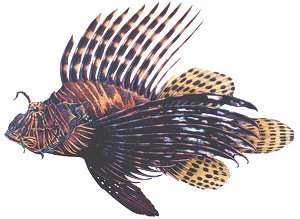

Lionfish

Pterois volitans

Size: to 17", usually smaller

Habitat: turning up all along the East Coast

Notes: venomous spines

This Indo-Pacific scorpionfish has been sighted in the wild in Florida and the Caribbean since the 1990s. In 2000 it began appearing off North Carolina. Two juveniles were found off Long Island in 2002, and in 2003 a two-inch yearling was collected in the Shark River. Of course, this popular pet is sighted daily in public and private aquariums all over the world.

The presence of immature individuals is a sure sign that a breeding population has become established in the Atlantic. How these fishes got here is not clear, but they are probably the descendants of released and escaped pets. It is thought that a large number of them escaped captivity in Florida during Hurricane Andrew. The other possibility is that they were transported here in the bilge water of a ship or transited the Panama Canal, but both of these are highly unlikely.

The northern extent of this fish is unknown. The few individuals found so far are almost certainly strays, like the other tropical fishes listed here. However, Lionfish are found in quite cool waters in the Pacific, and as the population grows and adapts, it may spread northward. These fishes seem to be able to overwinter in North Carolina. Whether or not they can breed there is not yet known. And while it may turn out that they can overwinter even here, I doubt they can successfully reproduce in our cold waters.

Lionfish are slow-moving and unaggressive. The wasp-like sting of the venomous spines in the dorsal and anal fins is painful but not dangerous to humans. Cold-water gloves and exposure suit should be more than enough protection for a northern diver. What next, sea snakes?

The public is encouraged to report all lionfish sightings and collections to Paula Whitfield at the NOAA Beaufort Laboratory, (252) 728-8714 or by e-mail: paula.whitfield@noaa.gov.

Lionfish Roar into the Atlantic

A non-native could trouble the waters around LI

By Joe Haberstroh

Staff Writer, Newsday, Inc

September 7, 2003

Venomous visitors from the west have been turning up in local waters, and they're not particularly welcome. They're lionfish -- a species from the Pacific and Indian oceans bristling with toxin-filled spines. Highly aggressive, lionfish are a non-native aquatic species that has biologists concerned about the impact they might have on the fish that have always lived around here. The concern started in Florida and the Carolinas (where lionfish were first seen) and has slowly spread north.

Todd Gardner, an aquarist with Atlantis Marine World Aquarium in Riverhead, collected three of the unusual fish late last month in Shinnecock Bay. Three years ago, Gardner caught two lionfish in Fire Island Inlet, the first lionfish documented in New York state.

Lionfish are visually stunning, with dark red and white bands covering head and body. They have a series of poisonous dorsal spines along the top of their bodies and feather-like pectoral fins around their sides and underneath.

The fish Gardner caught recently measured one to two inches long, but a fully grown lionfish can be 15 inches long. With all the long spines and fins, the fish can appear to be as big as a soccer ball.

Lionfish use their spines primarily for defense. The spines are living hypodermic needles that can release toxin through their tips. Although the fish's venom apparently is not fatal to human beings, people who have grabbed the fish have ended up in the hospital for weeks. "I've been spined a couple of times by a lionfish -- by a single spine, and it was very painful, " Gardner said.

When courting a female, male lionfish use their spines to defend territory and ward off rival suitors, said Paula Whitfield, a biologist with a laboratory in Beaufort, N.C., operated by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. "They have been observed in an aquarium fighting with their spines."

Taking a long route to get here, lionfish larvae probably bobbed along to the Northeast in the off-shore jet stream and were blown landward in one of the eddies that break away from the main current. In just this way, certain damselfish, groupers, and other tropical species arrive to make summer homes in Long Island bays. None of these fish apparently survives the cold winter temperatures here.

Many observers date the appearance of the outsiders on the East Coast to shortly after Hurricane Andrew in 1992 when homeowners dumped tropical fish from aquariums into the ocean. Scientists also believe lionfish could have traveled to the Atlantic in ballast water carried in the bellies of giant transport ships and dumped at the ship's destination.

Biologists and regulators are keenly interested in whether lionfish are reproducing in U.S. waters. One study, which indicates that this is the case, found just two lionfish after surveying several locations off the North Carolina coast in August 2000. Two years later, 49 lionfish were sighted in 16 locations. The fact that the Shinnecock Bay lionfish are juveniles suggests that the fish are successfully breeding. After Gardner's find, more lionfish were netted off Belmar, N.J.

They may be surviving because no other fish here is known to kill it. A wild animal without predators is in a position to dominate. Biologists worry that lionfish could reduce the population of Atlantic fishes unaccustomed to its sting. Even the small lionfish he has captured had "bellies full" of juvenile species of local fish, including cunners, blackfish, and silversides, Gardner said. "The scary thing about them being here is that they are not a native species, and they have no known predators in the Atlantic Ocean, " he said.

Whitfield adds, "The concern is that we really don't know what's going to happen. We really cannot predict the impact of invasive species, and when we finally begin to understand the impact, it's really too late to do anything about it. We're thinking that lionfish, at least in the Southeast, are probably here to stay."

Neither Whitfield nor Gardner offers a comparably bleak scenario for Long Island waters. The best lionfish can do is to establish themselves here only during the summer and early fall when the waters are warm. The question will be, for a few months each year without natural predators, how much damage can they do?