United States Coast Guard 2 (6/7)

Search and Rescue

Ever since man has gone down to the sea in ships, great risks have been run to rescue those in danger. To improve the possibility of success, responsibility had to be delineated and means appropriated. In 1831 the Secretary of the Treasury directed the revenue cutter Gallatin to cruise the coast in search of persons in distress. This was the first time a government agency was tasked specifically to search for those who might be in danger. In 1837 Congress authorized the President "to cause ... public vessels ... to cruise upon the coast, in the severe portion of the season ... to afford such aid to distressed navigators as their circumstance and necessities may require; and such public vessels shall go to sea prepared fully to render such assistance." This addressed rescue on the high seas. Yet, during the age of wood and sail, most disasters occurred close in to shore.

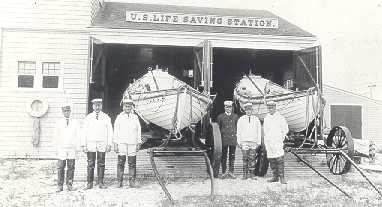

Right: the Salisbury Beach, Maryland, Life-Saving Station, crew, and surfboats, circa 1900

From colonial days, the coastal colonies, later states, had certain responsibilities for the salvage of goods tossed upon their beaches from shipwrecks. Many states also imposed upon the salvagers the duty to rescue persons on board shipwrecked vessels as a prerequisite to obtaining salvage rights. Persons appointed by the states, called "wreckmasters, " "commissioners of vendue, " "commissioners of wrecks, " etc., were specifically charged with assembling a volunteer boat crew at each wreck that occurred within the wreckmaster's jurisdiction for the purpose of rescue and salvage. These early efforts were closely tied to maritime interests at the large coastal ports of Boston, New York, and Philadelphia.

The middle of the 19th Century was the era of the immigration packet. Small sailing ships were packed with several hundred immigrants in Europe. As these ships neared New York, nor'easters, which prevailed in the winter months, drove many of the crowded vessels aground on the New Jersey shore. There, but a few hundred yards from safety, the surf would pound the sturdiest craft to pieces and the freezing, tumultuous water would overcome the strongest swimmer. Many rescue attempts were made from shore under these circumstances but, on average, only about half those people on board reached the beach alive. The losses were not for a lack of volunteers wishing to help but mostly because no means had yet been contrived to reach the wreck across the breaking surf and to retrieve the occupants of the stricken vessel.

An innovative solution was needed; techniques and equipment had to be developed in order to save those stranded so close to their new homeland. Beginning in 1848, a federal lifesaving service began to take shape. At first, the government provided a garage-like structure outfitted with rescue equipment. The coasts of New Jersey and Long Island had experienced the greatest numbers of wrecks with the result that these beaches were the sites for the new stations. The construction and equipping was a joint project carried out by a Revenue Marine officer, the boards of underwriters, and local citizens associated with salvage work. There was a fully-equipped iron boat on a wagon, a mortar apparatus for propelling a rescue line, powder and shot, a small covered "life car" for hauling in survivors, a stove, and fuel. The keys to the station were entrusted to a community leader, usually a wreckmaster, and he organized his volunteer crew.

There were successes - in 1850 the immigrant ship Ayrshire grounded during a snowstorm at Squan Beach, NJ. Under the supervision of wreckmaster John Maxon, the volunteers rescued 201 of the 202 persons on board. There also were failures. During the Civil War, all save one of the iron surfboats were commandeered for use in the Hatteras Campaign. The remaining one was being used to slop hogs. Nevertheless, over the period 1848 through 1870 about 90% of the persons onboard vessels wrecked within the scope of this Life-Saving Service survived.

Following the war, in 1871, the Life-Saving Service was "reborn" under the leadership of Sumner L. Kimball (right), ably assisted by Revenue Marine Captain John Faunce (who had commanded Harriet Lane at Charleston in 1861). New stations were built; new equipment was developed; the scope of the Service was expanded beyond New Jersey and Long Island and personnel were federalized.

Much of the equipment and techniques developed during the mid-1800s continued in use for a century. The Lyle Gun (below right), named for an Army captain, David A. Lyle, who devised it, typifies this. This weapon of salvation was used to throw a line from the shore to a distressed ship.

Officers from the Revenue Marine played an important part in the operations of the Life-Saving Service. Each Life-Saving Service District was assigned an Assistant Inspector, usually a first or second lieutenant, who reported to a Revenue Marine captain. He was assigned as the full-time Inspector of the Life-Saving Service. The inspectors performed training and administrative inspections and conducted investigations in instances where lives were lost during shipwrecks.

In September 1888 the crew of Hunniwells Beach Station rescued fifteen persons from Glovers Rock in Maine. They had to lash the Lyle Gun on the after-thwart of their lifeboat and set the shotline box on the stern. The gun was loaded with a one-ounce cartridge of powder, and fired, casting the line almost into the hands of those in danger. Removing the people by breeches buoy was impossible due to the rocks; a small dory was rigged instead, and the fifteen people were hauled to safety. During the same storm, the crew of the Lewes (Delaware) Station, fired their gun from the upper window of a fish house, and landed the crew of the distressed craft in the loft with a breeches buoy.

Crews had to be able to perform their duties in the dark. On 3 February 1880, a storm wrought ruin upon the Jersey coast. At the height of the tempest, in the dead of night, Life-Saving crews rescued, without loss of life, the people of four ships. The beach apparatus was set up and worked in almost total darkness; the lanterns were thickly coated with sleet and were practically useless. The records of the Life-Saving Service are crowded with similar rescues.

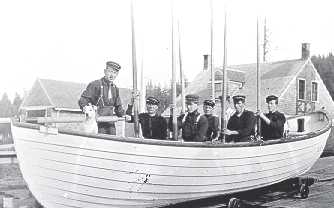

Right: the crew of the Neah Bay Life-Saving Station, circa 1910

The schooners Robert Wallace and David Wallace were wrecked at Marquette, Michigan on 18 November 1886. The Ship Canal Station crew traveled 110 miles by special train and rescued the ships' crews. In three days' work on the Delaware Coast, 10-12 September 1889, the life-saving crews at Lewes, Henlopen, and Rehoboth Beach Stations helped 22 vessels and saved 39 persons by boat and 155 by breeches buoy without losing a single life. The British schooner H. P. Kirkham was wrecked on Rose & Crown Shoal on 2 January 1892. The crew of seven was rescued after 15 hours exposure. The life-saving crew was at sea in an open boat without food for 23 hours. There also were sacrifices. Seven surfmen lost their lives going to the aid of the Italian ship Nuova Ottavia on 1 March 1876.

Personnel from the Lighthouse Service and the Revenue Cutter Service also performed heroic rescues. On 31 December 1839, the schooner Deposit was driven onto the Massachusetts coast by hurricane winds. T.S. Greenwood, keeper of the Ipswick Lighthouse, tied a line around his waist and swam through the roaring surf to the doomed ship. He then pulled a surfboat with a colleague in it to Deposit and the pair rescued the wife of the ship's captain. In 1897-1898, crew members of the cutter Bear drove a herd of reindeer 2,000 miles as food for 97 starving whalers caught in the Arctic ice.

Right: Surfman Rasmus Midgett single-handedly rescued the crew of the wrecked Priscilla

The beneficiary of search and rescue operations continually changed. From 1830 through 1870, the immigrant packet proved to be the most vulnerable. The introduction of steel, steam, and improved aids to navigation significantly reduced coastal disasters affecting large passenger vessels. These innovations introduced more shipping into the high seas, resulting in a shift in the area of operation for search and rescue activity involving vessels with large numbers of persons on board. Smaller coastal sailing vessels remained as the primary focal point for Life-Saving Service operations until the turn of the century.

From 1871 to 1914, 178,741 persons received the services of the "Life-Savers." Although some of these people faced minimal risk, only 1,455 individuals lost their lives while exposed within the scope of Life-Saving Service jurisdiction.

"Blue water" cutters, joined by flying amphibians in the 1930s, became primary rescue platforms. Regular trans-Atlantic air traffic was initiated just before World War II, introducing new clientele. Ocean Stations were established, first in the Atlantic and later in the Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific. A cutter was stationed in mid-ocean to provide rescue sites and to report on weather. Increased aircraft reliability and improved electronics have removed the need for the stations and the last was disestablished in 1977.

"Search and Rescue" has been dramatically influenced by technology from that day in 1831 when the federal government assumed a responsibility. Ironically, during World War II the Coast Guard was charged with developing the helicopter for anti-submarine warfare. The Coast Guard trained all helicopter pilots, both British and American. As the submarine threat abated in 1944, the emphasis of helicopter development was changed from anti-submarine warfare to search and rescue.

Right: a 44-MLB

Following World War II, the search and rescue scene shifted back to the tidewater, the new patron being the boating enthusiast. Pleasure craft grew in increasing numbers and the helicopter emerged as a primary rescue tool. Each era has required new equipment suited to the needs of that day.

High-seas search and rescue has long presented the Coast Guard with one of its greatest challenges. When disaster occurs, hundreds of lives may be at stake. On 14 and 15 October 1947, 69 survivors were rescued by the crew of the USCGC Bibb from the flying boat Bermuda Sky Queen, waterborne in the North Atlantic Ocean, approximately midway between Labrador, Canada and Ireland. In October 1980, while almost 200 miles off Sitka, the Dutch cruise ship Prinsendam (right) was jarred by explosions and stopped dead in the water after a fire started in the engine room. In spite of rough seas and strong winds, four Coast Guard, one Air Force and two Canadian helicopters plucked more than 500 shipwreck survivors from crowded lifeboats in the cold Gulf of Alaska. Many of the survivors, mostly senior citizens, were lifted in rescue baskets to the awaiting Coast Guard Cutter Boutwell and the commercial tanker Williamsburgh. Not one life was lost; Prinsendam sank seven days later.

Left, during Operation Able Vigil

Right, during Operation Able Manner

The 1980s and 1990s saw the US Coast Guard saved thousands responding to numerous refugee boatlifts from Haiti and Cuba. On November 24, 1995, for example, Dauntless rescued 578 migrants from a grossly overloaded 75-foot coastal freighter, the largest number of migrants rescued from a single vessel in Coast Guard history. This work has continued into the new century, for example in the year 2000 alone, the Coast Guard sortied 57,697 times and saved 3,400 lives.