Artificial Reefs Ecology

Eat or Be Eaten:

Survival of the Fittest on an Artificial Reef

The classical, textbook version of a typical marine food chain is a link-by-link progression from plankton to sardine to mackerel to tuna. If only adult life stages are considered, then this straightforward illustration has merit. In actuality, however, predator-prey relationships in the ocean are very diverse and very complicated.

When it comes to food, most fish and other marine life are very opportunistic- they eat what is available at the time and suitable to their feeding approach ( mouth size, teeth, etc. ) Big things eat smaller things and, since almost all marine species begin life as microscopic larvae, few are spared the gauntlet of hungry adversaries that come in every form and size and must likewise eat to grow bigger. In nature, it's eat or be eaten.

The rate of attrition is horrific, almost complete. Only the rarest individual, through a combination of adaptation and luck - mostly luck - survives from larva to adult. For each survivor, countless others must perish, consumed.

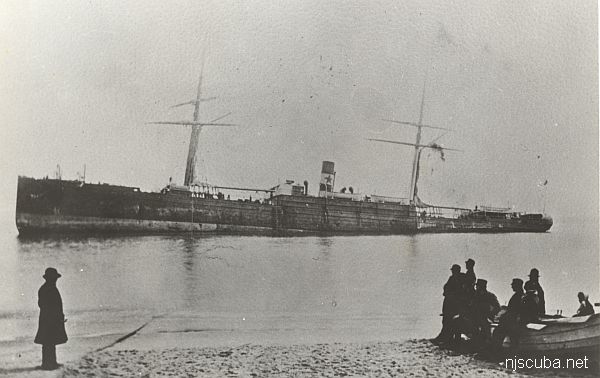

The man-made reefs along the New Jersey coast, constructed of rock, concrete, ships, and other structures, are colonized by their own special, thriving marine life communities. The healthy biota concentrated on, in, around, and over these hard-substrate habitats have a healthy appetite, too - an appetite that we are only beginning to understand.

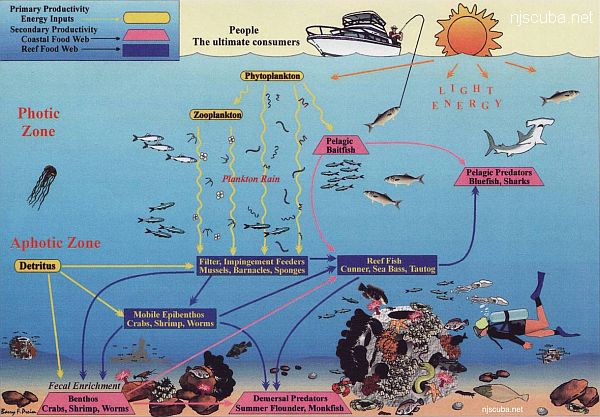

In the sea, plants using energy derived from sunlight convert carbon dioxide gas, water, and nutrients into living tissue. Plants are called producers since they make their own food. The rate at which they do this is called primary productivity. Producers comprise the basic building blocks of the marine food web. The ocean waters off New Jersey are nutrient-rich and very productive. The sea gets its deep-green color from countless millions of microscopic plants ( phytoplankton ) that thrive in the upper, lighted portion of the water column called the photic zone.

Phytoplankton provide food for zooplankton ( microscopic drifting animals ) and the larval forms of other marine animals, such as fish and crabs, that grow much larger as adults. Unlike plants, all animals must obtain their food through consumption and are thus called consumers. Animals feeding directly on plants are classified as primary consumers.

As this drifting, planktonic community of microscopic plants and animals is carried along by currents, it is also slowly sinking, eventually reaching the depths where reefs are found. At these depths - 50 to 125 ft - not enough sunlight may penetrate the water column to support photosynthesis. Thus, few plants can live and grow there and, as a result, very little primary productivity occurs on New Jersey reefs. Instead, these deepwater environments are colonized by marine animals - consumers.

Blood Sea Star ( Henrica sanguinolenta ) |  Common Sea Star: Forbes Asteria (Asterias forbesi) eating a Blue Mussel |

Gray Triggerfish (Balistes capriscus) |  Ivory Barnacles (Balanus eburneus) with Blue Mussels (Mytilus edulis) |

The Consumers

The initial input of energy ( food ) into the reef food web comes from two outside sources: phytoplankton drifting or carried by currents down from photic, surface waters, and detritus, which is composed of fine particles of decayed plant and other organic matter that washes from land out to sea. These two sources of energy, both derived from the primary productivity of photosynthesis, are captured by primary consumers on the reef - the filter-feeding animals that live attached to the reef structures.

These animals are known as fouling or encrusting growth or, scientifically, as epibenthos; they include blue mussels, barnacles, bryozoans, and sponges. These animals siphon seawater through their gills or guts, straining out plankton and microscopic food particles. They often carpet reef structures in dense colonies; for example, some surfaces support as many as 10,000 young mussels per square foot.

Other epibenthic organisms that also live attached to reef structures capture zooplankton and drifting larvae using small stinging cells. These animals are known as impingement feeders and include anemones, hydroids, and stony coral. Even the initial larval stages of higher forms of life, including fish, fall prey in vast numbers to the living, feeding carpet of epibenthos. Fouling organisms form the base of the reef food web, because they harness energy from the plankton in the water column, have a great collective biomass ( weight of organisms ) and become a source of food for higher-level consumers.

Once a fouling community is established on a shipwreck or other reef structure, a host of mobile invertebrates crawls in to dine on mussels and barnacles, which are anchored in place, unable to escape, their shells providing their only defense. Predators use an array of techniques to overcome the protective shells. Starfish employ hundreds of suction feet and hydraulic arms to pry open mussel shells - water pressure never tires; muscle tissue does. Jonah crabs and lobsters use powerful claws to crush the shells. Tautog, cunner, and Triggerfish have teeth designed for nipping off mussels, which are then swallowed whole.

Other sessile invertebrates are under attack as well. Sea Urchins crawl slowly over the reef, methodically grazing on minute invertebrate growth. Shrimp pick away at the soft, bulbous bodies of anemones. Animals that feed on primary consumers are termed secondary consumers. The carnage is so great that reef surfaces supporting dense colonies of mussels and barnacles in the spring are often cleaned bare by the fall. Only those fortunate enough to have settled in a tight crevice manage to survive. However, maintaining their status as the foundation of the reef food web, fouling organisms are prolific, and denuded reef surfaces are re-colonized annually.

Even waste products do not go to waste. The fecal matter expelled by the dense populations of the fouling community enriches the seafloor around the periphery of the reef. The fecal matter is reprocessed by filter- and deposit-feeding animals, called benthos, that live buried in the sand. These animals include tube worms, sand shrimp, nematodes, crabs, and sand dollars. Many of them thrive on the natural fertilizer shed by the reef community.

The Eaters Become the Eaten

Reef fish - Black Sea Bass, Tautog, cunner, Scup, and Triggerfish - forage on and off the reef. Mobile, epibenthic invertebrates living on the reef and the surrounding sand bottom - crabs, shrimps, amphipods, isopods, worms, and snails - are prime food items for reef fish. For example, crabs account for about 85 percent of the diet of Sea Bass. Some are captured around the reef; others are rooted out of the sand. The fish feeding on crabs are considered tertiary consumers. Being opportunists, Sea Bass will also attack schools of bait, such as Butterfish, Anchovies, or squid, that congregate around or swim by reefs.

Young-of-year fish, only an inch or two in length, that live on the reef are also subject to predation from other reef fish, such as Sea Raven and Conger Eel. Secluded hiding places within the structures may improve these fragile youngsters' chances of survival.

Wherever communities of marine life are concentrated, larger ocean predators will also congregate in hopes of finding an easy lunch. These predators follow either of two routes to the reef, over the sandy seafloor or through the water column. Those on the seafloor, called demersal predators, rely on stealth and camouflage to ambush unsuspecting reef denizens. Fluke and Monkfish, for example, are flattened fishes with skin that can alter its coloration to mimic the pebbles, shell fragments, and sand of the surrounding bottom, allowing these predators to practically disappear. They lie patiently in wait around the edges of reef structures and only strike when their unsuspecting victim approaches too closely for escape.

Those that visit from higher up in the water column are called pelagic predators. These constantly swimming predators, which include Bluefish, Striped Bass, Tuna, and sharks, rely on speed and agility to dart ahead and outrun their prey. The presence of reef structures makes this task a lot harder, and a relatively slow reef fish, which would otherwise be an easy target in the open water, becomes almost impossible to catch where reef hiding places abound. These off-reef marauders, when feeding on fish, represent fourth-level consumers.

( Charcharhinus plumbeus )

Each link in the food chain is called a trophic level. The trophic level assigned an animal depends upon the trophic levels of the food items it eats. Plants ( phytoplankton ) occupy trophic level 1; all the higher levels consist of animals. In the marine food web, most species feed upon a variety of items and, consequently, may fit in more than one trophic level.

With rare exceptions, people are at the top of any food chain and the reef food web is no exception. In 2000, recreational anglers caught 4.8 million fish of 25 species on New Jersey reefs. Scuba divers harvested 17,000 lobsters and 32 tons of mussels. These diverse seafood choices put humans in trophic levels 3 through 7 in relation to the marine reef food web.

Bill Figley is a principal fisheries biologist with

the New Jersey Division of Fish and Wildlife's Reef Program

Illustration by Barry F. Preim

Representative Animals Associated with a New Jersey Reef Food Web

| Reef Fouling Community | Sand Bottom Benthos | Mobile Reef Benthos | |

| Filter Feeders | Impingement Feeders | ||

Mussels Barnacles Slipper Shells Sponges Bryozoans Tube Worms Jingle Shells | Anemones Hydroids Stony Coral | Bloodworm Moon Snail Surf Clam Sand Worm Nematodes Sand Dollar Amphipods Razor Clam Lady Crab Rock Crab | Shrimps Crabs Isopods Amphipods Snails Sea Urchins Starfish |

2, 3 | 3 | 2, 3 | 3, 4 |

| Trophic Levels |

| Large Reef Predators | Off-Reef Predators | ||

| Invertebrates | Fish | Demersal | Pelagic |

Lobster Jonah Crab Spider Crab Rock Crab | Sea Bass Tautog Cunner Triggerfish Scup Sea Raven Conger Eel Red Hake Cod (in winter) | Fluke Monkfish Dogfish Skates Sea Robin Sandbar Shark Sand Tiger Shark Sculpin Rays | Bluefish Bonito Jack Tuna Sharks |

3, 4, 5 | 3, 4, 5 | 3, 4, 5, 6 | 3, 4, 5, 6 |

| Trophic Levels |

This article first appeared in New Jersey Outdoors - Summer 2002

A Close-Up View of Artificial Reef Life

By Herb Segars

A diver, escorted by a school of cunners, explores the bridge of the tug Spartan which was sunk on the Sea Girt Artificial Reef.

Blue Mussels anchor themselves firmly to structures with byssus threads. These threads can be severed if the mussel finds itself in an unsuitable environment, allowing it to crawl to a more favorable location.

A mixed colony of young mussels and Frilled Anemones feed actively on food brought to them by water currents. The mussels use siphons to draw in and filter food particles from the water, while anemones employ stinging cells to spear their tiny prey.

An asterid Sea Star feeds on a Blue Mussel. Sea Stars attach themselves to their prey with hundreds of tube feet and then pump their arms full of water, using hydraulic pressure to slowly open the mussel's shell.

Currents carry the Lion's Mane jellyfish over a reef. This is the largest jellyfish in the world and can cause an irritating sting.

The Sea Raven is a solitary , motionless hunter and voracious feeder that is capable of swallowing fish almost as large as itself. They may reach a length of two feet and a weight of seven pounds.

A juvenile Black Sea Bass. Sea Bass begin life as females, changing sex to males as they get larger.

The Black Sea Bass is one of the most abundant species on New Jersey's artificial reefs. Sea Bass feed primarily on crabs, shrimp, and other small crustaceans.

Winter Flounder spend the warm summer months in cool ocean water out to depths of 100 feet. They feed on worms, small crustaceans and clam siphons.

A colony of Frilled Anemones - animals that look like delicate undersea flowers.

A Sea Star crawls over a Red Beard sponge.

An Ocean Pout peers out of its new home, a sunken ship. Pout grow to three feet and a weight of 12 pounds.

A school of cunners swarms around a reef structure. A carpet of encrusting organisms, in this case dominated by hydroids, has covered the entire surface area.

The Spotfin Butterflyfish is a more common sight on the tropical coral reefs. Tropical species which have strayed northward occur on New Jersey's artificial reefs during late summer.

This nudibranch is a shell-less snail that feeds on hydroids. It transfers the stinging cells of the hydroid to the fronds on its back and thus protects itself from fish that try to eat it.

The beautiful Blood Star is a small sea star, usually less than two inches that feeds on sponges.

The hydroids growing on this tiny juvenile Spider Crab serve as camouflage, a disguise to fool predators.

A lobster guards the entrance to its lair, which it created by burrowing underneath a reef structure.

Eye to eyestalk with a lobster.

Sand Dollars are very abundant on the sandy ocean bottom. They feed on diatoms and micro-organisms in the bottom and are in turn fed upon by flounder and bluefish.

This article originally appeared in A Guide to Fishing & Diving New Jersey's Artificial Reefs - New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, 1989.