Eelgrass

Zostera marina

Size: to 36"

Seagrass: Nature's Nursery

Seagrasses are a group of approximately 50 species of vascular plants that complete their entire life cycle fully submerged in the marine environment. The most common and ecologically important seagrasses in New Jersey are eelgrass ( Zostera marina ) and widgeon grass ( Ruppia maritima ). Widgeon grass, however, is actually a fresh/brackish water plant with extreme salinity tolerance and is therefore sometimes not classified as a "true" marine seagrass.

Nevertheless, both eelgrass and widgeon grass are true flowering plants with subsurface roots and root-like rhizomes that extend through unconsolidated sediments varying from pure, firm sand to fine, soft muds. Seagrasses are found worldwide in shallow coastal waters and can migrate from year to year or even from season to season within suitable habitats. In New Jersey, they are most prevalent in the shallow ( <5' ) portions of the Navesink, Shrewsbury, Manasquan, and Metedeconk Rivers, and in Barnegat, Manahawkin, and Little Egg Harbor Bays.

Seagrasses are sometimes considered a nuisance by boaters and waterfront property owners where the vegetation can interfere with boat engines and tends to accumulate in piles of detritus on beaches. However, the ecological benefits provided by seagrasses can be shown to far outweigh any "inconveniences" to recreation or leisure.

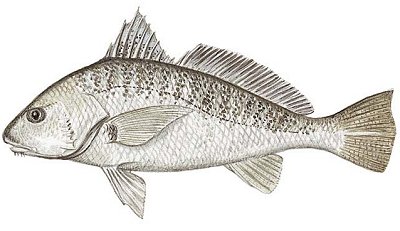

Specifically, seagrass communities help stabilize sediments, dampen wave energy, buffer shorelines from erosion and improve/enhance water clarity and quality. Seagrasses also serve an especially important role in the production of fishery resources. Extensive data indicate that seagrass meadows provide a high-quality habitat for fishes and invertebrates. For example, the physical structure provided by seagrass beds along with associated epiphytes ( attached algae ) and drift algae enhances the habitat for invertebrates by providing attachment sites and refuge from predators. In addition, the rhizome layer may protect shallow dwelling hard clams, whereas, on exposed sand flats, whelks and other predators easily detect and capture clams. Similarly, seagrasses serve as nursery areas for juvenile and subadult finfish, providing abundant and varied food resources as well as refuge and protection from larger predators. Many fishery organisms occur in seagrass beds at some stage in their life history, including juveniles of open water coastal fisheries ( menhaden, summer flounder, bluefish, Atlantic croaker, Pacific herring, spot, weakfish, silver perch, mullet, and blue crabs. )

While juvenile fish can utilize other types of shelter, the bulk of shelter habitat in many estuaries is provided by seagrasses. Its loss, therefore, will likely lead to declines in juvenile fish recruitment. Entire fisheries have completely crashed as a result of eelgrass loss. This was dramatically illustrated in the 1930s when a disease epidemic virtually eliminated eelgrass from the entire eastern US coastline. Scallops, clams, oysters, crabs, and many species of fish suffered dramatic declines from the loss of productive habitat with the concomitant siltation, creation of mudflats, and erosion that occurred because eelgrass no longer anchored bottom sediments.

While the catastrophic loss of eelgrass in the 1930s may have resulted from a very unique event, any activity that degrades seagrass habitat reduces light penetration or physically destroys seagrass will limit the plant's growth and survival. At the extreme, chronic levels of these disturbances could ultimately lead to the severe declines experienced in the 1930s.

Seagrass meadows are often subject to tremendous damage by even the most seemingly "innocent" human activities. For example, walking through seagrass meadows can drive shoots deep into the muddy bottom, which often kills them. More dramatic and systemic declines stem from decreased water clarity resulting from boat propeller wash and vessel wakes that can dislodge sediments and even uproot seagrasses. This is most commonly seen when vessels operate in or have wakes that reach shallow waters. The resuspension of sediments through turbulence generated by vessels can greatly reduce light penetration which in turn limits the distribution of suitable habitat for seagrasses.

Similarly, shading from docks and other structures also leads to seagrass loss. Light penetration and availability are thought to be the most important factors affecting and regulating the density, productivity, growth, and survival of seagrasses. In fact, reduction in the amount of light reaching seagrass blades is widely considered the major reason for seagrass decline in coastal waters.

Likewise, boat propeller scarring ( severing of seagrass leaves, roots, and/or rhizomes with a boat propeller ) resulting from boaters taking "shortcuts", misjudging water depths, or grounding are particularly destructive to seagrasses. Slow recovery ( up to 10 years or more ) from scarring, coupled with increased scarring rates, elevates the rate of cumulative loss of seagrasses and their habitat values.

Losses of seagrass due to chronic disturbances are difficult to reverse because the sediment stabilization and water column filtration benefits of the seagrass cover have been lost. Sediments are therefore easily re-suspended, adding to the turbidity of the water column and decreasing the likelihood of effective restoration.

Even if the affected areas resulting from any of these activities are relatively small compared to the size of the seagrass bed, these impacts fragment and disrupt the beds, making the entire habitat more susceptible to damage from other stresses like meteorological events such as storms. These and other disturbances may be acting together to result in large-scale declines in seagrass distribution.

Eelgrass is an important part of our coastal ecosystem and its health is an indicator of the overall health of bays and estuaries. The longevity of seagrass meadows, coupled with their complex physical structure and high rates of primary production, enable them to form the base of an abundant and diverse faunal community. For many fishery organisms, there is no one reason why they should be attracted to seagrass meadows, but rather there are a combination of features providing many essential resources. The benefits provided by seagrass systems are furnished free of charge, provided we act responsibly and protect this valuable resource.

References:

- Brown-Peterson, N.J. et al., 1993;

- Burdick, D.N. & F.T. Short, 1998;

- Fonseca, MS. et al., 1979;

- Fonseca, M.S., W J. Kenworthy & G.W. Thayer, 1992;

- Good, R.E. et al., 1978;

- Kenworthy, Wi. & D.E. Haunert (eds.), 1991;

- Lockwood, J.C., 1990; Lockwood, J.C., 1991;

- New Jersey Administrative Code Rules on Coastal Zone Management, 1994;

- Sargent, F.J. Ct al., 1995;

- Short, F.T., 1988;

- Stevenson, J.C & L.W. Stayer, 1990

This article first appeared in New Jersey Fish & Wildlife Digest - 2000 Marine edition