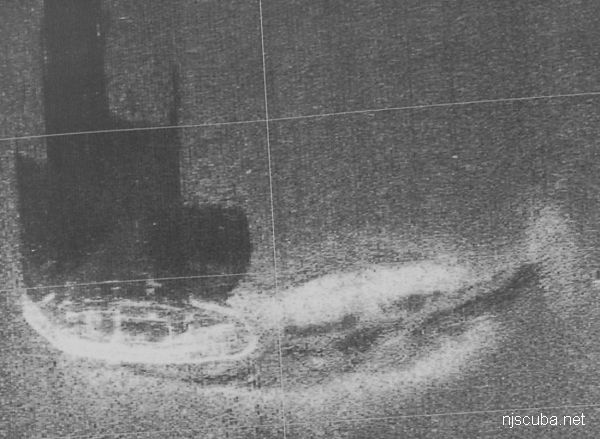

The solution can be seen in the picture below:

You can see a tight hawser holding the block up in the frame, and a loose one below it to hold the ship when the block is released. The block is an old buoy mooring, with an old hawser attached - just enough to hold the ship in place on a nice day for the short time until it hits the bottom. Cheap and cheerful! It looks like the frame was welded together from pieces cut off the rest of the ship.

So that's it - now you can start your own artificial reef program! You'll just have to learn to deal with obstructive bureaucrats on every level from local to federal, plus wacko environmentalists, and selfish commercial fishermen. ( OK, they're not all obstructive, and wacko, and selfish. But enough are. )