Blackfish (1/2)

Tautoga onitis

Profile by Peter J. Himchak

Supervising Biologist,

Marine Fisheries

Range:

Tautog are distributed along the northeast Atlantic coast of North America from the outer coast of Nova Scotia to Georgia. Greatest abundances are found from Cape Cod to the Chesapeake Bay. North of Cape Cod, they are usually found close to shore ( within 4 miles ) in water less than 60 feet deep. South of Cape Cod, they can be found up to 40 miles offshore and at depths up to 120 feet.

| Length ( inches ) 3.0 5.5 9.0 10.5 12.5 14.0 15.5 17.0 18.0 19.0 21.0 22.0 | Age ( years ) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 15 20 |

Size:

The Tautog is a slow-growing, long-lived species with individuals over 30 years of age having been reported. Larval growth rates have been estimated to be between 0.01 and 0.03 inches per day. Young of the year juveniles grow during the summer at a rate of around 0.02 inches per day. Juvenile growth rates have been observed to be higher in vegetated than in unvegetated habitats. Average length after the first summer of growth is 2.9 inches; 6.1 inches after the second summer of growth. Adult growth is relatively slow and varies with the season. Adult male tautog grow faster in length than adult females. A reasonably accurate guide to tautog length at age is provided in the table to the right.

Food & Feeding:

Juvenile tautog feed primarily on small bottom and water column invertebrates. Diet changes as juveniles mature and increase in size. Adults feed primarily on the blue mussel and other shellfish. Adults grasp mussels using their large canine teeth, tearing them from the surrounding surface by shaking their heads. Small mussels are swallowed whole, while large, hard-shelled ones are crushed by the pharyngeal teeth prior to swallowing. Adult tautog also consume barnacles, crabs, hermit crabs, sand dollars, scallops, and other invertebrates.

Migration:

Tautog are not highly migratory along the Atlantic coast but rather demonstrate an inshore offshore migration pattern throughout the year. Adult tautog migrate inshore in the spring as the water warms to around 48°F to spawn in late spring through early summer. The fall offshore migration is triggered when water temperatures drop below 52°F in the late fall. Most adult tautog form schools and migrate offshore to deep water locations ( 80-150 feet ) with rugged bottom, becoming inactive throughout the winter.

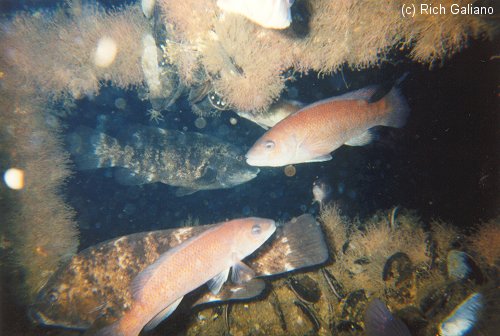

Habitat:

Tautog are structure dependent fishes throughout their lives. Juvenile tautog occur in bays, in submerged aquatic vegetation beds, and around pilings or other hard structures. Adults inhabit rough bottom, which includes rock outcroppings, shipwrecks, and artificial reefs, in near-shore ocean waters. North of Long Island, NY, rocks, and boulders can be found in abundance along the coastline as a result of glacial deposition, providing habitat for larger tautog. South of Long Island, there are a few natural rocky habitats in coastal waters, so tautog commonly inhabit shellfish beds, coastal jetties, pilings, shipwrecks and artificial reefs. The major rock outcroppings along the New Jersey coast occur off the mouth of Delaware Bay and the area north of Manasquan Inlet. Artificial reef locations occur along the entire New Jersey coastline. Artificial reef creation may be expanding tautog habitat into open, sandy coastal areas where tautog would not normally be found.

Spawning:

Tautog normally reach sexual maturity at 3 to 4 years of age ( 7-12 inches ). Spawning usually occurs within estuaries or in near-shore marine waters. Tagging studies have shown that adults returned to the same spawning locations over a period of several years. Discrete spawning groups may exist in Narragansett Bay, Long Island Sound and Chesapeake Bay as evidence by tagging studies and fishing observations. Optimum size for female egg production has been estimated at 16 inches. Tautog between 8 and 27 inches in total length were observed to contain 5,000 to 637,500 mature eggs. Eggs are buoyant without oil globules, 0.9-1.0 mm in diameter. Spawning occurs in heterosexual pairs or in groups of a single female with several males.

World Record

Caught in NJ

Recreational and Commercial Importance:

The primary fishing grounds extend from the beach out to about the 12 fathom contour. Recreational fishing modes include bottom fishing, particularly the directed trips of party and charter boats, jetty fishing, and spearfishing. The tautog is fished recreationally during April-June and September-December. The ideal boat rod for tautog is 7 feet in length with a sturdy butt section and slow tapered tip. Live green crabs or fiddlers are the best bait to use. Conventional reels are preferable over spinning tackle for bottom fishing and a fishing rod with muscle will help keep those hooked tautog from getting back into the reef structure where the line may get hung up or cut on the sharp edges of mussels or barnacles. The mean weight of tautog harvested in the New Jersey recreational fishery ranges from 1.8 to 2.3 pounds. The New Jersey State record tautog weighed 21 pounds 8 ounces. New Jersey recreational landings have fluctuated over time ranging from 0.2 million pounds in 1981 to the peak value of 2.5 million pounds in 1992.

Commercial fishery landings for tautog in New Jersey averaged 108,000 pounds over the period 1981 through 1994, coming from a variety of gear. Presently, fish pot trawls account for most of the commercial landings. Historically, commercial landings have accounted for approximately 10% of the New Jersey total annual tautog harvest.

Acknowledgments & References:

Illustration and feeding, Bigelow and Schroeder (1953); range, Parker, et al. (1994); larval growth, Dort (1994); young of year growth, Sogard, et al. (1992); adult growth, Cooper (1967), Simpson (1989), Hostetter and Monroe (1993); feeding, Olla, et al. (1974); spawning, Sogard, et al. (1992); tagging, Cooper (1966), Lynch (1991); fecundity, Chenoweth (1963); fishing tackle and illustration, Freel (1989), Public Information Document and Tautog Fishery Management Plan, ASMFC (1995, 1996).

This article first appeared in New Jersey Reef News - 1998 edition

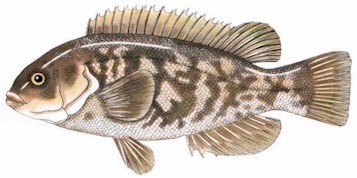

Older individuals like this one acquire an overall gray coloration, with white patches on the sides. They also develop grotesque thick fat lips, and a mean snaggly set of teeth, although they will not try to use them on you.

Blackfish are usually taken by spear, but the really big ones tend to be extremely wary and difficult to approach - they didn't get big by being stupid! Hunting them is worth the effort, the flesh is firm and white, is excellent fried, baked, or in chowder.

The hide of a Blackfish is thick and tough, almost like leather. When cleaning your catch, I have found that it is easier to fillet the fish first, then pull the skin from the fillets, scales and all, using pliers! Trying to scale one of these beasts with a knife just results in a dull knife, and the skin imparts a fishy taste that ruins the meat if not quickly removed.

I must question the logic of the fishing regulations for this species, at least with regards to offshore fishing in deep water. A hook-and-line fisherman might haul up dozens of "shorts" from the bottom to the surface, looking for that one keeper ( in fact, the current laws encourage them to do this ). Although these little fish must be released, the damage is already done - their swim bladders expand just as our lungs would in an uncontrolled ascent, with even worse effects. Often the internal organs are forced out through the anus. The fish also suffer a temperature shock from being pulled through the thermocline, not to mention whatever harm the hook itself has done to them. Although they may swim away into the depths when set free, I sincerely doubt very many of these poor fish survive. This does not seem like a very good conservation plan to me. At least a spear-fishing diver can verify the size and status of his quarry before taking it.

When it gets cold, Blackfish move to their offshore wintering grounds and become inactive. Baby Blackfish look just like adults, except they may be emerald green, the better to hide amongst the weeds. They are shy and retiring.

Tautog was the Native American name for the fish.