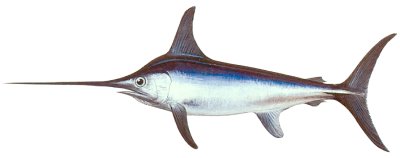

Broadbill Swordfish

Xiphias gladius

Profile by Bill Figley

Fisheries Biologist

Range and Habitat:

Swordfish are found in temperate and tropical waters. On the East Coast, they extend from the Caribbean to Newfoundland. They occur in New Jersey waters almost year-round but are most abundant from July to October. Swordfish are pelagic, occurring in the open ocean in depths of over 300 fathoms. They prefer waters 55-65°F. During the summer they concentrate along the edge of the continental shelf but move further offshore to the warm Gulf Stream during the winter. Although swordfish are often seen basking on the surface, they spend most of their time deep in the water column.

Size:

Off New Jersey. swordfish average 100-200 lbs., although they may exceed 1,200 lbs and 15 feet. The males are much smaller than the females and seldom exceed 200 lbs.

Food:

Squid, mackerel, hake, deep-sea fishes.

Spawning:

In winter, swordfish migrate to the tropical waters of the Caribbean to spawn. Females are very prolific, carrying up to 16 million eggs. Young swordfish have teeth and scales, but these are lost by the time the fish reach 10 lbs. in weight.

Recreational and Commercial Importance:

In New Jersey, commercial fishing for swordfish began in the 1960s. Longlines are the primary gear used to harvest swordfish, although harpoons are also used on occasion. The catch quickly rose to a peak of one million pounds in 1965, before dropping precipitously due to national hysteria over high levels of mercury found in swordfish flesh. Restrictions on inter-state sale of swordfish were imposed by the Food and Drug Administration. Eventually, the ban was relaxed and the commercial fishery resumed.

Although very few swordfish are caught by sport fishermen in New Jersey, they are considered one of the ultimate gamefishes. [ Overfishing by commercial longliners ( as in "The Perfect Storm" ) has made large Swordfish scarce. ]

Sportfishing Facts and Techniques:

Anglers catch swordfish in two ways, either by the traditional method of trolling around fish spotted finning on the surface or by the recently devised technique of drifting rigged baits at night. Overall, night drifting appears more productive.

The swordfishing grounds along the New Jersey coast lie off the edge of the continental shelf in depths of 300 to 1,200 fathoms. The mouths of the canyons are particularly productive. Most night drifting for swordfish is combined with daylight trolling for tuna and marlin. Toward dusk, anglers position their boats so that prevailing winds will push them along a particular fathom contour or predetermined route for the night's fishing.

Heavy-duty, high-quality equipment is the rule ( 5/0 to 9/0 reels, matching rods, 50 to 80 lbs. test line, ball bearing swivels, 8/0 to 12/0 hooks. ) Whole or cut baits of squid, mackerel, bonito, or skipjack are rigged on 12-foot leaders of 200 to 300 lb. test mono. A chemical light stick is either attached directly to the snap swivel or with light, break-away line. The glow of the light stick attracts swordfish to the bait. Usually, three baits are set out at various depths, between 20 and 150 feet from the surface. A trolling weight can be used to hold the baits down on a fast drift.

Swordfish often pick up bait very slowly, mouthing it for a long time before swallowing It and finally moving off. Anglers must be patient arid wait for the fish to run off at a hard pace before setting the hook.

Acknowledgments:

Anthony Hillman (art), Migdalski and Fichter (1976) McClane (1978), IGFA (1979), Pete Barrett.

This article first appeared in New Jersey Outdoors - September / October 1983